Residents of the South West of WA breathed a sigh of relief when the Forrest Highway was opened in 2009 – now there was a safe, uncongested and time-saving route to Perth. However there was a downside for the towns and businesses along the Old Coast Road and the South West Highway – fewer travellers meant less money spent.

The Old Coast Road via Mandurah was the first attempt to connect Australind and Bunbury with Fremantle and Perth. Prior to the surveying of its line in1842 by Marshall Walter Clifton and his surveyors, the few settlers of the area had to rely on irregular visits of sailing ships as their means of travel, the alternative being a trek on foot or on horseback through the bush to Fremantle.

Marshall Waller Clifton wanted to be seen as a man of action. As Chief Commissioner of the Western Australian Company it was his duty to create a thriving town and district at Australind. To expedite this, he needed a reliable road for transport of goods, people and mail to the capital, so he made the decision to mark out a road and clear it, using the resources of the Company. His plan included the provision of a ferry across the Mandurah Estuary.

On 28 October 1842 Clifton wrote – in his typically verbose style – to the Governor, explaining what had been achieved. His letter, accompanied by a favourable response from the Governor via the Colonial Secretary Peter Brown, was published in the Inquirer:

Australind, October 28, 1842.

Sir, — Adverting to your letter of the 23rd June last, conveying the sentiments of His Excellency the Governor on the subject of the new line of road which I had suggested between this town and Fremantle, I request you will do me the favour to inform His Excellency that the new line of road recently marked between Pinjarra and the Harvey having proved impassable during the late winter, and the old road crossing the upper estuary of the Harvey presenting almost insurmountable obstacles to travellers, while the whole line was more or less flooded to a great extent, I felt it my duty (more especially in consequence of communication by sea having been interrupted by the loss of the Devonshire,) to co-operate with the inhabitants of this place in opening a road along the line I had originally suggested via Mandurah. By means of a subscription a road from Mandurah to the head of Lake Clifton was marked and cleared twelve feet wide, while at the same time I caused by means of a party of men in the Company’s employ, the road to be marked and thoroughly cleared from thence to the Stony Plain.

Having accomplished this work with great rapidity, and having myself discovered a way of avoiding the Stony Plain and the swamps which skirt it, I caused the party before they returned to mark and clear a road by that route uniting it with the former high road about half way between the Stony Plain and Myarlup [Myalup]. I had previously cleared a capital road through the Company’s and Mr. Roe’s grant at the back of the tea tree swamp, instead of the old path by the estuary’s side, and thus, at this moment, a perfect road, thoroughly marked and cleared, exists from this place to Mandurah, by which persons may pass from one end to the other without wetting their feet or encountering any difficulty of any description. The advantages of this road have already been most manifestly known, almost daily communication takes place by it with Fremantle, while, as before observed, the other roads, if not altogether impassable, have been under water for 20 miles. The distance I consider to be 10 or 12 miles shorter by the newly marked road from Pinjarra to the Harvey, and 16 or 18 miles less than by the old Pinjarra road to Fremantle.

Simultaneously with this successful operation a subscription has been entered into for establishing a Ferry at Mandurah. A boat has been constructed, and I have great hopes that it will be ready to ply in three weeks or a month. I have no apprehension of any difficulty in the passage across Peel’s Inlet of this boat in almost all weather during the winter season, but the experience of this winter has shown that if it should be stopped for a single day at a time, like the Ferry between Fremantle and Perth, passengers can then cross in a whale boat, and almost always horses may be swam over at a point near Mr. Watson’s residence at Diddallam. I trust that the spirited exertions of the settlers at this place and of the body of subscribers to these undertakings as well as the assistance I have given by the Company’s means, will meet with His Excellency’s approbation and support. The journey from Fremantle from hence can be effected in two days and already great benefit has resulted from the facility of communication thus accomplished between this district and the metropolis of the colony alike beneficial to it and to the districts on the Swan.

I am, Sir, Your most ob’d’t humble serv’t.

M. W. CLIFTON,

Chief Commissioner of the W. A. Company.

0-0-0-0-0-0-0

Old homestead on Coast Road between Mandurah and Bunbury, ca. 1920.

Courtesy of State Library of Western Australia, BA1271/35.

