By Irma Walter, 2010

In 2010, a new bridge was constructed over the Collie River near its mouth. It is the fourth bridge constructed in this vicinity. The previous three bridges were constructed in 1848, 1911 and 1962. This story examines the history of the four bridges.

The Collie River is about 154 kms long and flows westward from its source in the Darling Ranges, ending in the Leschenault Inlet at Bunbury. It was named after Dr Alexander Collie, who was sent in 1829 by Governor Stirling on a voyage of exploration to the South West of WA. He was accompanied by Lieut. Preston and both had rivers named after them in the Leschenault catchment area.

The 2010 bridge stands at the border of three council districts, Harvey, Dardanup and Bunbury. It is located just to the west of the 1911 and 1962 bridges. The 1848 bridge was located several hundred metres further west of these where the Collie River enters the Leschenault Estuary.

Early History

The problems faced by early settlers in the South West of WA were huge, with transport and communications over vast distances being major issues. Shipping was the common form of transport for mail, freight and passengers, but this was restricted to coastal areas. With the opening up of land south of Perth and further inland, there was an urgent need for roads to allow for the transport of goods to ports and between settlements.

Due to lack of finance and an acute shortage of labour, the colony’s administrators were struggling to provide essential services to its scattered population. Settlers cleared their own narrow tracks through the bush but these were frequently made impassable by local conditions.

Mail contracts from Perth to Pinjarra, then from Pinjarra to Australind & Bunbury, by horse or by light spring cart, were being advertised in the Government Gazette as early as 23 January 1844. These mail contractors were frequently held up or forced to take lengthy detours back to the hills in order to bypass flooded rivers and boggy tracks. There was a desperate need for a more direct route south to service the settlements. Surveyors were faced with the prospect of pegging roads through some difficult terrain, with tall forests and several wide rivers such as the Murray, Collie, Brunswick, Preston and Blackwood Rivers.

Following the settlement of Australind in 1841, contact with Bunbury was not easy. The first bridge in the area was built over the Brunswick River in 1845 by William Forrest. However, it did not meet the needs of those in the Australind townsite and land-holders closer to the coast, who wanted a more direct route to Bunbury. Goods and passengers were either being ferried across the river, or travellers took their carts out past the mouth of the river and into the estuary in order to get across, a dangerous tactic which led to some accidents and even drownings, with crossings only possible at low tides.

First Collie River Bridge, 1848

In July 1848, a motion was put in the WA Legislative Council for £150 to be spent on the construction of a bridge near the mouth of the Collie River. Comments made at the time suggested that the only use for such a bridge would be to accommodate the postman and also the Commissioner of the Western Australian Company (MW Clifton), on his twice yearly trips to Perth. The Hon. S Moore commented that it was a worry that Clifton saw Bunbury as the future seat of Government in WA. The motion was rejected due to the impoverished state of the colony’s finances and the greater need at that time for a bridge over the Swan River at Fremantle.[1]

However an agreement was reached shortly after that a bridge would be built with joint contributions from the Government and local settlers. W Pearce Clifton was put in charge of construction and locals were to provide the labour. By October 1848, a large team of workers had fifteen piles already in place, some up to 30 feet in length, each driven in by upwards of a hundred blows to a heavy ‘monkey’.[2]

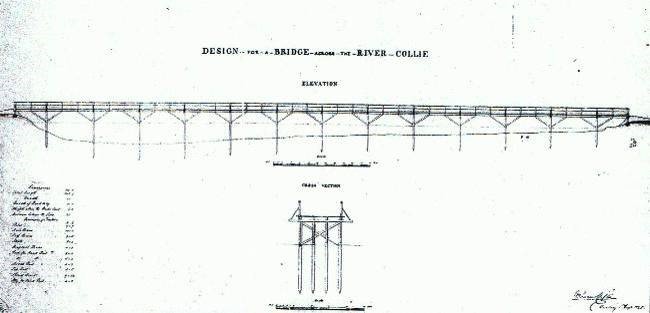

Collie River Bridge, drawn by W Pearce Clifton, 1 August 1848.[3]

Clifton and his brothers were already operating a saw-mill at his Alverstoke property, which may have been the source of the timber necessary for the construction work. However, since this farm was some miles from the chosen site, which would have caused transport problems, it may have been more convenient to source and mill the timber closer to the site. The timber was pit-sawn. Clifton’s simple drawing shows a bridge that was 345 feet 9inches long and 12 feet wide with 13 piers consisting of 4 piles each, with struts reinforcing the piers.

