By Irma Walter & Heather Wade, 2019

It may surprise some readers to learn that there was quite a number of former convict school-masters employed in Western Australian schools in the early days. Rica Erickson has compiled a list of 37 ex-convicts in the public education system.[1] There were others employed privately as private tutors or in Catholic schools, while some, such as Stephen Montague Stout and Archibald Hamblin Livingstone Cole in Bunbury, and Joseph Rossiter in Fremantle, briefly conducted their own private academies. There were six ex-convicts teaching in the Australind area from the 1850s to the 1870s.

As might be expected, the idea of children being taught by former criminals drew complaints from some quarters, fearful of the corrupting influence and dangers inherent in such contact. However, when faced with the alternative of no education for their children due to the lack of qualified teachers in the Colony, there was no other option available.

A statistical report on the state of the colony, conducted by Registrar-General Alfred Durlacher in 1860, revealed that only 65% of the male population over the age of five years (excluding the military, prisoners and ticket-of-leave men), could read and write. For females the figure was lower, a dismal 57%.[2]

Real concerns were voiced that a generation of uneducated youths were roaming the streets or in the bush, creating havoc for law-abiding citizens. Education was being promoted as a necessary civilizing influence over these young people.

Efforts were made to build more schools and supply more teachers, but limited finances and scattered settlements presented major hurdles. Many children continued to miss out on schooling, so a system of compulsory elementary education, which would encompass as many children as possible between the ages of 6 and 14, was introduced in 1871.

However a lack of suitably qualified teachers who were prepared to take up the poorly-paid positions, often in remote locations, presented a massive problem for administrators. Employment of former convicts offered a partial solution. These men were willing to accept the roles as an alternative to hard physical labour.

Governor Weld expressed his reservations in a despatch to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, written on 25 April, 1870:

PUBLIC EDUCATION

There appears to be often a difficulty in obtaining efficient schoolmasters, with the means

now disposable. The fact that many of them are drawn from the ex-convict class speaks for itself; and whilst I should be far from passing a hasty judgement upon individuals, and sympathise with those who are exerting themselves to regain the position they have forfeited, it must be admitted that the convict or ex-convict class are not, as a rule, fitted for the education of the young, either morally, or intellectually, nor is their employment as schoolmasters.[3]

Many hardships faced teachers in lonely one-teacher schools. Problems such as alcoholism, absenteeism and misconduct were features of reports concerning teachers from all backgrounds, not only convicts. Some remained at the same schools for a number of years, giving excellent service, while others quickly sought better paying roles elsewhere.

The availability of former convicts for these teaching roles provided the basis of a reliable system of education in WA. For the men themselves, the position gave them respectable employment and improved their status within the community.

Three former convicts who taught at the Australind School –

Henry Gillman

Stephen Montague Stout

Joseph Farrell.

At Parkfield School were –

George Newby Wardell

Adolph Hecht

Daniel McConnell

…………………………………………………….

AUSTRALIND SCHOOL

(1) HENRY WILLIAM ISAIAH GILLMAN, alias Henry Jones, (1825 -1902)

Henry Gillman’s career as the first schoolmaster at Australind was of short duration, but his story is of interest because of his occupation as a storekeeper and trader in the small towns of Bunbury, Busselton and Fremantle between 1859 and the 1880s. Henry was a highly ambitious individual and some of his dealings were less than scrupulous, and a study of his life gives us a window into the commercial environment of that period.

Little is known about Henry Gillman’s background prior to his conviction in the Central Criminal Courts in London in 1851, when he was found guilty at the age of 26 of having stolen goods including a shawl valued at 6s, along with 6 curtains and 2 vases, value 27s. They were the property of Betsy Salaman, daughter of a feather-bed maker, of West Conduit Street, Bloomsbury, in the West End of London.[4]

At the time of the 1851 census, Henry Gillman was in Millbank Prison. He is described as an unmarried 26-year-old dentist, born at Norwich in Norfolk. From the evidence given at his trial, Gillman was at that stage a dealer in second-hand goods and had a previous police record, with another case pending. Due to his multiple petty crimes he was sentenced to ten years’ transportation. Henry William Isaiah Gillman (Reg. No. 4440) arrived at Fremantle, Western Australia, on board the Clara, on 3 July 1857.

He was sent down to the Bunbury Convict Depot soon after his arrival. Marshall Waller Clifton, Chief Commissioner of the Western Australian Land Company at Australind, was immediately interested when Gillman approached him on 13 April 1858, offering himself as a schoolmaster for the small settlement a few miles north of Bunbury. Henry was found accommodation with the Offer family and one of the small buildings in the Australind township was set aside for a classroom. He was introduced to the neighbours and on 19 April 1858, Clifton recorded that ‘Gillman had to go to Bunbury to get his Ticket of Leave’, necessary before he could commence teaching.[5]

A little later that month on 28 April 1858, Clifton’s journal records the arrival of a young Irish servant, Annastasia Kennedy (b. 1835), one of a group of 59 single women who had arrived in Fremantle on 8 August 1857, on board the City of Bristol. [6]

A strong attraction developed between schoolmaster Henry Gillman and Annastasia, a situation which would have concerned the Cliftons, who considered themselves responsible for the young woman’s welfare. On 26 December 1858 Clifton tersely recorded: ‘Row with Gillman but settled on condition of instant marriage.’ [7]

The following day an altercation erupted in the household, when one of the workers under Clifton’s son Gervase came to the house and assaulted both Anna and her employer Marshall Waller Clifton (not a young man), who recorded the incident thus:

After Dinner Patrick Clancey, Gervase’s man having struck Anna, I went to speak to him when he committed a brutal assault on me, knocking out two teeth & would have killed me by a Blow from a poker but for Crowd having seized him.[8]

Patrick Clancey (Reg. No. 3330), was a former military man with a quick temper, who had been sentenced to 14 years’ transportation after being found guilty of striking his superior officer at Gibraltar in 1853.[9] Clifton swiftly took measures to ensure the safety of his household, recording the following actions on the day of the attacks:

Swore in George, Offer & Guthrie as Special Constables, (…?) my Cart & lodged him in Gaol. Very ill from the blows.[10]

Early in 1859 Annastasia made a couple of trips into Bunbury, where her fiancé Henry Gillman was already working on his plans to open a store. Clifton agreed to give her away at the wedding ceremony, conducted by the Roman Catholic priest in Bunbury. He described these events as follows:

Jan 13 – Anna went with Frank in Donkey Cart to Bunbury & got back at 10 at night.

Jan 16 – Anna went with Gillman on Horseback and returned.

Feb 9 – Rode down to Bunbury at ½ p’ 5 to Anna’s Marriage to Mr Gillman. Gave her away at Sergeant Whites. She was married by Mr Lynch the R. C. Priest. Breakfasted at Louisa’s with Lady & Mrs Wm. Bunbury arrived last night.[11]

Gillman did not re-open the Australind School in the New Year, being busy establishing his store. During February and March Clifton reported that he sent grapes, other fruit and onions down to Gillman in Bunbury, indicating that he was already trading.[12] The position of teacher at Australind was not mentioned again in Clifton’s journals until the arrival on 10 May 1859 of another ticket-of-leave man, Stephen Stout, to take on the role.[13]

Henry Gillman’s store at the corner of Victoria and Stephen Streets in Bunbury was opened in April 1859, where Bon Marché Mensland now stands. Ray Repacholi quotes Algernon Clifton’s account of the history of this prime retail site, stating that three blocks, two facing Victoria Street and one facing Stephen Street, were purchased by Resident Magistrate George Eliot in 1852, and were leased to Gillman from 1858 until about 1873. Clifton’s recollection of the building was of ‘a low, rambling wooden building with shingle roof, the shop facing Victoria Street with verandah, and the home on Stephen Street standing back about 25 feet.’ The property became known as ‘Gillman’s Corner’.[14] Gillman advertised the opening of his store in April 1859:

HENRY GILLMAN’S NEW STORE, BUNBURY.

WILL be opened this week, where the business recently established,

with very considerable success, will be conducted on sound principles of commerce,

so that much of the trade, hitherto allowed to pass from the immediate locality, can now be retained here, to the advantage of the Storekeeper and his customers, as well as the district generally.

A carefully selected stock of goods, suitable to the season, just coming in.

N.B. – During H. Gillman’s visit to the Swan, the present and following week,

the business will be conducted at Bunbury as usual.

Bunbury.

April 25, 1859.[15]

There appears to be some uncertainty about whether Gillman built the small shop and house. He certainly extended the building in 1860, when he assured his customers that service would not be interrupted while extensions were being built.[16] Where Gillman obtained the finance needed to start up his business is not known. Clifton regularly wrote that Henry Gillman had called in at Australind on his trips to Perth and Fremantle, presumably for the purpose of obtaining more stock, with Clifton sometimes giving him mail to carry. The friendship between the two couples continued, with Henry’s wife Anastasia occasionally going out to visit the Cliftons at Australind, sometimes staying overnight.

Within two months of opening the store, Gillman’s advertised stock grew from a modest list to an extensive range of household, farming and personal goods, as detailed in this advertisement in June 1859:

HENRY GILLMAN,

BUNBURY.

