By Irma Walter and Heather Wade, 2017.

For many years the Fielder name was closely associated with the fruit-growing industry in Western Australia. As young men, the Fielder brothers, Charles Horace, Daniel George, Thomas Victor and Arthur Gordon Fielder were all employed in Jacob Hawter’s Harvey Citrus Nursery, as part of the workforce kept busy raising stock to satisfy the demands of new landowners. The two oldest brothers then went on to establish their own nurseries, and for a time a third generation of Fielders followed this tradition.

[The first nursery in Harvey was set up by Jacob Hawter in 1903, as an adjunct to his well-established Mullalyup Nursery, to better service the fledgling citrus industry in the district. He chose 22 acres of land near the railway station, in order to facilitate the rapid servicing of orders for his customers. The nursery employed many locals and became the training ground for many nurserymen, some of whom went on to run their own nurseries, while others established their own orchards and farms. Managers included AE Stanford, Thomas Henry Latch and Daniel George Fielder. Following the death of Jacob Hawter in 1926, the Hawter Nurseries were run for several years by his son Kenneth, probably up until the time of his enlistment during WW2. Ken Hawter lost his life in Borneo in 1945. The Harvey Citrus Nursery land was sold and is now the site of the Harvey Hospital, the town’s tennis courts and bowling club, as well as the school oval.]

Charles Hamilton Fielder

The Fielder family’s connection to WA began with the 1905 arrival on the SS Afric at Albany, of Charles Hamilton Fielder (b.1883) and his wife Ellen (née Wooders, b.1883), and infant son Charles Horace (b.1905), who was christened at sea. They came from Croydon in Surrey, where Charles had been employed as a farmer.[1] His father Edward was a Brewer’s Agent in Croydon, Surrey.

Charles Hamilton Fielder arrived in WA at a time when vast areas of land were being opened up to immigrants arriving from Britain. He earned a living working for the Government clearing virgin land for farmers, commencing in the Denmark area, then working around Armadale and Harvey, where the team used steam-powered tree-pulling equipment.

Charles Hamilton enlisted in the First World War in 1916, describing himself as a bushman, with his wife Ellen recorded as his next-of-kin, a resident of Armadale near Perth. Charles was wounded in action in France in 1917, suffering a gun-shot wound to his right arm. He was promoted to the rank of Corporal in 1918 but was wounded in his left elbow in April that year and was evacuated to England. He rejoined his unit in October 1918 and arrived back in Australia in January 1919.

Charles Hamilton Fielder and wife Ellen, WW1.

The family settled in Harvey, where Charles Hamilton Fielder was initially allocated two leasehold blocks as a Returned Soldier. He raised his family there, doing occasional work outside the property to help make ends meet. The Government employed some of the settlers in land clearing and drainage work. According to Staples, the Fielder blocks were part of the Plains Paddock subdivision.[2] This is confirmed in the Harvey Roads Board Rates Book for 1922, with Charles listed as the owner of two blocks, Sections 134 -136, 144 and 146, with an area of 63 and 64 acres. By 1930 his holdings had increased to No’s 134-138, 142-144, and 146, with acreages of 127 and 67 in total.[3] Situated off Yamballup Avenue on a hillside overlooking the river, the property was named ‘Bridgeview’.

Harvey was seen by the Government as suitable for a ‘Close Settlement’ development and was one of the first areas chosen for soldier settlement after WW1. Blocks from the Korijekup sub-division that had not been taken up by citrus growers were allocated for this purpose. Other areas were opened up in the Plains Paddock, Uduc and Greenpools areas around Harvey. Many of the blocks proved unviable because of their size.

There was some Government assistance provided, such as offering training sessions for the more than 100 men who took up the offer of land in the area, but they faced many ongoing difficulties. Complaints about the state of roads in the district were numerous, and poor drainage led to some areas being only accessible on foot in the winter, thereby making it almost impossible for those farmers to get their produce to market. When writing his book on the history of Harvey, AC Staples interviewed some of the descendants of these soldier settlers, who spoke of the ‘unremitting toil of fathers, mothers and children for meagre returns from badly drained soil, cleared at great expense, even when some of the physical effort was supplied by tree-pulling tractors’.[4]

Some of Fielder’s neighbours from the Plains Paddock area were part of a deputation who went to the Harvey Roads Board with their complaints:

A deputation from the Harvey branch of the R.S.L., consisting of Messrs C. L. Spurge, H. Blowfield, and Chard, waited on the Board with a view to ascertaining what steps were going to be taken to put the roads in order. Mr. Spurge pointed out that a good road would be very hard to find around Harvey. In one instance, he said, a returned soldier settler was carting fencing wire on a sledge down Ninth Street and floating it across the river to his block.