Clifton chose to use 9 feet x 9 feet sawn timber in preference to round piles, an unusual choice at the time. A letter which may explain this decision was written by WD Higman, Commissioner of Roads, to the editor of the West Australian newspaper in 1880, recognising Clifton as having more experience with jarrah than any other colonist. He asserted that Clifton held strong views about the virtues of hewn timber over round piles, due to the damage caused by the marine pest Toredo beetle to the outer white layer of jarrah, while leaving the solid inner wood relatively untouched.[4]

No time was wasted in getting construction underway, with the Governor reporting to the Legislative Council in April 1849 that the bridge had been completed and was a credit to the constructor, W. Pearce Clifton, who went on to build other bridges in the district. The bridge cost a total of £350, with £50 of this amount being contributed by the locals.

The 1848 bridge (1911 bridge in the background).

We must admire the efforts of this team of amateur bridge builders in assembling this large structure in difficult circumstances, using traditional methods and minimal equipment of timber pile frames, broad-axes and adzes. They used a horse-works on the bank and long ropes to raise the heavy weight, or ‘monkey’, in the pile frame in order to drive in the piles, or otherwise simply manpower.

The bridge enhanced the lives of the local population, allowing greater social interaction between families on isolated farms, as well as reducing the journey from Australind to Bunbury from twelve to seven miles.

The site chosen was much closer to the river mouth than the current (2010) bridge and presented problems for the road approaches on either side of the bridge, due to the low-lying nature of the area. Regular flooding of the flats did not help matters. The provision of convict labour a few years later helped with road improvements, with a gang reportedly sent there in 1852.[5] The approaches to this bridge can still be seen today on either side of the river, close to the canal walk-bridge nearest to the river mouth.

With the collapse of the WA Company in 1844 many disillusioned families moved away from the Australind area, and the remaining settlers struggled to survive. However, as far back as 1882 it was obvious that the ageing bridge structure was inadequate. A newspaper article in that year stated that neglect of the Lower Collie Bridge could cause a catastrophe, due to the continuous heavy loads of timber being carted to saw-mills. The local Roads Board declared it to be dangerous.[6] Tenders were called in 1905 for bridge repairs costing approximately £246.[7]

Although a second bridge was built in 1911, the 1848 bridge remained in position for a number of years after that for recreational purposes and also served as a foot-bridge. The middle section was raised to allow yachts to sail below. Pedestrians had to take steps up over this raised section.

The modified 1848 bridge.

During World War 2, a fear of Japanese invasion led to army recruits being given practice in using explosives by demolishing the bridge. Remaining piles were a bane to small boat owners using the river. According to local resident Judy Johnston, local children used to dive off the piles near the bank when swimming. In 1958-59 local earth-moving company Caruso Co. was sub-contracted by JO Cluff to lift the piles out of the river bed.

Retired Main Roads bridge builder Noel Miles recalls that his gang was given the task of removing the remains of these piles around 1967, as boat owners constantly complained about them being a hazard. The piles were below water level and it was a difficult job getting them free, using heavy ropes and an International TD18 bulldozer on the bank. They dived in from a boat to attach the ropes around the base of the piles. To their surprise, when raised, they found that the base of the timber piles were encased in bales of wool. How amazing that the wool was still in place nearly a hundred years later!

(Further investigation via the internet confirms that there were instances of this method being used by some bridge builders in Britain as a means of controlling the flow of the river and stablising the muddy bottom during construction. Wikipedia, however, dismisses as legend that London Bridge was built on wool.[8])

Second Collie River Bridge, 1911

The second bridge over the Collie River was built 300-400 metres up-river from Pearce Clifton’s original 1848 bridge, which was still standing at the time, but by then was mainly used for crabbing & fishing. (In 2010 the abutments or approaches to the 1911 bridge could still be seen a few metres up-river from the current bridge and the remains of its narrow approach roads could still be seen in the vicinity of the recreation area at Pratt Road in Eaton, next to the 1962 bridge.)