TO prepare for a larger and more general class of goods, ex recent arrivals, Henry Gillman will, during ensuing three weeks, offer his present well-selected stock, at considerably reduced prices, for Cash.

Ladies and gentlemen’s wearing apparel generally, woollen cloths, moleskin, cord,

merino, plain and figured lustre, muslin and print dress pieces, hosiery and haberdashery, children’s and infant’s clothing, calicoes, linen, chintz, jaconet muslin, damask, dimity, flannel, lace, edging, insertion, crochet, Limerick lace and worked muslin collars, cuffs, denim, Holland lining, salad and lamp oil, candles, mustard, pepper, salt, sardines, pimento, cloves, coffee, tea, sugar, rice, tobacco, pipes, soap, starch, soda, blue, perfumery, hair brushes and combs, tooth brushes, saucepans, kettles, delf, stone china, glass-ware, American buckets, cutlery, and hardware, watches, clocks, electro gilt and silver guards, brooches, bracelets, wax dolls, children’s alphabet and toy books, school books, histories, romances, biographies, novels and tales, stationery generally, Jew’s harps, Manilla rope, fishing lines, whip cord, hank and ball twine, packing needles, gutta percha dishes, fancy baskets, umbrellas, fancy bags, powder, shot, percussion caps, hammers, axes, nails, tin tacks, screws, hinges, bolts, padlocks, &c, &c, &c.

Wheat, Barley, and Potatoes wanted immediately, for which half will be paid in cash and half in stores.[17]

Bunbury, June 13, 1859.

As well as the usual range of items to be found in a general store, the ambitious young man soon extended into other areas of business. In July 1859 he was advertising as agent for the schooner Amelia and as a produce broker, ‘willing to sell for cash or in barter’.[18]

In July 1861 he advertised that he had acquired the rights as agent for the Perth Gazette newspaper in Bunbury – a move that would have helped cover the costs of his frequent and extensive advertisements in that paper.[19] In 1861 he received his Conditional Pardon.[20]

During 1863 Gillman advertised a change of name to ‘WATERFORD STORES’ for his business in the Perth Gazette, along with an announcement that he was adding an Auctioneering Branch to his business.[21] The new name was possibly derived from his wife’s place of birth in Ireland.

In 1864 the Gazette posted an announcement that a tender had been accepted from H Gillman to supply the timber required for the jetty at Bunbury for £339.[22] Not content with this rapid – and some might say reckless – rate of expansion, the following year Gillman was advertising the sale of ‘Wine, Beer and Spirits’, assuring customers that imported supplies would be restricted to gallon or package products, (in order to comply with regulations), while ‘Colonial Wines’ were available in quantities of one pint and upwards. He also announced that – BUTCHERING in its General Branches will be added to the Business during the ensuing Month.[23]

View over Bunbury, probably taken by ex-convict Stephen Stout in 1867, showing Gillman’s store on the corner opposite Bunbury’s Pro-Cathedral, at middle right side of picture.[24]

Records show that in the years between 1862 -1874 Gillman employed a total of 74 ticket-of-leave men in a wide variety of jobs which included many sawyers and a brickmaker in 1869, a carpenter in 1871 and a lime burner in 1866.[25]

A tragic event in the lives of Annastasia and Henry Gillman occurred in 1864 with the death of their small daughter Kate Anna, aged two years. The sad situation was made much worse by wrangling between the local clergy over where the child should be buried, as reported in the Inquirer:

A short time ago a child, the daughter of Mr H. Gillman, of Bunbury, was so severely scalded that she died, and on Sunday, the 11th instant, she was buried, under the circumstances now stated. The procession moved towards the Roman Catholic Cemetery, where the child was to be buried, but upon arrival the priest did not make his appearance.

They waited for some time, when the Rev. Mr McCabe came out, and informed Mr Gillman that the child could not be buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery, because the bell had tolled at the Protestant Church the procession passed.

The consequence was that the mourners had to wait in the pouring rain for two hours until a grave was dug in the Church of England Cemetery. The poor child was at last laid in peace at that spot, the Rev. H. Brown performing the funeral service.

Our correspondent states that the affair caused some little excitement in the usually quiet town. The father of the child was a Protestant, and the mother a Roman Catholic.[26]

In 1867 it was reported that Mrs Gillman made a trip to Perth on board the Bridgetown, accompanied by four children and a servant. The children would have included her three surviving daughters born by that time, Florence Esther (b.1861), Mary Emma (b.1864), and baby Laura Lisette (b.1867). The other child would have been her son Edward William Henry Gillman, born 1865.[27] Two more daughters, Rose Henrietta (b.1869) and Amy Ada (b.1870) were born later in Bunbury, a total of seven children.

In 1868 it was announced that another of the children had died, this time Laura Lisette, aged 11 months.[28] The death of infant children in those days was unfortunately an all too common event.

In 1868 an unusual charge was brought against HW Gillman in the Perth Police Court, with having driven ten head of cattle through the city after 8 o’clock in the morning, contrary to the law. He was fined £5.[29] Later that year Henry was praised for his quick thinking when he helped to resuscitate a drowning child in Bunbury. This occurred at a time when much of the town was poorly drained and prone to flooding:

An accident occurred on the 28th instant, when a little boy, the son of Warder Craig, fell into a pond of water, while playing with some companions. The poor little fellow was unfortunately submerged for some time before the other children could muster courage to call for help, when a man named Kelly rescued him, but not before he was quite insensible. Much credit is due to Mr. Gillman, who, with much presence of mind, ran with the child to his own house, and used every effort to restore animation, till relieved by Dr. Sampson, who, with patient and skilful treatment, was, under Providence, the means of bringing back the life which was at first despaired of. [30]

In 1869 there was mention of a joint venture between Gillman and another local businessman, William Spencer, when Gillman bought a half-share in the ownership of a coastal vessel:

The ‘Clarence Packet’ which is now jointly owned by Messrs. Spencer and Gillman, plies regularly between this port and Fremantle. The increased accommodation afforded by this neat little schooner, and the complaisance of her excellent captain, Harry O’Grady, will act as an additional inducement to persons travelling to the Swan and vice versa to avail themselves of the comfort this vessel affords.[31]

In 1870 Henry Gillman was elected as a member of the Bunbury Town Trust. He was interested in local affairs and was outspoken on a number of issues, including support for Responsible Government in the Colony.

At the time of Governor Weld’s first visit to Bunbury that year it was reported that a decoration committee had done the town proud, with two welcome arches erected in the main street, and that ‘the stores of Mr. Spencer and Mr. Gillman were decorated with a profusion of flags.’ Not to be outdone, the prisoners erected at the approach to the town, on the Australind road at the back of the Convict Depot, an elegant triumphal arch, decorated with flags and streamers, and inscribed ‘WELCOME’.[32]

According to a Bunbury correspondent in 1869, Gillman’s business soon expanded into the export trade:

The Sea Ripple has arrived in port and is fast loading with sandalwood for Singapore.

This is another instance of the indefatigable exertions of our fellow-townsman, Mr. Gillman, who has been instrumental in establishing a lucrative trade in sandalwood. There are now about forty teams on the road constantly employed in carting this article of export into Bunbury. Everyone who can raise a team of horses is off sandalwooding, and to judge from the many who engage in the venture it must be a paying speck.

I think the horses, about 40 in number, exported by Mr. Gillman to India, the finest looking I have seen for some time; they far exceed prior shipments.[33]

However, the good times for the Gillmans were coming to an end. During a general downturn in trade in the colony, Henry found himself deep in debt. His troubles were mostly of his own making, due to his overly ambitious expansion plans. At a meeting of creditors in 1870 it was reported that Henry William Isaiah Gillman’s liabilities amounted to over £10,000, a large sum in those days:

A MEETING of the Creditors of Mr. W. H. Gillman, Bunbury, was held yesterday at Mr. Samson’s office. Mr. Gillman stated his debts as about £10,000 and his assets £12,000 Messrs. E. Newman. and Mr. W. D. Moore, were appointed trustees, pro tem.[34]

In February 1870, the Herald in Fremantle drew attention to the parlous state of the WA economy, citing Gillman’s case in particular:

…Business is being conducted on all hands with extreme caution, and it is felt it will be better to let some of the tottering storekeepers fail than to prop them up. Mr. W. H. I. Gillman of Bunbury has just failed for £10,000 and has assigned his property to trustees for the benefit of his creditors. This seems to be the method in favor now for winding up estates. It is thought to be more economical than the Insolvent Court, and so long as the trading community remains dissatisfied with the Insolvent Act, we suppose they will continue to accept assignments. Under certain circumstances, and where practicable there can be no doubt it is more convenient to Creditors and the Insolvent than the Court.[35]

In May 1870 the first sale of Gillman’s stock and property took place, advertised as follows by auctioneer James Moore:

BUNBURY.

EXTENSIVE AND IMPORTANT SALE BY AUCTION

ON MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY,

SATURDAY, the 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th MAY, 1870.

PURSUANT TO INSTRUCTIONS FROM THE TRUSTEES

TO THE ESTATE OE MR. GILLMAN

MR. JAMES MOORE

WILL Sell by Public Auction, on above dates, at the Warehouses of the Waterford Stores, Bunbury —

All the Stock-in-Trade, Business Appliances,

Carts, Waggons, Whims, Horses, Gear, &c. &c. &c.