Since being gazetted in 1842, the Coast Road has had a chequered past. Its fortunes as a route for carrying mail and travellers diminished with the collapse of the WA Company at Australind and the dispersal of many of its colonists. The few settlers who remained behind struggled to make a living on the nutrient-deprived soils of the coastal strip, while some took up better land along the foot-hills of the Darling Ranges, where a reasonable road was built by convict labour in the 1860s. This road via Pinjarra became the preferred option for travellers, leaving the Old Coast Road in an increasing state of disrepair, with a few abandoned buildings serving as ghostly reminders of failed expectations. It was not until the 1960s, with a rapidly expanding population in the South West, that plans were made for the revitalization of the Old Coast Road, which became a highway in 1969.[1]

Through hard work, those hardy citizens who stayed behind at Australind achieved success with some types of farming, though it was not until the 1950s that research by the Department of Agriculture led to supplements being added to the soils, creating benefits for the farmers along the coastal strip.

The following two newspaper articles, selected from a number published over the years, give us an idea of the Old Coast Road during different periods. The first one, written by a Bunbury Herald correspondent in 1908, paints a positive picture of the lives of some of those early settlers, who, despite the difficulties they faced, managed to make a living in the area.

The second article was written by local historian AC Staples in 1950, around the time when the possibility of re-vitalizing the Old Coast Road was being mooted. He gives us a more realistic account of the trials faced by the early settlers along this road, but finishes on a more positive note, with the prospect of this picturesque part of the WA coast being opened up for greater settlement and to tourists.

Travellers along the Old Coast Road at the 10 mile peg, now Cathedral Avenue.

Photo from Federation Display, courtesy Harvey Districts Historical Society.

ROUND ABOUT THE SOUTH WEST – THROUGH AUSTRALIND.

Bunbury Herald, 26 March 1908.

The journey to Australind is through Rathmines, the White-road suburb of Bunbury. Leaving its new and pretty Anglican church on the right, the road proceeds amid an avenue of handsome trees to the crossing of the Collie River, here a broad stream. The bridge which crosses it stands some four miles from Bunbury, and is a substantial structure. It affords several beautiful river views of the stream itself, and of the estuary beyond. At this point there are places naturally fitted for camping, and ideal picnic resorts. However, so far these natural beauties are not utilised by the erection of any structures of public entertainment. It may hopefully be surmised, however, that before many seasons this omission will be rectified.

Proceeding a few more pleasing miles with frequent shade trees, and a solid road which allows continuous views of the inland waters of the estuary, a cross-road sign intimates that a turn-off can be made to Brunswick. Close to this junction is the old homestead of the Clifton family, [Upton House] where Mr Joe Clifton resides, and carries on the occupation of a dairy farmer. The site is a very central one, and commands a fine sweep of land and water, good meadows and grain paddocks, with fine old trees at intervals, which give it a rather park-like aspect. A more homelike spot is hard to realise in the South-West. Numerous buildings, barns and outhouses, testify to the solidity of the situation. Here, too, is the Australind mail office. Another time details may be given of this owner’s operations.

Still further on this avenue extends, and passes a schoolhouse and several farms until the many farmsteads of the Rogers family [Cook’s Park] one after another loom in sight. These lands lie well to the right of this road and generally face the Estuary. The original homestead of this family was the one visited, and details were obtained. This property belongs to Messrs Rogers Bros, and is a very fine and well developed holding of some 5000 to 10,000 acres of all accounts. It may here be remarked that some farmers object to give the true size of their estates while others seek to magnify them. Thus the above wide-margin estimate becomes a fair indication of magnitude. Here the fine black and level lands stretch their fertile length through many well-worked paddocks. Potatoes proved to be the leading crops, although many classes of market produce are nourished here, and Mr Rogers assured me that some 100 tons of these tubers were raised annually. These potatoes were of a sound and satisfactory quality and found ready markets. Messrs Rogers are also cattle breeders and have extensive herds, their oat-hay crops are large and well up to expectations. Such a property as they possess becomes of increasing value the further it is worked, and proves the fortune of those who know good land enough to keep on it. A brotherhood such as theirs becomes a very strong stake in this colony.

A few miles further, and at the head of the Estuary, the estate of Messrs J. E. M. Clifton and Son is reached. Here the waters of this small inland sea abruptly terminate in a full-bosomed but shallow bay. These waters were once well stocked with fish, but now, owing to man’s contrivance within the Collie River, their race has been scared, netted, or scattered, and these haunts know them no more. So much for man, the unheeding destroyer.