Mr. Blowfield spoke of the condition of Third Street. He said that it was impossible even to take a light load down the road. Mr. J. Stewart mentioned that the Government had allotted £506 for Third Street and Plain Paddock. Mr. Blowfield— £500 won’t take it to Chard’s place. Mr. Chard pointed out the trouble he had had to get a bridge over the river at Third Street. He thought that £500 was not enough for the Plain Paddock Road.

Mr. Spurge suggested a deputation to the Premier and the Minister for Works with a view to obtaining a substantial loan to make the roads. It was moved that a deputation of three R.S.L. members and one Roads Board member wait on the Minister for Works.

Many of the blocks changed hands as recipients found themselves overwhelmed by increasing debt. Bridges which were built over the Harvey River at Third Street in 1920 and another at the east end of Yamballup Avenue in 1924 went some way to easing the access problems faced by Charles Fielder and his neighbours:

The Public Works Department have had a gang of men at work on repairing the Third Street bridge which had become unsafe owing to the action of the water undermining the approaches; this work is about complete. The party will now be transferred to a new job higher up, where a bridge is to be erected across the river at the east end of Yambalup Avenue, thus giving direct communication between that area of Soldier Settlement known as the Plain Paddock and Korijekup. This has been a long looked for bridge as it will mean the saving of time and money to all the settlers on the Plain Paddock.[5]

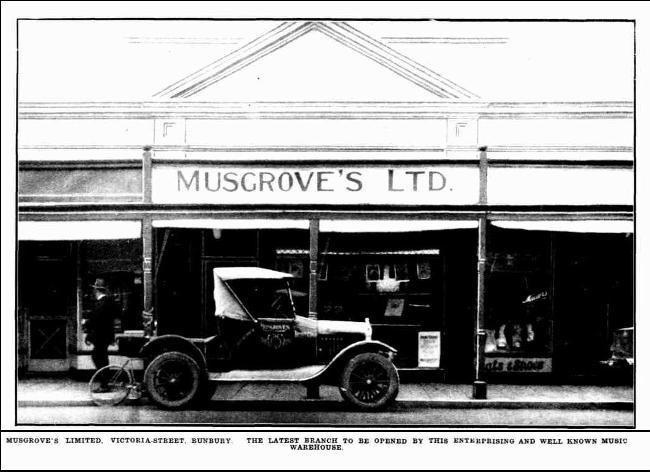

For a number of years Charles milked cows and raised livestock. He bought a truck to take his milk to the factory, collecting cans from other producers on the way.[6] However, like many others, Charles Hamilton Fielder lost his farm in the 1930s, due to mounting debts. The last time his name was recorded in the Harvey Rates Books was 1938, though by this time Charles was already working elsewhere. He had found employment with Musgroves, a firm which had opened a music store in Victoria Street in Bunbury. An advertisement in 1936 listed Charles as their Harvey agent.[7] The firm was an early player in the field of wireless, having conducted WA’s first commercial broadcasting station from its Murray Street premises in Perth between 1930 and 1943.[8]

Musgrove’s Bunbury Store in Victoria Street, 1927.[9]

Wireless reception was poor in the Bunbury area up until 1933, when Station 6BY opened, resulting in increased sales of wireless sets. Musgroves, sole WA agents for Stromberg-Carlson consoles, provided Charles with a Bedford utility, in which he travelled each day to Bunbury and around the district, selling and servicing wirelesses. He erected a tall aerial on a wooden frame to improve his wireless reception at his rented house in Harvey. His daughter Jean, a talented pianist, also worked for Musgroves, where she demonstrated pianos for prospective buyers.