Properties of the Estate.

THE value of Property thus offered will amount to SEVERAL THOUSAND POUNDS, but it is not practicable to particularise the items in this advertisement.[36]

Another sale took place in June 1871:

ESTATE OF H. W. I. GILLMAN. Final Sale by Auction.

MR. JAMES MOORE Is instructed to sell by public auction, at Bunbury,

On TUESDAY, 22nd June, 1871.

A LARGE quantity of Sandalwood in the bush (very large, cleaned, and carted together); a lot of Railway sleepers, 10 feet long by 10ft. x 5ft.; Scantling; 2 new Timber Whims, with broad strong wheels 7ft. 6in. in diameter; 1 large Weighing Machine (30 cwt.); a quantity of Bricks, Shingles, Paint, Nails, Cart and Wagon Covers, Cart Harness, and Bullock and Trace Chains. Broom and Scythe Handles; Cross-cut and Pit Saws, Axes, Stockings, Crinolines, and sundries too numerous to mention in detail.

A number of HORSES and CATTLE.

At the same time will be offered for sale, The Equity of Redemption of all that extensive and valuable property situated in the best position in Bunbury, comprising: —

1st — Two five-roomed Houses, attached, with entrance-hall to each.

2nd— One quarter-acre Allotment in —— Street, with dwelling-house and smithy, let for 6 years at £20 per annum.

3rd — Adjoining No. 2, a well and strongly built Brick Shed, with thorough roof, 91 feet long by 14 feet, and very strongly-built Warehouse, 66 feet long by 28 feet. The valuable front of this Lot is unoccupied.

4th — Above one quarter acre, adjoining No.3, with strong unroofed shed or warehouse, 115 feet long by 28 feet, 14inch brickwork. This Lot also has a valuable frontage unoccupied.

5th — Extensive Buildings, comprising dwelling-house, kitchen, bake-house, and outhouses, with extensive stables. This Lot is let at £40 per annum, as a model lodging-house.

6th — Forty acres fee-simple Land, suitable for a paddock, within four miles of Bunbury.

7th — Front Lot, Victoria Street, Bunbury.

8th— Do., do., do.

9th — Two Allotments, well situated in the townsite of Busselton.

The whole of the above Lots, 1 to 9, are included under a mortgage for £750, and whether offered separately or together, will only be sold on realising collectively that amount.

Any further information may be obtained on application, personally or by letter, to Mr. W. B. MITCHELL, Local Agent for the Trustees, at Bunbury. # Terms at time of Sale. 1st June, 1871.[37]

The business premises and adjacent house at the corner of Stephen Street, previously occupied by the Gillmans, were put up for sale in September 1871. Where the family was living by this time is not known:

Bunbury town lots, 232, 233, 234, formerly in the occupation of Mr. Gillman; the buildings on these are substantial and valuable, forming complete business premises, with commodious residence.[38]

In 1871 Gillman’s remaining investment blocks were advertised for auction. (Note that Lot 3, occupied by blacksmith Anthony R Keen, was adjacent to the house block formerly occupied by the Gillmans in Stephen Street.)

VALUABLE FREEHOLD and BUSINESS PROPERTY in and near Bunbury and Busselton, in Western Australia.

Mr. James Moore

HAS received instructions from the Trustees of the assigned Estate of Mr. HENRY WILLIAM ISAIAH GILLMAN to offer for sale by public auction at the Wellington Hotel in Bunbury, on THURSDAY, the 30th day of November, 1871, at two o’clock in the afternoon, in the following or such other lot or lots as may be determined upon at the time of sale, and subject to conditions to be then produced:

LOT 1.- All that piece or parcel of land or ground situate about 4 miles from the town of Bunbury, in a Southerly direction, and known as “Wellington Location 267,” containing 40 acres, more or less, adjoining Mr. E. Flaherty’s property.

LOT 2.- All that allotment, piece or parcel of land situate in the town of Bunbury, aforesaid, fronting to Wellington Street, and known as “Bunbury Town Lot No. 201,” together with the two cottages and buildings erected thereon, and now in the several occupations of Mr. Sub-Inspector Dyer and Mr. A. Baskerville, and producing a gross rental of £32 per annum.

LOT 3.- All that other allotment, piece or parcel of land or ground, also situate in the town of Bunbury aforesaid, and known as “Bunbury Town Lot No. 235,” with the blacksmith’s shop and dwelling-house now standing there-on, and in the occupation of Mr. A. B. Keen, and producing an annual rental of £20.

LOT 4.- All those three other allotments, pieces or parcels of land, forming one block, situate in the said town of Bunbury, and known as “Bunbury Town Lots Nos. 236, 237, and 238,” together with all the several buildings and erections, whether brick built or wood, now standing and being thereon, and part now in the occupation of Mr. A. Atkins, storekeeper, and. producing a rental of £30 per annum.

LOT 5.- All those two several allotments, pieces or parcels of land situate in the town of Busselton in the said colony and known as “Busselton Town Lots Nos. 127 and 128.”

For particulars apply to the Auctioneer, or Mr. W. B. Mitchell, both of Bunbury, or at the office of Mr. G. W. Leake, Solicitor, Perth.[39]

As a result of the sales, Gillman’s creditors received their first dividend in December:

A FIRST dividend of 2s. 6d. in the pound will be payable, and may be obtained on application to Mr. Edward Newman, of Fremantle, one of the Trustees, on any day after Tuesday, the 19th instant.

Creditors will be required to prove their debts by the usual statutory declaration, and by the production of Bills of Exchange or Promissory Notes where any such exist.

Forms of such declaration may be obtained from Mr. Newman, or from the undersigned.

G. W. LEAKE,

Solicitor to the Trustees.

Perth, Dec. 14, 1871.[40]

The winding-up of Gillman’s business affairs was a long-drawn-out process. In 1873 a final sale of Henry’s remaining property was advertised. It was not until 1874 that his creditors receiving their second settlement of two shillings in the pound.[41] In the meantime, Annastasia had established her own business in Fremantle:

Mrs. GILLMAN, General and Commission Store, (Opposite Lodge’s Hotel,) HENRY T., FREMANTLE. ESTABLISHED IN HER OWN SOLE RIGHT. Goods of excellent quality, CHEAP, FOR CASH. PATRONAGE RESPECTFULLY INVITED. COMMISSIONS from the public generally and friends at the South punctually despatched.[42]

Following the collapse of his business, it is known that Gillman was trading in cattle and sandalwood, as became evident when he and his associate John McGibbon, commission agents, appeared in the Supreme Court in Perth, charged with fraud and conspiracy. It was alleged that in 1874 they conspired to defraud a Bunbury butcher named Henry Albert, by offering to supply him with sheep and cattle. They received an advance payment from Albert, after assuring him that Gillman had enough stock to fulfil the order. Shortly afterwards the pair were declared bankrupt. Gillman faced the Fremantle Police Court in September 1875, charged as follows:

Henry William Isaiah Gillman, was charged with being bankrupt on the night of the 21st, or on the morning of the 22nd day of August, 1874, and within four months next before the presentation of the bankruptcy petition against him, did fraudulently move a certain part of his property to the value of £10, contrary to the statute ; and also, that on or about the 24th day of February, and the 5th day of March, 1874, he by means of false pretences and fraud, obtained credit from one Henry Albert to the amount of £373 10s.. contrary to the statute; and he was further charged with obtaining goods on credit by means of false representations and fraud from one William Dalgety Moore, and not paying for them contrary to the statute.

During the hearing, evidence was given by two Bunbury policemen that Gillman had been systematically moving stock from his business premises, contrary to the statute of bankruptcy, across the road to a shop owned by a John Buchanan. It appears that Buchanan and Mrs Gillman assisted the accused in the fraudulent act. The statement of one of the policemen was reported as follows:

Francis Walsby Holland, having been sworn, said:-

I am a police constable, and was stationed in Bunbury in August 1874. I know Gillman. I know his store at Bunbury. I remember the 21st August, 1874. The store was apparently not well stocked on that date; it had for some time previously gradually been getting less. I saw Gillman on the night of the 21st August, for the first time. I believe at half past ten he was standing on the threshold of his door. I know a man named Jno. Buchannan (sic), a storekeeper, living at Bunbury. I saw him that night and the same time I saw Gillman. He was walking in front of his store: his store is opposite Gillman’s.

I saw Gillman about quarter of an hour after; he passed me in the street; he had nothing with him then. I was about 300 yards down the street away from the store, he subsequently passed back again walking on the other side of the way, that is on the side on which Buchannan’s store is. It was a dark night. I next saw Gillman about 11 o’clock.

I again saw Gillman at half past eleven coming out of his private door, (the house and store are all in one), he was carrying a bundle under each arm. He went across to Jno. Buchannan’s, I saw him go there. Buchannan came out with Gillman from his (Gillman’s) private door. Buchanan had also a bundle; they were all large bundles about two feet long and 6 inches deep, they looked like rolls of drapery; they went to Buchannan’s and both entered with the bundles, and entered by Buchannan’s private door. I saw this process repeated between half past eleven and a quarter to three.