Towards the end of November 1911 a deputation from the Harvey Roads Board approached the Minister for Works for assistance in completing the new bridge. Chairman Mr R Driver pointed out that although the new bridge had been completed for some time, settlers continued to use the dangerous old bridge, because the Board did not have the necessary funds (£200) to form the approach on the Harvey side. He also pointed out that the Harvey Roads Board had 600 miles of roads in the district, more than any other Board in the South West, and was struggling to maintain these. The Minister gave them a sympathetic hearing, while at the same time stating that he believed that there had been an understanding that the Board was to complete the work. He appreciated that, as the Board had built the bridge, it was important that it should be used, so their request would be considered.[9]

This second bridge, built in1911, was a single lane structure, requiring users to give way to vehicles approaching from the other direction. The bridge was higher than the previous one and had a fishing platform below. Main Roads describe it as 379 feet total length (2/18’ and 3/20’ spans.) 14’.0” B/K. STS DP (PWD 15460).[10] Cost approx. £1561.

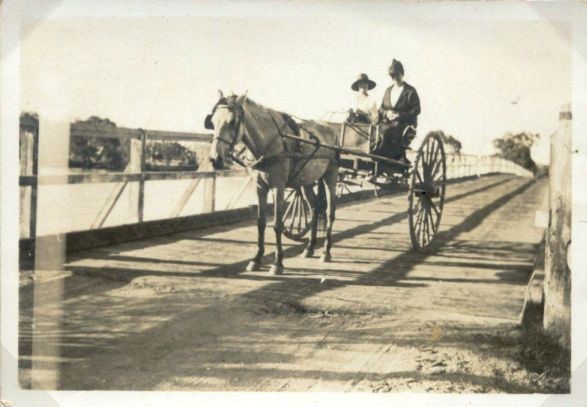

Julia Catherine Bartlett & daughter on Collie River Bridge.

Photo courtesy of Bartlett family.

In later years people recalled being nervous when crossing the structure, as it became necessary for them to keep their wheels on two rows of planks, which had been placed over the decking as reinforcement in 1946. Occasional flooding was also a problem.

This bridge continued to be used until 1962, despite many letters of complaint from the Australind Progress Association and others, declaring that it was particularly unsafe for children on the school bus. Signs limiting the weight load to 7½ tons were erected, but complaints continued that weight and speed limits of 10 miles per hour were being ignored. It was not until pressure was put on the Harvey Council and the State Government by the developers of the Laporte Industries processing plant in Australind that a decision was finally made to replace it. Urgent repairs to the approaches and handrails were carried out in 1962, not long before it was replaced.[11]

Collie River and 1911 bridge, looking towards Australind from the Eaton side, 1950s.

Photo courtesy of Mike Reeve.

Boating, fishing, crabbing and picnicking were very popular activities in the early twentieth century. Catering for these needs was the Taylor tea-rooms and boat-hire, situated about half-way between the first and second bridges, and accessed by boat from Bunbury or via Taylor Road on the Bunbury side of the river.

Third Collie River Bridge, 1962

Plans were drawn for the new bridge, just a few metres down-river from the previous one. The plan shows 18 navigation piers six piles wide, with a wider steel navigation span at the middle. The bridge was to be a two-lane timber structure, 14 feet wide. Ladders led down to two fishing platforms below and a pedestrian path was provided at the side of the bridge.

It had timber piles, which were driven in by a timber pile frame – a version of this frame is presently displayed outside the Main Roads Office in Bunbury. The road level of this bridge was about the height of the top of the handrails on the previous bridge.[12]

A contract for the bridge construction was let at £32,851, plus approaches £15,000 and fishing stages £2,000. Delays were caused when the first tenderer was unable to proceed, so tenders had to be re-called.

Laporte Industries was unable to use the old bridge to get the building materials to its construction site in Australind. A question was asked in Parliament over the delays and pressure to get the new bridge completed resulted in an expert team of timber squarers being sent to assist with the work.[13]

Mr AF Ball, the second contractor, agreed to allow limited passage of traffic through as soon as the decking was laid. Noel Miles stated that the 1911 bridge would have been removed by the contractors before the approaches to the new bridge could be constructed, as the wings (abutments) of the old bridge would have been in the way.