The family later moved to Bunbury, recorded as living at 62 Stirling Street from 1944 to 1947, before moving to Spencer Street.[10] Charles and Ellen spent their later years in Bayswater, where they lived not far from the nursery of their son Dan Fielder.

Ellen’s death occurred in 1954 and Charles Hamilton Fielder lived on for many more years, passing away at the age of 87 in 1970. Both Charles and his wife Ellen were interred at the Guildford Cemetery. Their only daughter Jean took good care of both parents in their old age, remaining single until 1971, when she became the second wife of widower Ronald Albert Newbey.

The Next Generation

In the years following the Fielder family’s arrival with baby Charles Horace in WA in 1905, eight more children were born. Two children, John and Lewis, died as infants. The surviving children were Charles Horace (born England 1905), Robert (b. Denmark WA 1906), Daniel (b. Denmark 1910) and Thomas (b. Katanning 1913), Arthur (b. Armadale 1915), followed by Jean (b.1920) and Frederick (b.1923), both born at Harvey.

The boys of the Fielder family knew the meaning of hard work, leaving school at the age of 14 to find employment in the Harvey area. In 1919 the eldest son Charles Horace left school and was offered a position at the Hawter Citrus Nursery, which at that time was being managed by Thomas Latch. His brother Daniel Fielder was also employed there. Owner Jacob Hawter was based at his larger property ‘Hawterville’ at Mullalyup, but travelled to Harvey regularly to check on the workings of the citrus nursery. He was considered a fair boss who expected loyalty and hard work from his workers

Daniel George Fielder

By 1933 Daniel Fielder was manager of the Harvey Citrus Nursery, speaking knowledgeably about various aspects of the industry when interviewed by the South West Advertiser. He said that though the initial surge in citrus planting was past its peak, it was estimated that 7000 citrus trees would be sold that year from the Harvey nursery. The article tells us that 16 acres of land were being used for nursery purposes and gives an indication of the wide range of stock on offer that year –

At the Harvey nursery particular attention is given to the cultivation of trees of the deciduous variety. Enormous quantities of these trees are sent from the nursery annually. Plums are in greatest demand and no less than 6000 trees are on an average railed to all parts of the State yearly. Of the others the output is as follows: apricots 3500; peaches 3003; nectarines 1600; almonds 1500. The plums are grown from cuttings on the Myrobolan plum stock. Peaches, nectarines and almonds are worked on peach seedlings, whilst the apricots on apricot seedlings.

Hawter’s nursery claims the distinction of having introduced two rare varieties in Goldmine and Dr. Chisholm to the nectarine variety. Since their introduction some 20 years ago, the cultivation of this delicious fruit has been given a great impetus. Louquats are still in keen demand and last year no less than 1300 trees were supplied. The loquat is worked on loquat and quince stock to suit variation in soil.

Particular attention has been given to the cultivation of the rose and no less than 300 varieties are included in the collection at the nursery. The demand annually totals approximately 2000, which find their way into gardens in all parts of the State. All roses are worked on to briar stock and new varieties are being added to stocks as soon as they are catalogued in other parts.[11]

During the interview Dan Fielder expressed a special interest in the propagation of camellias, indicating with pride the avenue of trees along the boundary, planted some 25 years earlier, which in season displayed a mass of richly coloured blooms.

Dan was still employed at Hawter’s nursery in 1937, when he gave evidence in court against a person who had presented a valueless cheque.[12] In the mid-1930s he was a drummer in the popular local band known as the Harvey-Waroona Merrymakers.[13]

Dan Fielder, drummer, and the ‘Merrymakers’.

Dan probably worked for Hawter up until the time of his enlistment in the army in 1942. In 1944 his wife gave birth to a son Ronald in Perth. Following his discharge in 1945, Dan set up his own nursery in Bayswater and in 1949 was advertising the sale of currant and sultana vines from his nursery in Benara Road, Bayswater.[14] His nephew Malcolm Fielder remembers Dan playing the drums for dances at the Unity Theatre in Beaufort St, Perth.

