CONSPIRACY TO MURDER THE GOVERNOR of the BRISTOL GAOL. – Some sensation has been created during these assizes by the discovery of a conspiracy formed among some of the Bristol prisoners, to murder the governor, Mr. Gardner, on his return with them from Gloucester to Bristol. Previous to leaving the gaol at Bristol the prisoners had all been strictly searched, to see that they had nothing about them. On their arrival at Gloucester, and while the prisoners were awaiting their trial, one of them sent for Mr. Gardner, and said he should not like to see him injured, and then disclosed the plan which had been formed by some of the prisoners (three of whom were ticket-of-leave men) to murder him. He said that Thomas Vowles (a ticket-of-leave man) had a stone about his person, with which he intended to kill the governor on the return journey to Bristol, in case he (Vowles) should be convicted. He said that Vowles thought that by so doing he would be able to obtain possession of the keys of the handcuffs, and so let the prisoners go, and that two others of the prisoners were in the plot. Vowles was then searched, and a large stone was found upon him, which he must have managed to secure while passing through the court-yard of the gaol at Bristol, where some building was going on. Vowles pleaded guilty to a charge of burglary, committed in conjunction with his father. Mr. Baron Bramwell, before passing sentence, examined Mr. Gardner upon the facts above stated, and then sentenced the prisoner to be transported for life.[1]

The others involved in the plot were Charles Jenkins, real name Charles Vowles (a relative of Thomas, perhaps?), and an Irishman named Michael O’Brien (or O’Brian). Their connection to the crime of conspiracy to murder can be found in the British prison records. Each has a note attached to their record, confirming their involvement. All three men were transported to Western Australia onboard the Lord Raglan, arriving on 1 June 1858.

……………………………………………….

Thomas Vowles (c1837 – ?) (Reg. No. 4565)

At the time of the 1841 Census, Thomas Vowles, aged 4, was living at Temple Back, District 16, Temple, in Gloucestershire, along with his father Job Vowles, aged 29, and his mother Sarah, aged 25. They were all born in Gloucestershire.

Just before Christmas in 1850 Thomas Vowles (aged 15) was charged with stealing £10 from the till of the bar at the Saracen’s Head in Temple Gate. He gave one pound to his associate George Jones, and spent most of the money on treats for Christmas, including oranges, lemons, cocoa-nuts, herrings, pickled cabbages, figs, glasses and beer, and a large plum pudding, which were later found at his parents’ home. Thomas had hidden the balance of the money in his mother’s wash-house. His parents denied knowledge of where the goods had come from, saying that they thought the money had come from some work Thomas had done for a local farmer. His father Job Vowles described himself as a labouring man, who worked occasionally at a brewery.[2] Thomas was sentenced to a term of nine months on 29 March 1851 at the Gloucester Assizes.[3]

In February 1852 Thomas was labelled ‘an incorrigible little vagabond, when he stole a piece of bacon from a shop, displaying the coolest hardihood of demeanor when he was sentenced to six weeks’ hard labour, with the piquant addition of a whipping’.[4]

This did not deter him. In July 1852 he entered a warehouse and stole clothing and other articles. This time he was sentenced to seven years, released early on licence on 6 September 1856.[5] He was described as Thomas Vowles, aged 15, height 5’1”, with light brown hair, blue eyes, light complexion and small in stature. He spent time in Bristol and Millbank Prisons, then at Parkhurst Prison for boys on the Isle of Wight from 4 October 1852, before being sent to Portland on 5 March 1856.[6] In Thomas’s record his father was listed in the records as Thomas (?) Vowles, of 6 Matilda Place, Baptist Mill, Bristol.[7]

Soon after his release, young Thomas’s name appeared in the newspapers again, along with his father Job Vowles. Described as two ticket-of-leave men, they were apprehended when the older man tried to sell some battered silver. The dealer became suspicious and asked him to come back in half an hour and meanwhile called for a policeman. Job and his son Thomas were found loitering nearby, and more stolen goods were found at their lodgings. They faced trial at the next Gloucester Assizes.[8] Both pleaded guilty to the robbery. Job was gaoled for one week for receiving the stolen goods, while Thomas had another more serious offence pending, that of conspiracy to murder JA Gardner, the Governor of Bristol Gaol.