I saw Buchannan and Gillman pass between the two houses with bundles ten times. Nine times Buchannan and Gillman were together; then Buchannan went across by himself from Gillman’s to his own house, and returned back to Gillman’s; they then returned together, Gillman was carrying a large looking glass, this was the last trip that was made. Gillman then went into his own house. I waited some time and seeing the light go up stairs I then went away; during the time the trips were being made I saw the light was sometimes in the store and sometimes upstairs. [43]

[Note: The said John Buchanan was also a former convict, having arrived in WA on board the York in 1862, following a sentence of 14 years at the Warwick Assizes. Buchanan continued to operate his store in Bunbury up until 1878, when he notified his customers that he intended leaving the Colony.[44] However in May of the following year it was announced that he was deceased.[45]]

In October 1875 it was reported that Henry Gillman and two of his children had a lucky escape while travelling from Fremantle to Perth:

Accident: – On Thursday afternoon last as Mr. H. W. I. Gillman of Fremantle in company with two of his children, was driving towards the convent in Perth, the horse shied opposite the Mechanic’s Institute, throwing Mr. Gillman forcibly to the ground. The horse continued on at a tremendous pace in the direction of the convent, and at the last turning the little boy jumped out, leaving his little sister alone in the vehicle. At Hardy’s corner, the vehicle came in contact with a post and upset. By a wonderful stroke of good luck, it turned out that none of the occupants were in any way seriously injured, beyond the fright and the shaking. It may certainly be looked upon as a miraculous escape.[46]

During his trial in October 1875, Gillman mounted his own defence, with the Judge allowing him a couple of hours to press his claim of innocence. On 11 October 1875 Gillman was convicted of ‘inducing a person by false pretences to accept a valuable security’. John McGibbon, another expiree (Reg. No. 1425), was convicted on a ‘count of conspiracy and two other counts’. Both were sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour.[47]

The lengthy report of their trials in the Herald newspaper concluded as follows:

…The jury, after an hour’s deliberation, convicted Gillman on the two counts, finding McGibbon guilty of conspiracy only. His Honor in passing sentence said:

Henry William Isaiah Gillman, you have been charged with obtaining money by

means of false pretences, and you John McGibbon have been charged with conspiring to defraud. The jury who have had you in charge have given their attention all day to your case, resulting in a verdict against you both. The judgement of the Court is that you each be confined to hard labor for twelve calendar months.

The Attorney General having intimated that he did not intend to proceed with any other indictments against the prisoners, they were removed and locked up, shaking hands with a number of friends as they passed out of the court.[48]

Gillman was released from prison on 6 May 1876. During his incarceration Annastasia was operating her own small business in Fremantle, with a shipping list reporting that Mrs H Gillman had a piano shipped from England in June 1876.[49] Undaunted by his term in prison, Gillman was soon back in business after his release, this time in High Street, Fremantle, along with his wife Annastasia. He must have felt confident that he could win back the trust of suppliers and the public. How well the locals responded to his overtures to do business it is hard to tell:

H. W. I. GILLMAN, CENTRAL COMMISSION AGENT,

AND General Commission Salesman, High Street, Fremantle,

To large or small buyers and sellers this Agency will be found of great advantage.

GENERAL MERCHANDIZE, Houses, Lands, Runs, Live Stock, Produce, Furniture, Effects, Personal Wares, &c.; &c., &c. Sold or purchased on specific commission or bonus—according to agreement—with fidelity, silence, and despatch.

Correspondence, accounts, Documentary Work &c., attended to.

Registry for general requirements conducted with great energy on a reasonable scale of fees.

N.B.—At MRS. GILLMAN’S RETAIL COMMISSION STORE, conducted on the same premises, good general wares &c., will be found at reasonable rates, where the kind patronage of the public will meet with attention and thankfulness.[50]

A few weeks later they moved to new premises in Pakenham Street, opposite Leake Street in Fremantle.[51] In 1879 Gillman was listed as a storekeeper in Busselton.[52] By 1882 he was advertising as a produce merchant there:

H. W. I. GILLMAN,

GENERAL AGENT and COMMISSION SALESMAN.

THE PRODUCERS’ EXCHANGE

AND

Working Man’s Mart.

A GENERAL BUSINESS being in course of establishment in connection with the Vasse trade, greatly increased facilities will be afforded to customers.

Steadiest rate allowed for sound produce.

Largest value given for money.

Busselton, 1882.[53]

The following testimonial confirms that the Gillman family was in Busselton in the 1880s:

TESTIMONIAL:

Busselton, March 11th, 1882.

Professor B. Mitchell, Oculist and Aurist, Perth.

Dear Sir, — I beg to tender you the sincerest thanks of myself and family for your attentive and effectual treatment of my daughter’s eye—the sight of which, though completely obscured when she came under your treatment, is now perfectly restored.

Yours truly,

H. W. I. GILLMAN.

Miss Gillman, from the Vasse, consulted the professor on the 16th inst. Fourteen months ago she entirely lost her sight in the left eye. After consulting three medical gentlemen they pronounced her case hopeless; on the recommendation of Dr. Sampson, of Bunbury, her mother led her to consult the professor and it has resulted in the almost entire recovery of her sight; she can now read small print, and in a few days her sight will be restored. [54]

An altercation which occurred at the Busselton store in 1882 between Gillman and a respectable local woman would not have earned him any favours in the town:

During the past week, one of our storekeepers, Mr. H. W. I. Gillman, has figured in the court for using abusive language to a customer. The facts brought forward in evidence were as follows. On Saturday, Mrs. David Abbey having a cheque for some £30 odd, went to Gillman’s store and asked that gentleman to change the cheque, deducting the amount due to him. On reaching home Mrs. Abbey discovered that the change given was £1 short and went on the following day (Sunday) to rectify the mistake. It appears Mrs. Abbey had herself made a mistake in putting down the respective amounts of some of the cheques given her, but knew she was correct in the total amount. She averred that Mr. Gillman accused her of attempting to defraud him and called her some opprobious names. Gillman subsequently discovered that he had made a mistake, sent for the customer, gave her the pound, and tendered an apology. This Mrs. Abbey did not accept but took out a summons. Messrs. Cookworthy and Gale, J.P’s, who adjudicated upon the case, fined Mr. Gillman ten shillings and costs.[55]

There is evidence that Gillman was acting as auctioneer at a sale in the Vasse area in 1884.[56] Meantime he was heavily involved that year in supporting candidate George Layman in the election campaign for a Legislative Council representative, with the issue of Responsible (Independent) Government being the main topic of discussion. Like many others of the convict class throughout the Colony, Gillman was strongly in favour of independence from England. The election was a lively one and when Layman won with a comfortable majority, the jubilant crowd gave three cheers for Layman and three cheers for his supporters Gillman and Cross, then celebrated the victory as follows:

When Mr. Layman attempted to leave in his carriage from the Ship Tavern, a rush was made for it and the horses were taken out and the carriage containing the successful candidate was run along the main street by a number of his supporters down and then back again to the Ship Tavern picking up Mr. G. Cross on the road. After this Mr. Layman was allowed to go home in peace; the majority obtained by Mr. Layman is the largest ever obtained in the District.[57]

[Note: It was not until 1890 that Responsible Government became a reality for WA.]

It appears that the Gillmans were operating businesses in Busselton and Fremantle at the same time. The business in Fremantle High Street survived for a number of years, with advertisements offering a wide range of goods in 1885:

EXCELLENT QUALITY AND CHEAPER THAN ANY OTHER.

EHRHARDT’S LONDON LEVER WATCHES

Capped and jewelled in strong highly finished sterling silver hunting Cases. A watch guaranteed to resist influence of climate and rough wear. A Number of these watches have been placed with MR. GILLMAN for sale under circumstances which enable him to offer exceptional advantages to purchasers. The usual price of these Watches is from £6 10s. to £7 10s. H. W. I. GILLMAN is selling them at £5.10s.[58]

H.W.I. GILLMAN High Street, Fremantle.

FOR Choice Southern Butter, go to H. W. I. GILLMAN, HIGH ST. FREMANTLE. FOR high class Tea and Sugar at moderate rates, go to H. W. I. GILLMAN, HIGH STREET, FREMANTLE.

FOR Crewel and washing Silks of pure quality, brilliant color and extensive shade, go to H. W. I. GILLMAN, HIGH STREET, FREMANTLE.

FOR good calico, and cheap, go to H. W. I. GILLMAN, HIGH STREET, FREMANTLE.

FOR a thousand and one articles of taste, utility and comfort, go to H. W. I. GILLMAN, HIGH STREET, FREMANTLE.

SPECIALTIES – Large Music Box, Martini-Henry Rifle, Canvas Water hose.