Charles Horace Fielder

From 1919 Charles Horace was taught all aspects of plant propagation at Hawter’s Nursery, before looking elsewhere for better paid jobs. In 1927 he was an employee of the River Board, when it was reported that he was off work due to injuring his heel badly when starting his motor bike.[15] In 1929, while employed in the orchard of GH Charman, he successfully sued his employer for medical costs incurred when he acquired an injury as a result of lifting heavy potato bags.[16] He also worked for a six-month period at Snell’s property setting up a mandarin orchard, before re-applying for a position at Hawter’s Citrus Nursery, where he worked up until its closure sometime prior to WW2.

Following Charles Horace’s marriage to Millicent (‘Maisie’) Wright in 1930, the family lived for a time in the manager’s house on the Hawter property. Their first child was Norrie Charles (b.1931), followed by Malcolm born in 1932, but two years later the family was asked to move out of the house to make way for the manager, Charles Horace’s brother Daniel Fielder, who had married Dorothy Symmons in 1934. Charles Horace’s family then went to live in Knowles Street.

Around 1944 Charles Horace decided to set up his own nursery in Harvey and with the assistance of his sons he began clearing a block infested with bamboo next to his house in Knowles Street. He commenced his own nursery there, before moving to Fryer Road, where he grew roses and fruit trees to supply Dawson’s Nursery in Perth. He extended his land holdings to blocks in Herbert and Hocart Roads, where he employed locals, such as Charles Berry and Bert Prince. Other employees included one Estonian, Herman Warra and nine Italian immigrants, whose names included Cosmo and Tony Chiera, Joe Calabrio, Joe Panico and Nunciato Alexandrio, who all proved to be steady workers. Finding it difficult to obtain staff in the 1950s, Charles Horace sponsored two migrant Dutchmen, Jan Mertens and Jan (‘John’) Germs, the latter becoming the husband of Norma, one of the Fielder girls, in 1955. Another long-term worker was Dorothy Robinson, employed in Charles Horace’s office for 32 years. At one stage he also employed Tom Latch, an old friend from the Hawter Nursery days, who came out of retirement and approached him at the age of 65 for work in the trade that he knew so well.

Len Taylor loading Fielder’s fruit trees at Harvey station.

When rival nurseryman John Hepton decided to sell his small nursery in Uduc Road in 1952 Charles Horace bought him out. This property was later sold to Harry Baker.[17]

Over several years Charles’s brother Dan would come down from Perth to assist Charles Horace in propagating fruit trees. Dan would cut the stock and insert the graft, with his nephew Malcolm following behind to do the tying. The Fielder boys were also given the job of collecting jam tins and powdered milk tins from the rubbish dump, at a time when plastic containers were not yet available to nurserymen.

Charles Horace sold the Hocart Road holdings and continued his business in Fryer Road, where he had built a large shadehouse, constructed of tea-tree branches. Here he would propagate plants such as fuschias for the home garden market. He was a hard worker and devoted long hours to his nursery. He expected the same from his sons Norrie, Donald, and Phillip who all worked as young men for their father before going their various ways. Three of them, Daniel, Frederick and Arthur enlisted in WW2. Phillip, after retiring from a 32-year career at Alcoa, ran a small nursery in Mandurah, where he mainly propagated roses.

It was Charles Horace’s second son Malcolm who stayed longest with his father, learning the skills of a trained nurseryman from an early age. He was only 12 when he first found employment alongside his father, riding his bike seven miles after school out to Kernot’s place, where from around 1944 he was paid 35/- per week. Charles Horace managed Kernot’s orange orchard for a number of years and lifted the production considerably, by replacing the Joppa variety of oranges with Valencias.[18] At the same time he was also working in his own nursery.

Charles Horace, a member of the WA Nurserymen’s Association, was well-regarded in the industry. An unsourced article published c1959 described an interview with him, on the subject of using a plant called Trifoliata as a rootstock for citrus trees instead of Citronelle, with the advantage of it being a deciduous variety, which gave the citrus tree time to set fruit before the rush of sap in spring. By that stage Fielder said that he had been using it for ten years, as a way of overcoming problems associated with wet conditions. Trifoliata-based trees developed good lateral root systems and had a better survival rate than those grown on Citronelle stock.

Charles Horace Fielder showing orange trees grown on the prickly Trifoliata root-stock. Image courtesy of Gayle Hall.