In the Court, Mr Baron Bramwell closely examined Mr Gardner about the facts of the case, before sentencing Thomas Vowles to transportation for life.[9] [Some reports state that three others were in on the plot.[10] The names of two are revealed in convict records as Charles Jenkins (real name Charles Vowles), and Michael O’Brien (or O’Brian), with both receiving sentences of 15 years.[11]]

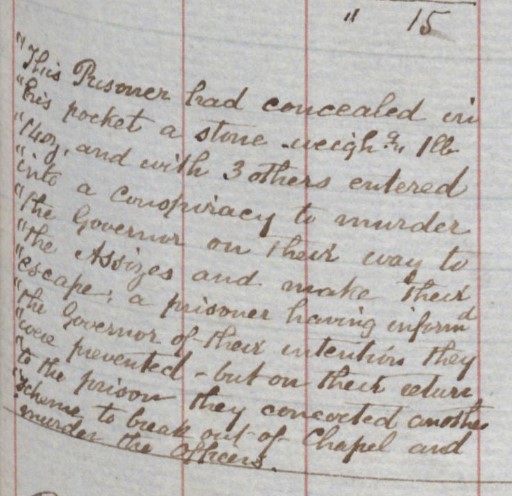

After receiving his life sentence on 23 November 1857, Thomas Vowles was taken from Gloucester Prison to Millbank, where his conduct was pronounced ‘Good’ while in Separate Confinement for 11 weeks and 4 days, but at Public Works –‘Bad’.[12] A special note on purple paper was attached to his Millbank Prison entry, as Prisoner No. 4013, – “Convict T. Vowles may be kept in Separate Confinement while at Millbank – See offence in his Caption Papers – Signed D. O’Brien.” A further hand-written note in his record went as follows – “This prisoner had concealed on his person a stone weighing 1lb 14 ozs, and with three others entered into a conspiracy to murder the Governor on their way to the Assizes and make their escape; a prisoner having informed the Governor of their intentions they were prevented – but on their return to the prison they concocted another scheme to break out of Chapel and murder the Officers.”[13] [See Appendices 1 & 2]

[An identical note on purple paper was attached to the next entry in the Millbank Journal, that of a Charles Jenkins, alias Charles Vowles, labourer, 26, whose father was John Vowles of Philip Street, Bedminster, in Bristol. Charles was another of the three conspirators said to be plotting to kill the Governor of Bristol Prison. A pencilled note was added – “Passed by D. Baly, but not sent to Port because the above prisoner was sent there. To go to Chatham.” This indicates a connection between the two, and a perceived need by prison authorities to keep them apart. This man Charles Vowles/Jenkins was transported for fifteen years for assaulting John Masters and stealing his watch.[14] He too was sent to Western Australia onboard the Lord Raglan, but under his alias ‘Charles Jenkins’ (Convict No. 4804). The family relationship between the two convicts needs to be checked. The hand-written note about the conspiracy was repeated on the record of a third man, Michael O’Brien.]

Thomas Vowles’ Record in WA

Thomas Vowles was received onboard the Lord Raglan from Portland Prison on 24 February 1858.[15] During the voyage to Western Australia he was recorded as a good scholar, able to read and write well, having previously attended both Day and Sunday Schools.[16]

The ship arrived at Fremantle on 1 June 1858. Thomas Vowles, a single man, aged 19, was described as a carpenter, 5’9”, with light red hair, blue eyes, a long face, a fresh complexion, of slight build, with a mole on his right arm.[17]

Despite the more moderate system of convict discipline in Western Australia, with early release on Ticket of Leave for good behaviour, Thomas Vowles’ relationship with the authorities was troublesome. From his previous record in England, it seems inevitable that he would attempt an escape from the Colony.

24/9/59 – Pro. Prisoner transferred to Toodyay Road Party.[18]

4/6/60 – Sentenced to 12 months for having a cart ch—-(?), the property of F Whitfield, Toodyay.

6/6/60 – Received from Toodyay.

16/6/60 – To Convict Establishment.

9/7/60 – Sentenced to three years and 100 lashes.

14/3/61 – To be released from Separate Confinement – any further mitigation of sentence must depend on their own conduct and industry.

24/6/61 – His Excellency has been pleased to sanction a remission of —-(?) out of the three years for attempting to escape – to be restored to Rob.(?) Class.

2/5/62 – Application premature. When his ordinary time and first Mag. Sentence is completed, with exemplary conduct his case may be again brought forward.