In August 1962 the Australind Progress Association put forward a proposal that the new bridge should be named the ‘Australind Bridge’ rather than the ‘Collie Bridge’, as there were several other bridges by that name. This was considered by the Nomenclature Committee of the Lands and Survey Department and was officially adopted in 1962. It is recorded as being built near an aboriginal site known as Borrigup. However, due to common usage, the name has reverted back to the ‘Collie Bridge’.

During Easter of 1971, over 26,000 vehicles were recorded on the Old Coast Road, about the same number as used the South Western Highway. Concern over the amount of traffic coming through Australind led to a deputation from the Harvey Shire to the Minister for Works in 1972, proposing that the Old Coast Road should be gazetted as a Main Road, with responsibility for its maintenance taken over by the Main Roads Department (MRD). A compromise was reached when the MRD agreed to carry out upgrades worth $3,000 to the Australind Bridge in 1972.[14] In 1985 the bridge piles were found to be in a poor state. Tenders were called for fibreglass protection jackets to be put around the piles, with the space between being filled with bitumen.[15] In 2002 traffic was severely disrupted when the bridge piles were further upgraded. In January 2004 the Shires of Harvey and Dardanup applied for $4.5 million in MRD funding for a replacement bridge.[16]

The removal of the old bridge and refurbishment of the boardwalk was undertaken by Bocol Constructions Pty Ltd of Perth.

Demolishing the third bridge.

Photo courtesy of Bocol Constructions Pty Ltd.

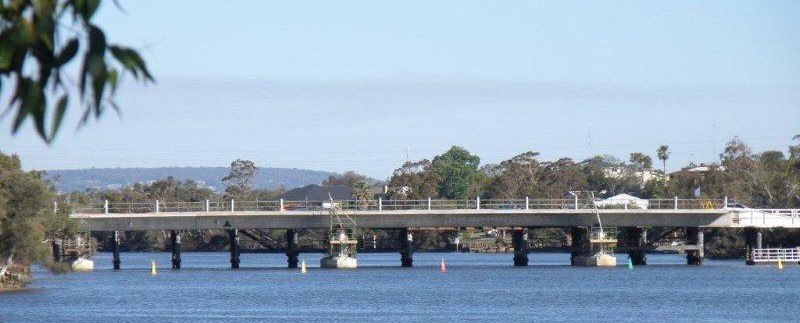

Fourth Collie River Bridge, 2010

Construction of the new concrete and steel bridge commenced in January 2009, with Macmahon Contractors winning the contract. The bridge is 121 metres long and 13 metres wide, with two 3.5 metre traffic lanes and a separate dual-use cycle and pedestrian path. The bridge was officially opened on 15 April 2010 by the Minister for Transport, Simon O’Brien.

Just before the bridge opening, Main Roads WA contracts manager Scott McKay stated that the old 1962 bridge had served the community well, but unfortunately a combination of salt water and borers had contributed to a shorter life span than similar bridges inland. When dismantled, it was intended that some of the salvaged timbers will be used to repair other bridges in the South West. The bridge fishing platform would be refurbished, but it was not intended to re-align the existing footpath.[17]

2010 Bridge during construction.

[1] Perth Gazette & Independent Journal of Politics, 29 July 1848.

[2] Inquirer, 11 October 1848.

[3] JSH Le Page, Building a State: The Story of the Public Works Department of Western Australia 1829-1985, Water Authority of WA, Leederville, 1986, p. 49.

[4] West Australian, 27 January 1880.

[5] Perth Gazette, 5 March 1852.

[6] West Australian, 3 March 1882.

[7] Contract 2487.

[8] Blackwell Bridge Darlington, http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/history/blog/9741649

[9] West Australian, 25 November 1911.

[10] PWD Standard Drawing: 12804-7-9.

[11] PWD plan 15460, 26 June, 1962.

[12] West Australian, 26 July, 1962.

[13] MRD correspondence, 1 August 1962.

[14] Letter to Harvey Shire Council, 16 May, 1972, M.R.D. 316/72.

[15] Main Roads, Drawing Number 8530-0500-1.

[16] ABC News, 5 January 2004.

[17] Bunbury Herald, March 23, 2010.