Joseph Gray was born in Durham, Stockton in 1823, to parents Thomas Gray and Ann Daniel. He married Elizabeth Sarah Money on 2 July 1848 at the Clerkenwell Church in Finsbury, London. Joseph was recorded as a tool dealer and Elizabeth, who came from a respectable family, as the daughter of James Charles Money, a beedle. [Beadle: a minor Parish official.[1]] The couple both signed their marriage certificate.

At the time of the 1851 Census they were living at 47 Clerkenwell Green, in Finsbury, Middlesex – Joseph aged 27, Elizabeth 27, and their son Joseph, aged 2.

Joseph Gray was considered to be a respectable married man who ran a watch-makers’ and jewellers’ tool-making business in Clerkenwell, in the heart of London. In 1855 neighbours were surprised when police arrived at the scene, asking questions about stolen watches. It wasn’t until Joseph was confronted by a witness that he admitted having recently bought some of the watches over the counter. Following further investigation, he was indicted at the Central Criminal Court for receiving nine gold watches valued at £100, nine watch cases worth £50, and several other items, the property of William Langford, knowing at the time that they were stolen goods. It appears that he was involved in what was a common practice at the time, of ‘re-christening’ watches, that is, erasing the names of the maker or the owner to remove their identity before re-selling them. Despite a number of witnesses being called to give Joseph Gray a good character reference, he was found guilty and ordered to be transported for 14 years.[2]

His Term in Western Australia

Joseph Gray arrived at Fremantle on 3 July 1857 onboard the Clara (Journey 1). On arrival he was described as a 34-year-old dealer, with dark brown hair, grey eyes, an oval face, a dark complexion and middling stout in build. He had a caste in his left eye. He was married, with four children.[3]

Joseph seems to have kept a low profile in the Colony, with a minor offence registered against him –

No. 4283 – Joseph Gray, 32, dealer, married, 4 chn, reads & writes well, good character, on 30 Oct. 1861, convicted of being out after hours. Length of Sentence – at His Excellency’s pleasure.[4]

He received his Ticket of Leave on 2 February 1859 and his Conditional Pardon on 4 April 1861.[5] Like many others before him, Joseph left the Colony at his first opportunity. He was determined to get back to his family in England, despite being aware that although regulations allowed him some freedom of movement, they prevented him from returning to his homeland before his full term of transportation had expired.

Back in England

By 1863 he was back in Middlesex, ostensibly re-united with his wife and family, and again carrying on business as a watch and tool maker and dealer at No. 47 Clerkenwell Green. In 1869 he was arrested and charged with being unlawfully at large, in violation of the terms of the Conditional Pardon given him in 1861 by returning to England in 1863. He claimed at the time of his arrest that the local police had been well aware of his return for several years, but had previously taken no action against him.

On 1 April 1869, facing trial in the Central Criminal Court, Joseph Gray admitted the crime and was sentenced to a further seven years’ term of penal servitude in England, since the practice of sending convicts to Western Australia had ceased in 1868.

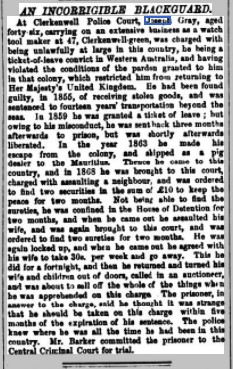

The English press had taken an interest in the case, revealing extra details of Joseph Gray’s conduct after his return –

North Devon Gazette, 9 February 1869.

A few months later, news of his conviction had reached Western Australia and was reported in a Perth newspaper –

RETURNING FROM TRANSPORTATION – In the Central Criminal Court on April 1, Joseph Gray, pleaded guilty to being at large before the expiration of a sentence of transportation to which he had been subjected. The prisoner, who had been in a business as a silversmith on Clerkenwell-green, was convicted in 1855 of receiving stolen goods, and sentenced to 14 years’ penal servitude. In March 1857, he was transported to Western Australia, and in 1862 he received a conditional pardon, the condition being that he was not to return to the United Kingdom during the unexpired part of his sentence of transportation. He was seen in London in December, 1863, and since that time had been repeatedly convicted summarily of minor offences. He was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude.[6]

Yet more details were to be revealed concerning Joseph Gray’s arrest. Trouble had been brewing on the home-front ever since his arrival back from Western Australia. The following article tells a rare and surprising tale of a wife asserting her rights, at a time when women were considered as chattels of their husbands, and their property rights were few –

Finsbury Free Press, 6 March 1869

Not only did Elizabeth Gray report her husband for escaping from Western Australia and returning to England. Tired of his drunkenness and his violent behaviour towards her, and no doubt fearful for the safety of her children, she had applied for a divorce from her husband in late 1868.