27/8/62 – Forfeit dinner.

8/9/62 – Petition.

25/9/62 – To be discharged.[19]

25/9/62 – Ticket of Leave.

14/10/62 – Discharged from hospital.[20]

31/12/62 – Carpenter, 6/- per day, Marshall & Co. High Street, Fremantle.

3/2/63 – Resident Magistrate Fremantle – Out after hours (on 24/12/62) – fined 5/-.

March ’63 – Escaped from Vasse District.

April ’63 – Supposed to have escaped in ship Merchantman.[21]

Absconding to the Eastern States

We next find Thomas Vowles (alias Thomas Smith) facing a charge in Victoria, in company with another absconder from WA, William Barton, (alias Mason, alias Phillips) —

CHARGES OF HOUSEBREAKING. — Thomas Smith, alias Vowles, and William Barton, known also under many aliases, were charged with housebreaking. There was a second charge against the prisoners, of being convicts absconded from Western Australia. Detective Williams said he had arrested the two prisoners the previous day upon the steamer Wonga Wonga, just leaving for Sydney. The prisoners were suspected of being the perpetrators of the hotel robberies so frequent in April last. When he arrested the prisoner Smith, as he was standing by the bulwarks of the vessel, he dropped a watch with Albert chain into the river. Witness had taken means to recover the watch. He read descriptions from documents received from Western Australia, making it appear that they were convicts illegally at large from that colony. Remanded for a week.[22]

[Note: No convict William Barton is listed in Western Australia. George Mason (Reg. No. 4820), who arrived on the Lord Raglan, was issued a Conditional Pardon in 1863. George Mason, alias ‘Chunkey (or Junkey) Philips’, alias ‘William Baker’, was convicted on 15 July 1856 at Dover for larceny. Due to previous convictions, he was sentenced to 14 years. In WA on 22 October 1860 he was convicted at the Vasse for indecency and sentenced to 18 months.[23]]

Absconders from Western Australia. — Thomas Smith and William Barton were charged, on remand, with being absconders from Western Australia. As there was not sufficient evidence to support that charge, they were remanded until the following day for the attendance of a person who was prosecutor in the charge of felony, on which one of them was convicted some years ago. A second charge against the prisoners, of burglary, on which they had been remanded several times, was withdrawn, as there was no evidence before the court to support it.[24]

ABSCONDERS FROM WESTERN AUSTRALIA.

At the City Police Court on Wednesday, Thomas Smith, and Wm. Barton, on remand, were charged by Detective Williams with being absconders from Western Australia; with being rogues and vagabonds; and with housebreaking. They had been apprehended some time ago, for being absconders, on board the Wonga Wonga, as she was about to sail for Sydney; but their luggage, which was stowed in the hold, could not then be secured. A carpet bag was discovered in the berth they were to have occupied, when the vessel arrived at Sydney, and in it there were found a quantity of housebreaking implements, and also a book which had been stolen from a private house, where one of them had been formerly residing. The first witness examined was a young lady named Jessie Cairncross, a schoolmistress at Williamstown. She deposed that the prisoner Smith came to her mother’s house to reside as a boarder on the 24th ult., and left several days afterwards. He then gave the name of Marshall. After he left witness missed a book from her bookcase, and that produced in court and which had been found in the prisoner’s carpet bag was the same. Some of the clothes, also found in the bag, she was certain she had seen him wear. The bag was also similar to that he had at the house. Mrs Owens, a boardinghouse-keeper in Lonsdale street, deposed that the prisoners stayed at her house several months ago, but she missed nothing after they left. She washed some linen for them during their stay at her house, but she could not swear whether that produced was the same. Mr Bushell, landlord of the Royal Oak Hotel, Swanston-street, deposed that the prisoners came to his house on the 21st ult., and asked to be accommodated with beds. They both went to bed about twelve o’clock. Witness shortly afterwards went to his room, and it was only with great difficulty that he could open the door. The lock was stiff, and he could hardly turn the key round. He lost nothing, and did not take any further notice of the circumstance, as the prisoners both left in the morning early. The next evening Smith returned by himself, and went to bed about midnight. Witness about one o’clock went up to his room, but he could not open his door at all, and at last he had to break it open. He then found that the bolt had been turned back, and, on taking off the lock on the following morning, he found the wards very much disarranged and scratched, as if with some sharp instrument. The prisoner having left at an early hour, he gave information to the police, as he felt certain that it was he who had been tampering with the lock. Mrs Bushell corroborated this evidence. This closed the case for the defence. Mr Read, who appeared for the prisoners, contended that the carpet bag might have been placed in the berth at Sydney by some other person, and that no evidence had been adduced to show that it was the property of the prisoners, or that the housebreaking implements that were in it belonged to them. Mr Sturt held that, though it had not been directly proved, yet it was sufficiently clear that the carpet bag had been left in the berth by the prisoners, both from the fact that it had not been claimed by any of the passengers on the arrival of the vessel at Sydney, and as the book was in it which had been stolen from the residence of Mrs Cairncross by the prisoner Smith. The charge of being rogues and vagabonds being thereby established, the prisoners were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, with hard labor. Mr Read gave notice of appeal. On the other charge of housebreaking, the prisoners were remanded.[25]