H. W. I. GILLMAN. HIGH STREET, FREMANTLE.[59]

A trader as well as a shopkeeper, in 1885 Gillman advertised the sale of oranges and potatoes by auction at the Fremantle jetty.[60] During this period Gillman was being pursued through the courts over a number of petty debts. Matters were made worse when a disastrous fire threatened several High Street premises in December 1885. A graphic description appeared in the Herald:

Disastrous Fire at Fremantle

On Sunday morning at about 2 o’clock the store of Mr. Geo. Davies in High street was discovered to be on fire. The alarm was at once given by ringing the fire bell, and in a short time the recently organised Fire Brigade, with the engine and new hose were on the spot. Under the direction of Captain Newbold the engine was connected with the hydrant at the corner of Packenham street, and the men told of their respective duties. The hose was quickly connected and, as it was quite impossible to do anything to save Mr. Davies’ store, all exertions were directed to save the adjoining premises, a block of connected buildings, occupied by Mr. Gillman, Mr. Mitchell the confectioner, Messrs Pearse Bros. bootmakers and Mr. D K Congdon. The fire had got a good hold of the roof of the first building where Mr. Gillman is living with his family, awaiting the finishing and furnishing of the shop below.

Upon this point the water was brought to bear, the men in charge of the hose stuck to their post most gallantly, the burning roof threatening to fall in and engulf them. Another party further on was stripping the shingles from the roof so as to check the progress of the fire, while others were engaged in removing the goods and furniture from the threatened buildings; after a time, the determination of the hose men not to retire while it was possible to keep the flames from extending along the roof beyond the point it had reached before they could take up their position was rewarded; it was evident the fire was under control, and that the imminent danger of the whole block of buildings being burnt to the ground, which at one time appeared almost certain, was past, the great crowd that assembled felt relieved as the flames subsided and began to disperse There was no great excitement and the men of the fire Brigade and the volunteers who took a direct part in extinguishing the fire, behaved with the most commendable coolness and resolution. Nowhere in the world could men have behaved better, or shewn more daring courage.[61]

There are indications that Gillman’s Fremantle business was struggling after the fire. He took some of his merchandise to Northam and Newcastle, where he held auctions in early March 1886.[62] Over several weeks he was advertising for rent – ‘TWO or THREE rooms furnished or unfurnished in a HOUSE beautifully situated in Fremantle.’ [63]

His usual advertisements for the Fremantle store continued until 12 June 1886, six months after the fire. However, at the end of 1886 Gillman’s goods were being auctioned by the Bailiff in Fremantle, in order to recover unpaid rent owed to a man named Mason.[64]

Henry Gillman’s business career in WA was at an end. On 23 March 1887 he quietly slipped out of Fremantle on board the ss Franklin, bound for Melbourne, accompanied by his son Edward. By this stage Henry was over 60 years of age.

His eldest daughter Florence had previously sailed to Adelaide in 1885. In June 1887 his wife Annastasia, still in Fremantle, was advertising for ‘three Gentlemen Boarders to take up comfortable rooms with a family in the centre of High Street.” [65] Later that year her daughter Mary Gillman advertised household goods for sale:

S O L O M O N & Co.

Have received instructions to sell by auction, by order of Miss Mary Gillman,

on the premises, High-street, Fremantle, as above —

A quantity of HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE, consisting of tables, chairs, cane

sofa, canterbury wardrobe, bedsteads, palliasses, books, feather beds and bedding, and a quantity of useful kitchen utensils, &c.[66]

Annastasia and three daughters left Fremantle for Victoria on 25 February 1888, to join her husband.[67] Her daughter Rose probably left the ship in Adelaide, as records show that she joined the Sisters of St Joseph at Kensington, South Australia, on 4 March 1888.[68]

A NEW IDENTITY

Little is known about Henry William Isaiah Gillman and Annastasia Gillman (née Kennedy), once they reached Melbourne. It appears that they changed their names, probably hoping to leave Henry’s convict record and his history of financial problems behind them. We find them using the names ‘Henry and Hannah Jones’, while their children were using either the surnames ‘Jones’, or ‘Gillman-Jones’.

Where Henry Gillman found employment in Victoria is not known. His death notice appeared in 1902, under the assumed name of Henry Jones:

JONES.— On the 4th May, at his residence, 482 Albert-street, East Melbourne, Henry, the dearly beloved husband of Hannah Jones, and beloved father of Florence, Mary, Edward, Rose and Amy Jones, aged 78 years. R.I.P.[69]

Henry’s wife Annastasia Gillman (née Kennedy), known as ‘Hannah Jones’, passed away at a private hospital in Melbourne in 1917. Her previous address was 121 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy. Her death was registered under the name ‘Anna Jones’:

JONES.— On the 10th August, at private hospital, Anna, loved mother of Madame Antaud (sic), Melbourne; Mrs. Epiro (sic) Turner, Sydney; E. Jones, Albury; and Sisters Aelred and Gabriel, Adelaide. R.I.P. [70]

CHILDREN OF HENRY AND ANNASTASIA GILLMAN

Seven children were born in Bunbury WA to the Gillmans. They were:

- Florence Esther (b.1861). Joined Josephites in Penola, South Australia. Ordained in 1887. Died in Kensington SA, in 1949.

- Kate Anna (b.1862). Died in Bunbury in 1864, aged two years.

- Mary Emma (b.1864). Married Jacques Maurice Artaud. Died in Melbourne, in 1959.

- Edward William Henry Gillman (b.1865). Married under the name Edward WH Jones, to (1) Unknown. (2) Margaret Macbrien. Died in Albury, NSW, in 1942.

- Laura Lisette (b.1867). Died in Bunbury in 1868, aged 11 months.

- Rose Henrietta (b.1869). Joined Josephites in Penola, South Australia. Ordained in 1889. Died Kensington, SA, in 1956.

- Amy Ada (b.1870). Married Spiro Turner in Melbourne, 1897. Died in Melbourne in 1950.

- It is likely that all of the Gillman children received their education within the Catholic school system. In 1869 Florence won a prize as a 2nd class (Junior) pupil, for a distinction in Christian Doctrine, at the Annual Examination held at the Sisters of Mercy Convent in Perth.[71]

Two of the Gillman daughters, Florence and Rose, joined the Catholic Order of the Sisters of St Joseph, formed in 1866 in Penola, South Australia. [The Order has recently earned fame through its founder, Sister Mary McKillop, being canonised as Australia’s first saint in 2010.] It is of interest that the two young women were registered within the organisation under the surname ‘Gillman-Jones’.

FLORENCE ESTHER GILLMAN

Florence, the oldest daughter, left WA for South Australia in 1885, with the aim of entering religious life with the Sisters of St Joseph in Kensington. She professed her vows on 9 April 1887, adopting the name of Sister Mary Aelred of the Sacred Heart.[72] Their records show that Sister Aeldred spent the years from 1906-1920 back in Western Australia. During that period she was possibly based in Southern Cross, where a convent and school were opened in 1906, although she was not listed as one of the first group of four nuns who went there. In 1913 it was reported that the pupils at the Southern Cross Convent in WA had achieved high marks in a musical examination, with credit going to ‘Sister Mary Aelred, of the local Convent, to whom a very large share of the success of her pupils is due, is a teacher of high attainment in the musical arena. We offer her many congratulations.’ [73]

Sister Mary Aelred was a teacher who worked tirelessly in her chosen life and was described after her death in 1949, at the age of 87 years, as follows:

The late Sister Aelred spent sixty-three years in Religion, having been one of the pioneer members of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph. For her gentle disposition and her kindly ways she was loved and respected by all who knew her.[74]

ROSE HENRIETTA GILLMAN

Ordained as Sister Mary Gabriel, she was a teacher within the same Order. Rose entered religious life on 4 March, 1888 and her ordination took place in 1889.[75] Like her sister Florence, Sister Mary Gabriel also reached 87 years of age by the time of her death in 1956. They both passed away at the Kensington Convent and were buried at the Mitcham Cemetery. Sister Mary Gabriel’s obituary reads as follows:

Born Rose Henrietta GILLMAN-JONES c1869 in Bunbury WA

Teaching Sister

Died 18 May 1956 at St. Joseph’s Convent, Kensington

Aged 87 years

Cause of death Myocardial Failure 4 weeks. Artheriosclerosis many years. Carcinoma of Breast 15 years.

Buried Mitcham Order of St. Joseph’s Lawn Cemetery.[76]

…………………………………………………………..

The other two Gillman sisters married and led comfortable lives. Both retained a strong Catholic faith throughout their lives.

ADA AMY GILLMAN

Ada married Spiro Turner in 1897 in Victoria, under the maiden name of Ada Amy Jones. As a young man Spiro had a keen interest in the new sport of bicycle racing. Along with his brother he set up a business selling bicycles, first of all in Melbourne, where he advertised that he would soon return from England with 200 bicycles, which would be offered for sale at the firm of Turner and Turner in Elizabeth Street. [77] For a few years Spiro ran a bicycle business in Perth, WA, with a branch agency in Northam. His wife Ada joined him in WA in 1902 and they were living at West Leederville. They left the State in 1905. By 1908 he was in South Australia where the brothers were selling bicycles and then opened the Olympia Rink in Adelaide, catering for the latest craze of roller skating. In 1909 a skating carnival was held, with Spiro Turner acting as MC, and ‘an exhibition of waltzing was given by Mr. Woods (local manager), and Mrs. Turner.’[78]

This business was sold in 1909 and we find Spiro Turner and his family in NSW, where in 1910 he was advertising his newly-constructed skating rink at Newtown near Sydney. In 1913 the family was living at Milson’s Pt. in Sydney.

Ada Turner had two sons born in NSW, with Victor, born in 1905 at Cremorne and Samuel Verdun, born at Mosman in 1916. Both were educated at Catholic schools.