The name of Rosamel marks the property of Mr J. E. M. Clifton, a fine free-hold estate of 3,500 acres. It might command an easy approach, both by land and water, if channels were maintained, and the high-road better regarded. At Wokalup also Messrs Clifton and Son farm another 2,000 acres, these being mainly for grazing purposes. At Rosamel however, these gentlemen conduct both mixed and dairy farming, these being together undertaken on scientific lines. Grazing is also well regarded, in view of the future development of this property. Pork, too, is grown by them, and swine here offer good returns. In regard to his dairy herd, Mr Clifton has found that some strains of Jersey do very well, but that with him they cannot be compared to Shorthorns. He has managed to milk his dairy cows all the year round, and this for the last 16 years. Natural pasturage, picked up from the paddocks round, has been all that these herds have had, and feeding has not been followed, nor has it yet been required. His cows average during the milking season about 71b. of butter apiece, and this output is maintained yearly. Several of his paddocks are cultivated, while others are retained under pasture for night paddocks for his cattle. Such meadows, used in rotation year by year afford a full and sufficient supply of pasturage always accessible and rich. In effect, Mr Clifton considers that his lands on the estuary are remarkably good for stock.

In cultivated paddocks of couch grass, some 250 acres in extent, this farmer manages to stock about fifty head of cattle, and 450 sheep. In grain growing. Mr Clifton has returns of fifty-five bushels to the acre, and this, as usual, without adding any manure to the land. His oat-hay crops maintain the 2 ton per acre average, and may always be accounted reliable. Altogether Mr Clifton considers the choice of Captain Roe, the founder of this farmstead, more than justified, and is confident of its future value. These lands of Rosamel are of a black, to blue, clay in some parts, in others running into red, or grey, loam, and sandy soils. Grapes have been tried on the latter class of lands, but have experienced too many ravages of storm, and have felt too much the rapacity of crows, to be a very successful crop. They were however, very good whenever spared. In result, the voracity of the local crows caused fruit growing to be abandoned as an industry at Rosamel. Mr Clifton is, comparatively speaking, only making a start at sheep farming. He has some five hundred head, of sheep, and now is keeping all the lambs for the flock. It is, as we have seen, as a dairy farmer that Mr Clifton follows his profession. In this province he has gained local fame, and is considered to produce about the best butter in the district. The lands of Mr Clifton, judging from the gigantic trees here and there to be seen on them, must have been won from a massive forest of timber, and the heaviest of scrub thickets. Indeed this gentleman said that the clearing was truly ‘awful,’ or words to that effect.

A mile above Rosamel, and 13 miles from Bunbury, the estate of Parkfield, which belongs to Mr G. C. Rose, is situated. This fine property descended to Mr Rose from his father, and consists of about 12,000 acres, extending from the sea coast to the foot of the Darling Ranges. Grazing and general farming here are chiefly followed with very satisfactory success. The lands here have been very densely timbered thus the cost of cutting out the smaller trees and leaving half cleared spaces, has come to £4 an acre. Mr G. Rose was absent at the time of calling, and my informant was Mr Hamilton, who superintends the property. He stated that there were here 770 acres under crop, and that oat-hay proved the most successful of all the paddock produce; it was hardier than other grain and could stand the gales from the estuary.

Limestone land which here forms the subsoil proves remarkably good for growth of all kinds. Vines here cultivated by Mr Rose are exceedingly well developed, with very large and luscious clusters. Muscatels among white, and the Red Prince and Gros Wilhelm, among red and blue grapes, give surprising results; Mr Hamilton assuring me that the Red Prince went 7lbs to the bunch, and the Gros Wilhelm as much as 10lbs, and even over. It is chiefly, however, as a grazier that Mr Rose excels. He here has numerous flocks, and raises his ram lambs, afterwards exporting them to Kimberley, for other holdings he possesses there. Merinos in the district, ‘ do not do well,’ said Mr Hamilton, but Shropshires give far better results. Mr Rose has some 2,500 sheep on this estate, and all are in very satisfactory trim indeed. Their classes are high and notable, and each year he has succeeded in gaining wool prizes. He has also gained the 1st prize, silver medals for rams and ewes, and the 1st prize for general farm entries and products; also prizes both for cattle and horses.