Thomas Smith, alias Vowles, housebreaking; Thos. Smith, alias Vowles, being an absconder from Western Australia; Wm. Barton, alias George Mason, alias Cranky, alias Junky Phillips, alias William Baker, being an absconder from Western Australia; remanded for seven days.[26]

Thomas Smith alias Vowels (sic), and Wm. Barton alias Phillips alias Mason, two escaped convicts from Western Australia, were sentenced at the Police Court, Melbourne, on Wednesday, to six months’ imprisonment each, for having in their possession housebreaking implements. They were also remanded on a charge of housebreaking.[27]

ABSCONDERS FROM WESTERN AUSTRALIA. Wm. Barton and Thomas Smith were brought up on this charge. They had been remanded from the previous day, for the evidence of a person named Merritt, who had been prosecutor in a charge of felony, on which Barton was convicted some years ago in England and transported. Mr Merritt deposed that, in the year 1848, as he was returning home from the Oaks races, he was robbed of his watch by a man who was afterwards arrested and convicted under the name of William Barton. The prisoner Barton had similar features to that man, and witness believed he was the same, but from the length of time since the robbery occurred he could not swear to him. Detective Martin said that he knew the prisoner at home by the name of Junky Phillips. Witness was not present at the trial, and therefore could not swear that he was the same Barton who was convicted for robbing the previous witness. There being no other evidence against either of the prisoners, the charge against them could not be sustained, and they were ordered to enter into their own recognisance of £20 to leave the colony in seven days. Having appealed against the sentence of six months’ imprisonment, which was a few days ago passed upon them, under the Vagrant Act, for having housebreaking implements in the carpet bag which was found in the berth they were to have occupied in the Wonga Wonga steamer, and which had been traced to their possession, they were ordered to find each one surety in the sum of £25 that they would appear in support of the appeal.[28]

The two men, Barton and Smith, who have for several weeks past been frequently remanded on various charges of being absconders from Western Australia, burglars and vagrants, were at length disposed of at the City Court on 23rd inst. Though well known as desperate characters and accomplished burglars, circumstances have enabled them to escape punishment for the present. It may be remembered that, several days ago, they were each sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, under the Vagrant Act, for having housebreaking implements in their possession. Against that decision they then gave notice of appeal. A second charge of burglary against them was, after repeated remands, withdrawn, as the proceeds of their villany had been carried to Sydney in the steamer, on board of which they were arrested, and could not be recovered, notwithstanding the efforts of the police. The third charge of being absconders from the penal settlement in Western Australia, remained, but, as there was not sufficient evidence to prove it, that charge also fell to the ground. Barton was transported in 1848, for robbing a man named Merritt of his watch, as he was returning from the Oaks races. Mr Merritt having some time ago emigrated to this colony, appeared in court on Wednesday but, from the length of time since the occurrence took place, he could not swear to the prisoner’s identity. The bench ordered both prisoners to enter into their own recognisances to leave the colony, and admitted them to bail in one surety of £25 each, pending the result of the appeal. The money was soon forthcoming; and, shortly after the decision of the court, they were both at large. It is not to be expected that they will answer the appeal, and there is every probability that they will, without delay, follow their luggage to Sydney.[29]

It seems that they were not returned to Western Australia, probably because they both had been issued their Conditional Pardons [This precluded them from returning to England.]. A notice was published on 4 July 1877 in the Victorian Police Gazette, copied from the WA Police Gazette that year regarding the escape of Vowles from Western Australia in 1863, (his name spelt there as Vowals and Vowalls) suggests that he had never been found —

Vowals (sic, Thomas, (4865), T/L, 9 March 1863 from Fremantle; slight, 38 years of age, 5’9” high, light red hair, black eyes, long visage, fresh complexion, mole on right arm.[30]

No more is known about either Thomas Vowles or William Barton.