Amy Turner, 1921.[79]

In 1922 the Turners moved from NSW to St Kilda in Melbourne, where Mrs Spiro Turner was active at charity events, etc, frequently appearing in the social columns, with descriptions of her clothes. In 1925 the family’s address was 124 Marine Parade, Balaclava, near St Kilda.

In 1928 we read that ‘Mrs Spiro Turner, whose flared frock of vivid phlox pink georgette had a yoke closely studded with diamente’, was present at a dance held on behalf of the Past Pupils’ Association of the Convent of Mercy in Geelong.[80]

Their son Victor travelled to Ireland to train as a priest, with his mother Amy travelling there in 1936 to witness his ordination. As Father Victor H. Turner, he served as a Jesuit Army chaplain in WW2, being incarcerated for 3½ years at Rabaul by the Japanese.

Spiro Turner, aged 74, passed away in 1941 and was buried at the New Cheltenham Cemetery. Amy A Turner, aged 78, was buried there on 17 June 1950. Their son Samuel was killed in 1950 at the age of 34, after a fire caused a collapse of Selfridge’s Store in Liverpool Street, Sydney, where Samuel worked as a department manager.[81] He, too, was buried at the New Cheltenham Cemetery.

………………………………………………………….

MARY EMMA GILLMAN

The remaining Gillman sister, Mary Emma, born in Bunbury WA on 31 March 1864, married a Frenchman named Jacques Maurice Artaud. Her husband, known as ‘Maurice’, operated a business in Melbourne where he manufactured straw hats. The Artauds lived comfortably in the suburbs of St Kilda and Toorak, where they raised two daughters, Adele and Reneé, and two sons, Serge Maurice and Auguste Henri, who together operated a station property known as ‘Goombargalia’, in New South Wales.

Known as ‘Madame Artaud’, Mary’s name was frequently mentioned in the local papers, often associated with various fundraising events. As was the custom in those days, women’s dresses were described at these social events, with Mary’s taste for the latest fashions recorded in terms such as ‘a black tulle gown gleaming with jet and sequins’ (1923).

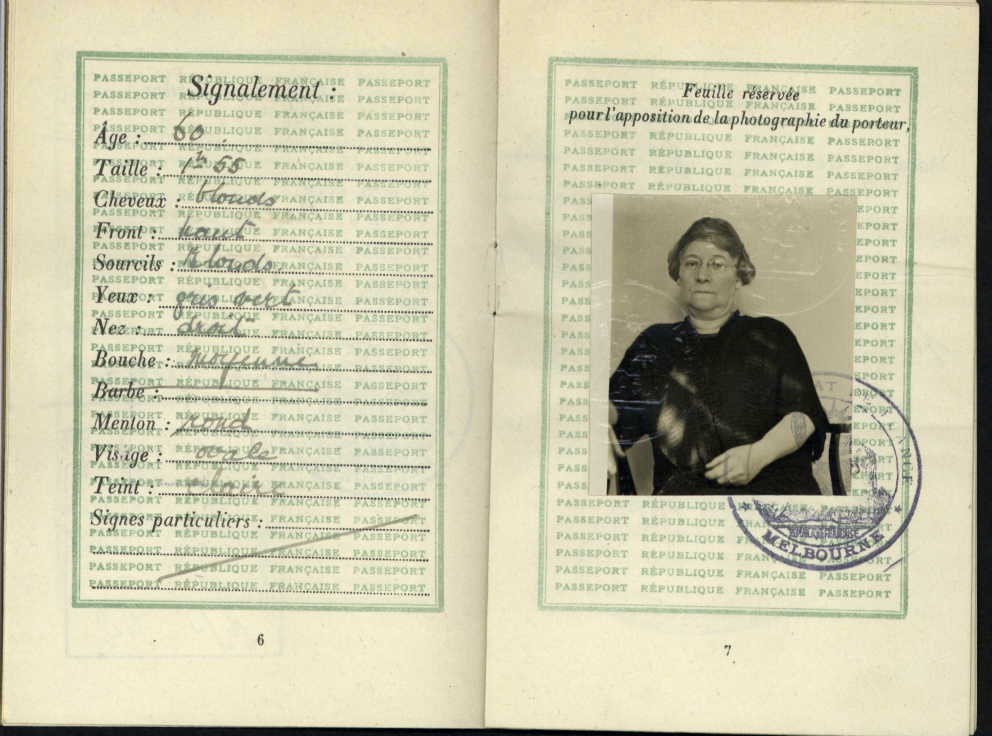

Mary Artaud was a skilled fundraiser for numerous charities. During WW1 she came to the fore, raising funds for the war effort. In 1919 she received the Medal of Reconnaissance Francaise from the French Government, in recognition of her sterling work in fundraising for the French Red Cross. The Artauds travelled to France in 1887 and in 1924. Madame Artaud’s French passport, issued in 1924 by the French Consul in Melbourne, conferred French nationality and permitted her to travel to France in with her two daughters.[82] It is of interest that in 1942 Mary had her French citizenship revoked, in favour of an Australian one.[83]

Mary Artaud’s French passport, issued in 1924.

……………………………………………………………..

EDWARD WILLIAM HENRY GILLMAN, the only son of Henry and Annastasia Gillman, was born in 1865 in Bunbury WA. Little is known about his childhood years, when the family moved from Bunbury to Busselton and Fremantle, but it is presumed that he would have received his education at Catholic Schools. After leaving school he probably worked in his father’s businesses and can be found in shipping lists travelling up and down the WA coast, sometimes in the company of his father. When his father Henry Gillman’s businesses failed he decided to leave WA and travelled to Melbourne in 1887. Edward accompanied him, leaving Mrs Gillman and three of the girls to join them in 1888. Florence has already gone to South Australia in 1885.

Edward Gillman was working as a salesman at a large furniture emporium owned by Abe Nathan in Albury, NSW, in 1913, using the name ‘Edward Jones’. He remained in that town until his death in 1942. He had two marriages, first wife unknown, and second wife Margaret Macbrian (sic Macbrien), whom he married in Goulburn in 1916 under the name Edward William Henry Jones.

Edward passed away in 1942. His obituary tells us that he left behind three children, Harry from his first marriage, and Rosie and Margaret from the second. The names of his four surviving sisters also appear in the obituary.[84] Edward’s daughter Margaret was an adopted child.[85]

Grave of Edward William Henry Jones (Gillman) and wife Margaret, Albury Cemetery.[86]

………………………………………………………………

(2) STEPHEN STOUT (1831 – 1886)

By Irma Walter, 2019

Stephen Stout was born in 1831 in France, to English parents Kedgwin and Mary Stout. When Stephen was around 14 years of age, the family returned to England, where his father took up an appointment as stationmaster at Waterbeach in Cambridgeshire.

Stephen and his brother went to London looking for work and over the next few years he had a range of employments. He was soon in trouble with the law when he was arrested for embezzling small sums of money from his employer at Camden Station in 1950. He was twice acquitted of these charges, but it wasn’t long before he re-offended, this time for cheating a customer when employed at one of the new telegraph offices. For this crime he was sentenced in 1851 to 12 months in Coventry Gaol.

In 1853 he married a dressmaker, Sarah Ann Barlow, and soon afterwards their son Stephen William Kedgwin Stout was born. Stephen wasn’t ready for the responsibility of marriage and fatherhood, falling into bad company and causing distress to his wife and her family. In 1856 he was arrested for forging his employer’s signature on a bank slip and falsifying the sale of a sewing machine. When in the Court he was described as ‘a showily dressed young man, suspected of dishonesty on several occasions.’

Unknown to his family at the time, Stephen’s life was made more complicated by the fact that in 1855 when he was employed by the committee of the English exhibitors at the Great Paris Exhibition for several months, he had an affair in Paris with a lady named Pauline de Lavarenne, whom he had secretly brought back to England, pregnant, and installed her in accommodation at Deptford.

The judge deemed him to be a danger to the community and sentenced him to 14 years’ transportation to Western Australia. Stephen spent time in Millbank Prison, then Pentonville, before being transferred to Dartmoor Prison to await transportation. In the meantime, Pauline had given birth to a son Kedgwin Stout. It is likely that Stephen never saw the boy.

Once on board the Lord Raglan and on his way to Western Australia, he was determined to make the best of his situation. His record shows that he took charge of producing an onboard newspaper, gave talks to the other convicts on a diverse range of subjects, and assisted the Rev. Frederick Lynch with teaching the other convicts basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills. He was considered a model prisoner.

The Lord Raglan arrived at Fremantle on 1 June 1858. After a brief period spent in Fremantle Prison, Stephen was sent to the Convict Depot at Bunbury, where he soon ingratiated himself with the Superintendent, Henry Duval, who appointed him as clerk and writer in the Depot. It wasn’t long before Stephen was giving talks and evening classes to the other prisoners, who were mostly employed during the day in roadmaking around Bunbury, a small port in the South-west.