At the time CH Fielder stated that 50,000 – 60,000 trees were being supplied from his nursery that year, mostly to commercial orchardists, but many were freighted to farmers and townspeople as far afield as Big Bell, Northampton and Kalgoorlie. Malcolm Fielder recalls that in the early days Sweet Orange root stock was commonly used, before being replaced by Citronelle, which was good for mandarins. Later prickly Trifoliata was recommended, before Citrange, which is still widely used today.[19]

Malcolm recalls that his father remained set in his old ways, but he did eventually acknowledge the advantages of a tractor over the horses he had worked with all his life. In 1964, faced with greater competition in the nursery industry, Malcolm persuaded his father to invest in 300 acres of coastal land, a property which included the ruins of what was known as ‘Hampton’, a former staging post on the Old Coast Road. The plan was to grow lucerne to feed livestock. By this time farmers were benefiting from recommendations by the Agricultural Department that these areas needed applications of trace elements to overcome soil deficiencies.

The blocks at Herbert and Hocart Roads were sold in the 1960s, but Charles Horace continued working in his nursery of 2½ acres at the corner of Uduc Road and Fryer Road until his retirement. With financial problems, he had sold most of his town blocks, as well as 200 acres of the property on the Coast Road. In 1982, at the age of 77, Charles Horace Fielder passed away, after a lifetime of hard work.

A Third Generation – Malcolm Edward Fielder

With a shortage of manpower during the WW2 years, Charles Horace’s son Malcolm had several paid jobs as a boy, including working at Kernot’s orchard, then on a paper round in Harvey, followed by a short period working at the Post Office, then a job at the Cool Drink Factory, where he was earning 35/- per week, considered a good sum in those days. He left when his father persuaded him to join in the family nursery, at a much-reduced starting wage of 2/- per week.[20]

Malcolm Fielder continued working for his father after the other boys had left. He married Gwenneth M. Weeks in 1953, and four years later Charles Horace gave them ½ an acre of land in Herbert Road,where they built their first home, remaining there for seven years. This house was sold following his father’s purchase of 300 acres of land on the Old Coast Road in 1964, and it was agreed that Malcolm could make use of 100 acres of this lighter sandy block, where he planned to build a house and set up a small nursery on part of it. Malcolm was aware by this time that an increasing number of orchardists were by then showing a preference for fruit trees imported from South Australia, convinced that better survival rates resulted from trees planted with more fibrous root systems – ‘like a paint brush’ – rather than those started in the heavier soils of Harvey.[21]

Malcolm and his family lived on the 100 acres on the Old Coast Road, where he established his 2½ acre nursery and ran livestock. He propagated a wide variety of trees, at one stage experimenting with olives grown on root stock obtained from olive trees growing near the Uduc Hall. Malcolm gave up his nursery but his family remained on the Coast Road property, and for five years he supplemented his living by milking cows for a local farmer. Then he was offered a full-time position with the Rose brothers on their large lucerne and potato growing enterprise. There he stayed for 29 years, first working for both brothers, and then after the partnership was split, he worked for Peter Rose, remembered by Malcolm as a considerate employer.[22]

In 2007 Malcolm sold the remaining Old Coast Road property and he and his wife Gwen moved into Harvey where they currently enjoy their retirement.

[1] Ancestry Crew and Passenger Lists, 1852-1930, Ancestry.com Operations. Inc., 2010.

[2] AC Staples, They Made Their Destiny – History of Settlement of the Shire of Harvey 1829-1929, Shire of Harvey, 1979, p.458.

[3] Harvey Roads Board Rates Books, 1922-1930.

[4] AC Staples, They Made Their Destiny – History of Settlement of the Shire of Harvey 1829-1929, Shire of Harvey, 1979, p.459.

[5] Bunbury Herald, 12 August 1924.

[6] Interviews with Malcolm Fielder, 2017.

[7] Sunday Times, 27 September 1936.

[8] Daily News, 28 May 1943.

[9] Western Mail, 24 March 1927.

[10] WA Postal Directories.

[11] South Western Advertiser, 7 July 1933.

[12] West Australian, 23 Feb 1937.

[13] South Western Advertiser, 15 February 1935.

[14] Swan Express, 1 September 1949.

[15] South Western Times, 6 October 1927.

[16] South Western Times, 24 September 1929.

[17] Interviews with Malcolm Fielder, 2017.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.