…………………………………………………………………………………………

Michael O’Brien (c1820 – ?) (Reg. No. 4831)

Michael O’Brien was another of the conspirators who plotted to kill Governor Gardner of the Bristol Prison. Like Thomas Vowles and Charles Jenkins (real name Charles Vowles), a similar note was attached to his prison record — “This prisoner and others entered into a conspiracy to murder the Governor on their way to the Assizes and make their escape; a prisoner having informed the Governor of their intentions they were prevented – but on their return to the prison they concocted another scheme to break out of Chapel and murder the Officers.”[31]

This same note was attached on his record on arrival in Western Australia.[32]

Michael O’Brien was born in Ireland and made his way to England during the period of the great Irish famine. In 1856, at the age of 32, he committed a robbery with violence, in company with a John Gibbons. Together they assaulted and robbed a man named John Smith after he alighted from a train at Wednesbury Station to make his way home. O’Brien tapped him on the head and knocked him down. He ran off and Gibbons pretended concern for Smith, who recognised him as one of his attackers, invited him to a nearby pub to have an ale with him as a pretext, and called for a policeman to arrest him. His companion Michael O’Brien was later arrested at his lodging place, with two sovereigns and four half-crowns in his possession.[33] Together O’Brien and Gibbons were convicted of robbery in company with violence and were sentenced to six Calendar months.[34] On 4 December 1856 as Michael O’Brian, aged 32, he faced Court at Gloucester, and due to a previous conviction and felony [probably the charge of conspiracy to murder the prison Governor, though not mentioned], plus ‘Bad’ conduct, he was sentenced to 15 years’ transportation.[35]

His record in British prisons

Michael had previous convictions, one on 24 October 1850, for stealing lead at Bristol, which earned him six months in prison, and another on 4 January 1853 for stealing boots, sentenced to eight months hard labour.[36] Following his 1856 conviction, he stayed in Separate Confinement in Bristol Prison for one month & four days with his conduct recorded as ‘Bad’, before being sent to Millbank, where he served 10 months and 13 days in Separate Confinement, when his conduct was ‘Indifferent’. He was transferred to Portsmouth Prison on 2 November 1857, before being taken onboard the convict ship Lord Raglan. He was described as married with two children, his wife’s name recorded as Tilly O’Brian, of 7 Merchants Court, St Pauls, Bristol.[37]

His life in WA

Michael O’Brien arrived at Fremantle onboard the Lord Raglan on 1 June 1858, received from Millbank Prison. His record in Separate Confinement was ‘Indifferent’, and at Public Works ‘Bad’. He could read and write imperfectly.[38] He was described as aged 38, married with one child, his religion RC, height 5’6½”, with dark brown hair, dark hazel eyes, an oval face, dark complexion, and of stout build. He had a cut on his right eyebrow and a scar on his left thumb.[39]

Soon after his arrival Michael was taken to the Lunatic Asylum for observation.[40]

On 29/7/58 he was ‘given no dinner – Insane’.

On 28/9/58 he was sent to the L.A. (Lunatic Asylum).[41]

No more information has been found regarding Michael O’Brien/O’Brian.

………………………………………………………………..

Charles Jenkins (real name Charles Vowles) (Reg. No. 4804)

This man, along with Thomas Vowles and Michael O’Brien, was found guilty of conspiring to murder the Governor of Bristol Gaol. Like Michael O’Brien he was sentenced to be transported for fifteen years. However the records show that the reason given for the transportation of Charles Jenkins/Vowels (sic) for fifteen years was robbery with violence on 2 April 1856 and a pre-conviction.[42] He had been found guilty of assaulting John Masters and stealing his watch.[43]

His prison record includes the same note as Michael O’Brien –“This prisoner and others entered into a conspiracy to murder the Governor on their way to the Assizes and make their escape; a prisoner having informed the Governor of their intentions they were prevented – but on their return to the prison they concocted another scheme to break out of Chapel and murder the Officers.”[44]

Similar to the entry for his co-conspirator Thomas Vowles, a note on purple paper was attached to his entry in the Millbank Journal, listed as Charles Jenkins, alias Charles Vowles, labourer, 26. His father was recorded as John Vowles of Philip Street, Bedminster, in Bristol.