One evening some local dignitaries were invited to the Convict Depot to hear one of Stephen’s talks, and soon after he was offered a position as teacher at Australind, a struggling settlement just a few miles north of Bunbury. As soon as he obtained his ticket-of-leave he went there as a replacement for another convict teacher, Henry Gillman, who had quit the post after a few months and set up a general store in Bunbury. Marshall Waller Clifton, Chief Commissioner of the settlement at Australind, was pleased to find a well-educated young man to fill the position. A classroom was set up in a small storeroom at the proposed townsite, and parents welcomed Stephen into their midst. He was a popular teacher, arranging a picnic and boat trip up the river for his pupils, assisted by some local ladies, who were impressed by this young man who spoke fluent French as well as English. Everyone was pleased with the results of an oral examination which was held at the end of the year at the tiny St Nicholas Church, due to the Australind classroom being too small to accommodate the pupils and their parents. At its conclusion those present enjoyed plum cake and tea.

All went well until Clifton heard of plans for Stephen Stout to marry a 15-year-old girl at the settlement. He called the girl’s father in for a talk, expressing his concern about her age. When Governor Kennedy heard of the affair and learned something of Stephen’s marital background, he sent word to George Eliot, Resident Magistrate of Bunbury, to get Stout out of the district. Stephen sent a pleading letter to the Governor, denying that he was already married, but to no avail. He soon found himself back in Fremantle.

Stephen set up his own private school there, naming it the Fremantle Academy for Boys. He offered a classical education, with subjects including penmanship, philosophy, book-keeping and languages. However the school didn’t last long in a cash-strapped society, where parents of large families needed their boys to be out earning a living instead of learning Latin and French.

Undaunted, Stephen set up a photography business in Fremantle. He was one of the Colony’s early photographers, producing carte-de-visite sized portraits and travelling around country areas taking photographs of people’s homes and business premises. People were keen to obtain these images in order to send them home to their families in England.

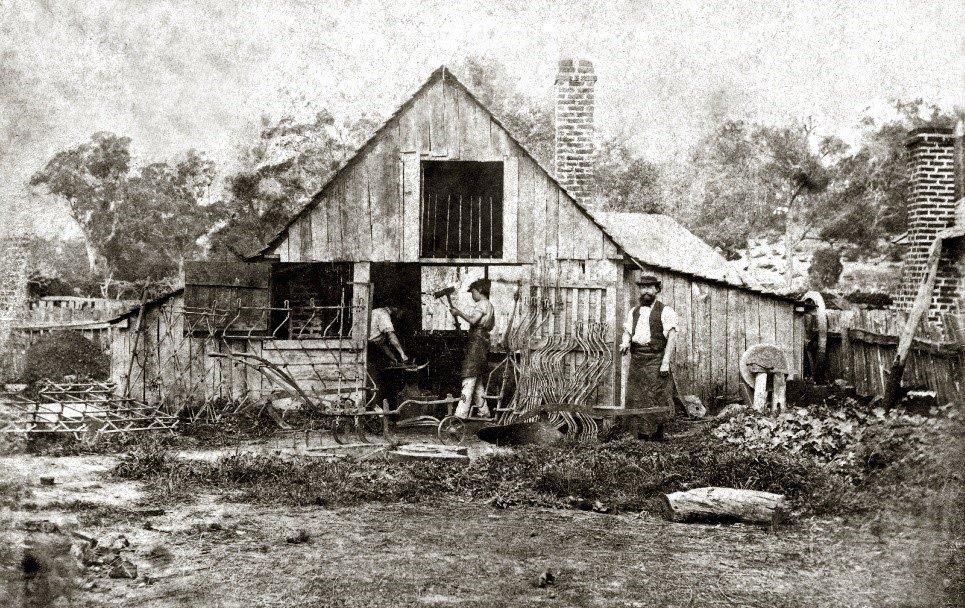

Anthony Keen’s Blacksmith’s Shop, Stephen Street, Bunbury, 1867. Photo by Stephen Stout, 1867, courtesy of the Treen family.

While back in Bunbury taking photographs in 1867, another young woman took Stephen’s fancy. She was Elinor Brown, step-daughter of Nathanial Howell, a prominent Perth lawyer. Elinor’s father, Sergeant Alexander Brown of the 99th Regiment, had died suddenly in 1851, soon after Elinor’s birth, while her mother ‘Fanny’ had died of tuberculosis after her marriage to Howell. Stephen decided to set up a private academy for boys in Bunbury. His school, the Wellington Academy, was situated in a two-story building in Victoria Street owned by the John Scott family, and attracted the sons of local businessmen and farmers.

For a while life was good for the couple, who were married in 1868 by the Rev. Andrew Buchanan at the tiny Australind Church. Stephen took part in the first concert given in the new Mechanic’s Institute, the first of many performances given by him over the years. In an article probably written by Stout himself as the local correspondent for a Perth newspaper, his humorous reading on the night was described as ‘giving every satisfaction’, while his song ‘Lord Lovel’, sung in character, was a great success.

In 1870 Stephen and Elinor, along with their first child William, went off to Perth in search of better prospects, leaving the Wellington Academy in the hands of another ex-convict, Archibald Cole. Over the next few years the pattern of opening and closing schools continued, with photography as the fall-back position. For a brief period in 1872 he set up a small newspaper, along with an ex-convict partner, but this ended in conflict and shut down soon after.

Stephen was lucky to obtain the post of Government Schoolmaster at the Pensioner Guard Barracks in Perth, holding this position from 1873 until 1878. His wife Elinor was employed part-time as his assistant, teaching needlework. This was a happy period for the family, with Stephen’s drinking problem held at bay by his membership of the Good Templars’ Society, one of many groups set up as a means of overcoming the scourge of alcohol consumption in the Colony. Stephen enjoyed popularity as head of his own Lodge, the ‘Rose of Perth’, addressing meetings on the subject of the evils of drink, and organising fundraising concerts, which were well-attended. His success and arrogant demeanour led to rivalries within the Good Templars movement and frequent disparaging references to Stephen’s character appeared in the local newspapers, due to what these days might be called ‘the tall poppy syndrome’.

The ‘Rose of Perth’ lodge shut down and around the same time Stephen learned that the Pensioner Barracks School was soon to close. After applying unsuccessfully for other Government positions, he was forced to accept another teaching post, as headmaster of the Geraldton State School. Teachers were poorly paid in those days and their work conditions were generally poor. In Geraldton he was teaching alongside Miss Strappini who was in charge of the infants and the girls. Once again, Stephen settled quickly into the social life of the town, becoming a member of the Working Men’s Institute, a group mainly made up of local businessmen. As a committee member he helped organise various entertainments. One of the members was Isaac Walker, with whom he combined to form the town’s first newspaper which they named the Victorian Express.

The newspaper was launched with great fanfare and high hopes for its future were predicted. It wasn’t long however before disputes between the partners occurred, with reports that its editor Stephen Stout was once again drinking heavily. This sometimes led to the late publication of the newspaper, which caused inconvenience to its advertisers and readers.

Walker was determined to get rid of Stout, and a much-publicised series of court cases were concocted against him. The first case involved the charge of embezzling two sums of 5/- from the business, for which Resident Magistrate George Eliot (formerly of Bunbury) set bail at the unheard-of amount of £1,200, the reason being that Stout might abscond from the Colony.

Stephen was found not guilty but was soon back in the Geraldton Court on a second charge, of stealing a bundle of old newspapers from the office and allowing his daughters to trade them at a local store for a few yards of calico. Once again the case was dismissed. A third charge by Walker against Stout on the grounds of poor book-keeping was also over-turned. Stephen was said to have doffed his white bell-topper hat on his way out of the Court, saying to his supporters, “That’s how it’s done, boys!”, a remark that did not go down well with his detractors, of whom there were many.

Stephen Montague Stout, journalist, c1880.

Another Geraldton businessman named Henry Gray, a somewhat controversial character, came to his rescue, with an offer to set up a rival newspaper, with Stout as editor. The Observer opened in 1880, but within a year it had not made a profit. The town was not big enough to support two newspapers and the new editor of the Victorian Express was waging a constant battle against the Observer through his columns. Gray was soon advertising for another editor, this time ‘one who didn’t drink to excess’, but the paper closed permanently.

Meanwhile in Perth the Stirling Bros. of the Inquirer newspaper, were looking for an experienced editor to take over the helm of their new paper, the Daily News and offered Stout the job of editor. In 1882 Stephen took passage on the first ship out of Geraldton, followed by his wife and children. They settled into a comfortable house in Roe Street in Perth and the children were enrolled in classes. All went well for a short time until Stephen had a falling out with Horace Stirling, probably over his drinking habits, and was sacked.

From then on it was all downhill for the family. Elinor, like her mother, finally succumbed to tuberculosis, a common ailment in those days. She died at the age of 38 years in 1885, leaving Stephen with six children. He could no longer find permanent employment and relied on intermittent payment for articles that he submitted to various local and Eastern States publications.

His children, ranging in age from two and fourteen years, were orphaned when in 1886 Stephen Stout collapsed and died suddenly on the footpath outside the Perth Hospital. Several of them were placed in the Girls’ Orphanage, while the youngest was taken into the care of two single sisters, Sarah and Agnes Cave. The two eldest boys were left to their own resources, one being arrested later for stealing from a boat while camped on the Swan River foreshore.

Newspapers around Australia reported Stephen Stout’s death, described by one editor as an ‘old penny-a-liner’. He was a talented, self-assured character, untrustworthy at times, who wasted the opportunities he was given, leaving his children penniless and homeless after his death.