By this time she had born six children, four girls and two boys. The grounds for the divorce was cruelty, with many instances outlined by her solicitor. On two occasions her husband had forced her and the children out onto the street. When a neighbour came to Mrs Gray’s rescue on the second occasion, Joseph violently assaulted him and was himself taken into custody. Elizabeth Gray stated that she had not lived with her husband from that time. The divorce was granted on 4 June 1869 on the grounds of cruelty.[7] [Although a new law had been passed in 1857, permitting ordinary people to be granted divorce on certain grounds, it was still a rare occurance at that time. (See Appendix.) ]

Saved from transportation back to Western Australia, Joseph Gray at first spent time at Newgate Prison, where he was employed as a ‘picker’. [Most likely picking oakum, which involved pulling apart old rope, to be used for plugging gaps in the decks of ships.] On 31 March 1869 he was transferred to Pentonville, where he was placed in Separate Confinement, this time employed as a tailor. In their records his physical description was described as sallow, with dark brown hair, height 5’7”, a scar on his temple and nose, and a mark on his right arm. He could read and write well. His family contact was EJ Gray of Endbury Villas, Chingford, Essex. He was permitted to send a letter on 25 February 1870, and received one on 5 March that year.[8]

Joseph also spent time in Chatham Prison from 22 March 1870, before being sent to Gillingham Prison in Kent, where he was listed as a prisoner in the 1871 Census. On 4 September 1874 he was sent from a convict hulk to the Borstal Prison site, as one of the prisoners sent there to complete its construction. He was released on Licence in April 1875.[9]

At the time of the 1881 Census, Joseph Gray, 58, tool dealer, was living at his former address, at 47 Clerkenwell Green in Finsbury, along with a housekeeper and a servant (shopman).

Ten years later he was listed in the 1891 Census as a retired tool merchant, aged 68, living alone at the same address.

The date of Joseph Gray’s death is unknown.

………………………………………………………….

Further details of his wife, Elizabeth Sara Gray

At the time of the 1871 Census, while Joseph was in gaol, Joseph’s former wife Elizabeth Gray, aged 47, was still running the family business at 47 Clerkenwell Green as a tool dealer, living with her son Joseph (19), and her daughters Sophia (19) and Annie (3).

In the 1881 Census, Elizabeth was living at 18 Wilberforce Road in Finsbury with her son Joseph, a tool manufacturer, her daughter Margaret (17) and her sister Sophia Money, aged 54.

On Christmas Day 1895, Elizabeth Gray, of 31 Gloucester Road, Brownswood Park, Middlesex, passed away. Probate details in June, which described her as ‘wife of Joseph Gray’, shows her effects to the value of £571 15s. 6d., left to Joseph Gray, dealer in watchmakers’ and jewellers’ tools.[10]

It is hoped that this beneficiary was her son Joseph, not her former husband.

…………………………………………………………

Appendix

1857 Matrimonial Causes Act.

This act allowed ordinary people to divorce. Before this, divorce was only available to men and had to be granted by Parliament which was a hugely expensive process. Under this law, women divorcing on the grounds of adultery had to prove this to the courts and prove additional faults like domestic cruelty, rape and incest.

This law remained unchanged until 1937 where divorce became allowed on the grounds of drunkenness, insanity and desertion. (https://www.hawleyandrodgers.com/brief-history-of-divorce-law-in-the-uk)

……………………………………………

[1] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/beadle

[2] Morning Advertiser, 5 July 1855.

[3] Convict Department Estimates and Convict Lists (128/1-2)

[4] Convict Department Registers (128/38-39)

[5] Fremantle Prison Convict Database, fremantleprison.com.au

[6] Inquirer, 14 July 1869.

[7] UK National Archives, England and Wales , Civil Divorce Records. 1858-1916.

[8] UK National Archives, Home Office Prison Commission: Male Licences, Series PCOM3, Piece No. 400.

[9] Ibid.

[10] England & Wales, National Probate Calendar, (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1896, Eade-Gyton.