A pencilled note was added –“Passed by D. Baly, but not sent to Port because the above prisoner [Thomas Vowles] was sent there. To go to Chatham.” [This indicates a connection between the two men with the surname Vowles, and a perceived need by prison authorities to keep them apart.]

He was taken onboard the Lord Raglan, bound for Western Australia, but under his alias ‘Charles Jenkins’ (Convict No. 4804). Description, greengrocer, single, aged 29, height 5’9”, light brown hair, grey eyes, oval face, medium stout, no distinguishing marks.[45]

His record in WA

5/7/60 – Issued Ticket of Leave.

7/7/60 – Discharged on Ticket of Leave and passed from the Swan.

11/7/60 – Pass removed seven days.

27/7/60 – Reported engaged to Thomas Wilding at Northam, piece work.

27/1/63 – Granted his Conditional Pardon.[46]

8/11/67 – Charles Jenkins (Local Convict No. 1651, formerly 4804), aged 34 years, uttering a stolen money order, six months, JW Clifton, R.M.[47]

16/11/67 – C Jenkins, local, received at Fremantle Prison from Northam – six months.[48]

27/8/60 – Allowed 10 days’ pass to York to service of H Mead, Springhill.

27/7/70 – Date of Ticket of Leave, Toodyay.[49]

10/11/70 – Stealing spirits, 6 months, WJ Clifton, R.M., Northam. Release date 10 May1871.[50]

[Note: Charles Jenkins is said to have also spent time in the Champion Bay District. [See details on the Midwest Convict Register, at https://midwestwaheritage.com/ ]

In 1882 Charles Jenkins, together with Alexander Baillie and Patrick Dempsey, were arrested at Youngerup in the Kojonup District and committed for trial at Albany. The property was partially recovered. The three were found guilty of the larceny of sandalwood, the property of Alfred Quartermaine, and sentenced to 18 months.[51] A later entry has Alexander Baillie sentenced to 18 months, Charles Jenkins 12 months, and Patrick Dempsey was acquitted.[52] The following year Charles Jenkins was discharged at Kojonup, for want of prosecutor.[53] On 27 April 1887 he was arrested for stealing a tin of cow hock, the property of JM Flanaghan of Kojonup, but was discharged.[54]

It appears likely that Charles Jenkins (real name Charles Vowles), died alone in his tent at Northam —

Northam—A destitute old man named Jenkins, lately from the fields, died here on Sunday last from general exhaustion.[55]

Afterwards there was criticism of the method by which his body was conveyed to the Northam Cemetery —

Original Correspondence.

A PAUPER’S FUNERAL. TO THE EDITOR.

SIR,—One of the most ignoble, uncharitable and inhuman incidents that have ever come under my cognisance during the whole period of my life was that enacted in Northam on Monday last. I refer to the burial of an old and destitute man named Jenkins, who died somewhat suddenly on Sunday at his camp in the vicinity of the river. The facts of the case as reported to me in respect of this old man’s interment are simply such, if true, as to move all to compassion for the deceased and his relatives (if he has any), and indignation towards those who were responsible for its undertaking. It appears Jenkins’s caput mortuum were first conveyed to the local court house and there deposited (clothes, boots, and in fact everything but his hat and a couple of cakes of tobacco which a by-stander purloined) into a very seedy looking box, and thence into an equally disreputable looking one-horse dog cart, driven by two very dirty looking men, who comfortably ensconced on the rude and very much exposed coffin drove through the principal thoroughfares of the town en route for the burial ground.

Rattle his bones over the stones.

He’s only a pauper whom nobody owns.

Arrived at “God’s acre,” poor Jenkins was placed in his grave as unceremoniously as he was in his coffin, and without the last office of the dead being pronounced upon him. Sir, I am a comparative stranger to Western Australia and therefore ask if this is the usual way in which pauper funerals are conducted? Such a proceeding would not be tolerated in a decent, civilized community. Yours, &c.,

CIVIS.[56]

The following reference to Jenkins’ connection to Sturt’s survey party [of 1830] raises some doubts over its accuracy —

On Sunday last an old man named Jenkins was found dead in his tent, at Northam. He was an old identity, and was at one time connected with Sturt’s survey party. The cause of death was senile decay….[57]

……………………………………………………………………………

Appendices 1 & 2

[1] Hobart Town Mercury, 27 February 1857.