It will be, therefore, clear that Mr G. Rose has successfully followed the masterly ‘lead’ his father gave him, and has prospered on the land. The appearance of the lands around Parkfield is singularly pleasing. Well cleared meadows face the estuary, wide paddocks lie beside them under cultivation, then amid open park lands the homestead stands, with a well-planted garden before it of pine and cypress trees. All seems most finished and homelike; such is Parkfield at the far end of the estuary.

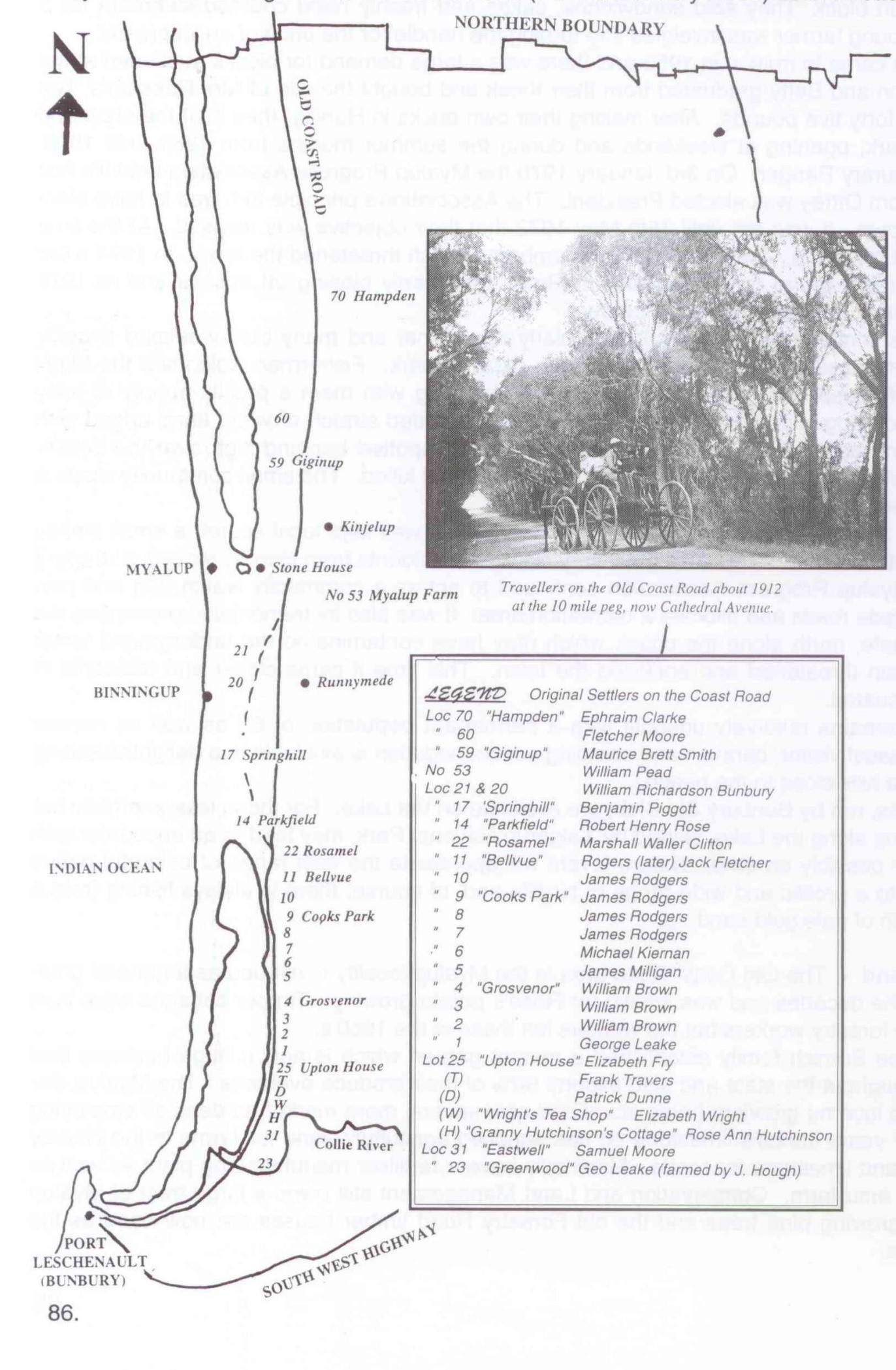

Map showing location of properties along the Old Coast Road.[2]

Map showing location of properties along the Old Coast Road.[2]

From ‘Shire of Harvey, Proud to be 100, Centennial Book’, p. 86.