[Further reading: Irma Walter, Stout Hearted, The Story of Stephen Montague Stout, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, WA, 2014.]

…………………………………………………………………

(3) JOSEPH FARRELL (1828 – ?)

Joseph Farrell, convict number 4143, arrived in Western Australia on board the Runnymede on 11 September 1856. Nothing is known of his background, apart from him being a single Protestant with a birth date of 1828, sent from Portsmouth Prison. He was a clerk with good reading and writing skills.[87] In the 1851 census he was recorded as a visitor in the Parish of St George in the East, in the borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. The record shows that he was a 22-year-old clerk, born at Epsom in Surrey and employed in the Bank of England.

Joseph had faced trial in 1854 at the Central Criminal Court in London on a charge of embezzlement, described by the Judge as ‘a very dangerous offence’, and was sentenced to 15 years’ penal servitude.[88] Crimes committed against the financial system were severely punished in those days.

During his trial Joseph Farrell (Farrall), aged 26, was described as a young man of gentlemanly appearance, employed as a clerk at the Bank of England where he committed the crime. Two others were charged with aiding, assisting and harbouring a felon, when he absconded after being accused of stealing a dividend warrant for the payment of £291. 7s. 8d., by forging a signature.[89] At the time there were said to be several other indictments against him.

While on the run from the police, a £200 reward was offered for information about his whereabouts. At the time a detailed description was widely distributed:

‘… about 25 years of age, about 5’5” high, has light brown hair, a ruddy complexion, has no whiskers, is rather stoutly built, and has a downcast look. He is in the habit of dressing in the sporting style – viz., in a Newmarket-cut coat, long waistcoat, and trousers made to fit tightly to the leg; usually wore a narrow flat-brimmed hat. At the time of his absconding, he wore a grey-coloured cap with peak, and grey-coloured coarse-mixture overcoat. He took with him a carpet-bag, and middle-size brown leather portmanteau, which have been recovered. Since he absconded, he has purchased a drab felt jerry hat, a pair of black moleskin trousers, with narrow blue stripes down them, and a cotton handkerchief of a dull red colour. He also has with him a pair of drab leggings.[90]

The newspaper notice cautioned the public against negotiating two bank notes (numbers given), to the value of £500 each. The notice was signed by the Superintendent of City Police, London, March 7, 1853.[91]

Farrell gave himself up and pleaded guilty of having forged certain dividend warrants, in the name of a Dr. Davidson. Following his trial he was committed to Newgate Prison.[92]

In WA his conduct chart between October 1856 and June 1858 shows his behaviour as V. Good / Excellent.[93] He was sent to the Bunbury Depot on 9 March 1861 and received his ticket-of-leave on 31 August 1858 at Bunbury.[94] He was employed as schoolmaster at Australind between 1861 and 1864.

Joseph’s life from that time is unknown. There is no record of further convictions. It is possible that he left the Colony.

PARKFIELD SCHOOL

(1) GEORGE NEWBY WARDELL (1828 – 1905)

In 1869 convict George Newby Wardell was appointed as the first teacher at Parkfield School in Australind, employed to teach the five sons of farmer Robert Henry Rose of ‘Parkfield’. Mrs Rose recorded in her diary on Tuesday 16 April that Wardell had called in and offered his services as a teacher. Due to the shortage of available teachers in the colony, she was pleased to engage him and asked him to commence as soon as things were ready. It is thought that Wardell at that time was working as a labourer at Ben Piggott’s nearby ‘Springhill’ property.[95] A letter to Rev. Joseph Withers seems to suggest however, that Wardell was transferred over from his previous employment as teacher at Capel School.[96]

Robert Rose set his men to work, converting an existing building, presumably a former workman’s cottage, into a schoolroom. On 17 April Rose noted in his diary that a workman Thomas was preparing the schoolroom, and that a week later was putting down the flooring. In May, the Rev. Buchanan was able to conduct the first church service in the building, and Thomas was making desks for the pupils. The room was whitewashed before the school opened on 8 June. Work continued on the building, with Thomas putting some shingles on the roof. In June the following year, more work was carried out, with windows put in, a chimney installed, and shingling of the roof was completed.[97]

George Wardell had previously been employed as the first teacher at the school in Capel in 1868, although the Bunbury Education Committee had been warned by the General Board of Education that ‘reports of Wardell’s intemperate habits were known, and that he should be carefully watched’.[98]

Wardell did not remain at the Parkfield School for long, returning to his previous employment at Ben Piggott’s ‘Springhill’ property. The reason for him leaving the school is not known. He was replaced at Parkfield by another ex-convict, Adolph Hecht, in January 1871.[99] Hecht, too, didn’t stay long, leaving at the end of that year, after complaining about the state of the school building. George Wardell was called on once again to open the school on 22 January 1872. [100] Having gained his freedom a few months later, Wardell resigned with the intention of going to Victoria. He was briefly replaced at the school by local farmer William Reading on 15 April, who in turn was replaced by another convict, Daniel McConnell, who remained there until April, 1875.[101]

BACKGROUND HISTORY

George was not a typical class of convict, coming from a privileged background. He was the eldest child born in 1828 to Rev. Henry Wardell and his wife Mary (née Newby). Henry Wardell was the first Rector of St Paul’s Parish Church, built in 1828 in Winlaton, a village in the county of Durham.[102] The patron of the Church was the Bishop of Durham. It was a prosperous parish and the living was valued at £356 in 1835. Henry Wardell bore the cost of building the first rectory there and held the position until his death in 1885, at the age of 84 years. Headstones for Henry and his wife Mary (who died in 1868) are in the church graveyard. There is also a stained-glass window in the Church, commemorating Mary’s life.

St Paul’s Church of England, Winlaton was designed by Ignatius Bonomi and built in 1828.[103]

The children of Henry Wardell and his wife Mary were as follows:

George Newby, born 1828.

Henry John, born 1830.

Charles Reed Blackett, born 1832.

Mary, born 1833.

Mark William, born 1834.

Mark Newby, born 1835.

William Henry, born 1837.

Charles Clavering, born 1838.

[The youngest son, Charles Clavering Wardell, is of interest because of his connections to the most famous stage actress of that time, Ellen Terry. Charles was educated at the distinguished Rossall Boarding School in Lancashire. On leaving school he received a commission in the 66th Berkshire Regiment, before deciding that acting was his preferred career. He became a well-known actor, performing under the stage name of ‘Charles Kelly’ in some of the famous theatres in England. Charles also worked as a journalist. For some years he was the husband of the famous British actress Ellen Terry, who during a turbulent career had a number of partners and husbands. Her career lasted almost seven decades. Charles died in 1885, aged 46.[104]]

Another of Henry’s sons, Henry John Wardell, born 1830, was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1854.[105]

A FOOLISH CRIME WITH SERIOUS CONSEQUENCES

George Newby Wardell, the eldest son, born in 1828, also received a good education, at Sedburgh School in Cumbria.[106] His marriage to Margueretta Popsay Smith (born Greenwich to Henry & Hannah Smith in 1831) took place in 1850. They lived an insecure existence, with multiple places of residence over the next few years. George gained some qualifications as a solicitor, and in 1853 was a partner in a firm in Leicester Square when the partnership was dissolved.[107] Another partnership was dissolved the following year. He was in gaol as an insolvent bankrupt in 1854.[108] In 1858 one of his partners in a firm of Attorneys-at-law was arrested for bankruptcy and in 1860 George was back in gaol as a bankrupt, following a court case against him as an insolvent attorney in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1859:

ORDERS have been made, vesting in the Provisional Assignee the Estates and Effects of the following Persons: On their own Petitions.

COURT FOR RELIEF OF INSOLVENT DEBTORS. The 16th day of June, 1860.

George Newby Wardell, late of Marlborough-street, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Attorney-at Law was in the Gaol at Newcastle-on Tyne.[109]

In 1862 George Newby Wardell, attorney, son of the Rev. H. Wardell, of Winlaton, Durham, was arrested in Clitheroe, Manchester, charged with forging and uttering a cheque to the value of £4/10/-, by falsifying the signature of a former school friend, the Rev. Reginald Remington. He was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude.[110]

George Newby Wardell (Reg. Convict No. 7584) was transported to Western Australia in the Lord Dalhousie in 1863. He received his ticket-of-leave on 2 November 1864, and his conditional pardon on 5 October 1867, when he was employed at Capel. In 1868 he was appointed as the first teacher at the new Capel School. Wardell does not appear to have held this position for long, because he is recorded as employed at Ben Piggott’s property ‘Springhill’ at Australind, when he visited the neighbouring property ‘Parkfield’, and offered his services as a teacher.

From 1851, passages were offered to the wives and families of ticket-of-leave men in Western Australia, as a means of overcoming the serious shortage of females in the colony. The proposed cost of a passage was £15, with half-fares for children, on the proviso that the sum would eventually be re-paid by the convict.[111] The take-up of this scheme was initially slow, as there was reluctance on the part of some wives to join partners who had brought disgrace upon the family. On the other hand, many of the convicts had formed new relationships with women in the colony, or did not want to burden themselves with wives and children to support.