[2] Bristol Times and Mirror, 28 December 1850, & Exeter Flying Post, 2 January 1851.

[3] UK National Archives, Criminal Registers, Gloucester, Series HO27, Piece No. 96.

[4] Bristol Mercury, 28 February 1852.

[5] UK National Archives, Prison Registers, Series HO8, Piece No. 29.

[6] UK National Archives, Prison Registers, Parkhurst Prison, PCOM2, Piece No. 59.

[7] UK Prison Commission Records, Parkhurst Prison, Reg. of Prisoners, 1853-1869.

[8] Manchester Times, 1 November 1856.

[9] Dorset Country Chronicle, 18 December 1856.

[10] Leeds Mercury, 11 December 1856.

[11] UK National Archives, Prison Registers, Series PCOM2, Piece No. 38

[12] Convict Department, Character Book (R8)

[13] UK National Archives, Institution & Organisations, Prison Registers, Series PCOM2, Piece No. 38.

[14] Cheltenham Chronicle, 9 December 1856.

[15] UK National Archives. Prison Registers, Series HO8, Piece No. 135

[16] National Archives of the UK (TNA); Admiralty Transport Department, Surgeon Superintendents’ Journals of Convict Ships; Reference Number: MT32/1

[17] Convict Department, Estimates and Convict Lists, (128/1-32)

[18] Convict Establishment, Receipts & Discharges (RD3-RD4)

[19] Convict Department, Character Book (R8)

[20] Convict Establishment Medical – Daily Medical Journals (M19)

[21] Convict Department Registers, General Register (R1)

[22] Age, Melbourne, 29 August 1863.

[23] Convict Department Registers, (128/38-39)

[24] Age, Melbourne, 23 September 1863.

[25] Leader (Melbourne,) 19 September 1863.

[26] Age, (Melbourne), 29 August 1863.

[27] Star, (Ballarat, Victoria), 17 September 1863.

[28] Age, (Melbourne), 24 September 1863.

[29] Leader, Melbourne, 26 September 1863.

[30] Victorian Police Gazette, 4 July 1877.

[31] UK National Archives, Institution & Organisations, Prison Registers, Series PCOM2, Piece No. 38.

[32] Convict Department Registers, Character Book (R8)

[33] Wolverhampton Chronicle & Staffordshire Advertiser, 10 December 1856.

[34] Stafford Assizes, Staffordshire, Institutions and Organisations, Prison Registers, Series HO27, Piece No. 115.

[35] UK National Archives, Quarterly Returns of Prisoners, Prison Registers, Series HO8, Piece No. 135, Gloucester.

[36] Prison Registers, Portsmouth Prison, Hampshire, Series PCOM2, Piece No. 102.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Convict Department Registers, Convicts Transported on the Lord Raglan.

[39] Convict Department, Convict Lists, Memorials and Indexes.

[40] Convict Establishment Medical, Admissions & Discharges from Hospital (M32)

[41] Convict Department Registers, Character Book (R8)

[42] UK National Archives, Quarterly Returns of Prisoners, Prison Registers, Series HO8, Piece No. 134, Gloucester.

[43] Cheltenham Chronicle, 9 December 1856.

[44] UK National Archives, Institution & Organisations, Prison Registers, Series PCOM2, Piece No. 38.

[45] Convict Department, General Register (R1)

[46] Convict Department, General Register (R1)

[47] Convict Establishment Miscellaneous, Local Prisoners Registers (V16a – V16c)

[48] Convict Establishment, Receipts & Discharges (Rd5-Rd7)

[49] Convict Department Registers, Ticket of Leave Register (R6)

[50] Convict Establishment Miscellaneous, Local Prisoners Registers (V16a – V16c)

[51] WA Police Gazette, 9 August 1882, p.128, 129.

[52] WA Police Gazette, 30 August 1882, p.143.

[53] WA Police Gazette, 3 October 1883, p.161.

[54] WA Police Gazette, 1887, pp. 76, 116, 135.

[55] Southern Cross Herald, 16 March 1895.

[56] Central Districts Advertiser and Agriculture and Mining Journal (Northam), 16 March 1895.

[57] WA Record, 14 March 1895.