0-0-0-0-0-0-0

Cathedral Avenue, previously Old Coast Road c1940.

Photo from Federation Display, courtesy Harvey Districts Historical Society.

COAST ROAD BECOMES A GHOST ROAD, by AC Staples.

West Australian, 13 May 1950

Someone returning from a camping holiday said that he crossed the Old Coast Road unexpectedly as he pushed his way through the scrub. It wandered off north and south into the bush, with a fallen-in well close on the left-hand side. On he travelled along it a little way and came upon the white skeleton of a limestone homestead under an ancient fig-tree. The Old Coast Road runs south from Fremantle, but farther east than the Mandurah road, then crosses the bar and continues on along the western shores of the Harvey Estuary and east of Lakes Clifton and Preston to Australind.

From time to time someone asks that the Mandurah-Australind section should be reopened. At a conference at Harvey the other day the plea for rebuilding was supported by the arguments that it would open up more land for settlement and, as well as relieving the congestion on the present Perth-Bunbury road, would provide another tourist route.

Let us travel the route of this proposed new-old road, turning right at Mandurah instead of left. A few miles south you catch a glimpse of a vast sheet of water stretching away on your left as far as the eye can see. This is the Harvey Estuary, one of our great hidden fishing resorts. We skirt its western shores for about 12 miles, selecting the site of our next fishing camp. Now we turn right, across a sandy ridge, and soon find ourselves on the eastern shores of Lake Clifton.

Map showing the Old Coast Road and South Western Highway

between Mandurah and Bunbury.

Travelling quickly south, we catch repeated views of Lakes Clifton and Preston, nearly as rich in minerals as the Dead Sea itself. Here are the historic homestead sites of the old settle- ment at the Peppermint Grove, Hampden, Myalup, two-storeyed Spring Hill, rambling Parkfield and Rosamel at the head of Leschenault Inlet. (You could have turned right at Myalup to look over the sea-side camping area developed by the Harvey Road Board.) Soon the upstairs windows of Upton House come into view on the left, with the Australind Memorial on the right near the original landing place. Here is another campers’ paradise with the excellent fishing of the Collie River a few miles nearer Bunbury. But these sights and holiday resorts are hidden from most of us because the Old Coast Road is impassable.

The Coast Road was declared as a consequence of the creation of the Australind settlement on Leschenault Inlet in 1840-41. It is not subject to flooding because it runs along the lime-stone ridge which separates the lakes from the swamps lying to the east towards the hills. Supplies to Bunbury came by sea from England or Fremantle to be carried up the Leschenault Inlet by boat to Australind. Early settlers therefore tended to settle close to the sea.

With the initial failure of the Australind Company, some of its members moved north along the Coast Road to the limestone country at the head of the Inlet. John Allnutt and Ben Piggott leased blocks bought earlier by land speculators and William Crampton settled on company land at the northern end of Myalup Swamp, just east of the road. One of the earliest settlers on the road farther north was Maurice Brett Smith, who purchased land as early as 1844.

He was closely followed by Ephraim Clarke, John Fouracre and John Sutton closer to Mandurah. Smith, Fouracre and Sutton were not of the Australind Company but went south from Fremantle in search of land. This was the first settlement north of Bunbury and remained a fairly prosperous community until about 1900.

Looking at this country today with its forlorn ruins of farm houses and its little patches of clearing on land we know to be deficient in all sorts of necessary soil constituents, it is difficult to understand how the old settlers survived so long. They were fortunately men of initiative who knew how to make the best of their surroundings. Dairy cattle could be kept in good condition by periodically changing them from the coast to the ‘station’ on the clay country near the hills. This practice counteracted the effects of soil deficiencies which were so bad that cattle would not grow to maturity on the coast.

Potatoes on swamp edges. However, excellent crops of potatoes would grow on the edges of the peaty swamps between the limestone ridges. Wine from the Parkfield vineyards found a ready market around Bunbury. Settlers even managed to grow enough wheat for their own use. This was of course, sent to be ground at Forrest’s mill at Picton. Quite a lucrative cattle trade grew up, the beasts passing through the hands of such well-known cattle men as the Roses, McLartys, Ramsays, Blythes and Wellards.

Then this thriving settlement collapsed. This calamity was caused by the fencing of the selections taken up by new settlers along the new road built under the foothills to the east. The cattle could no longer roam at will.

Some of the coast farmers moved to new homesteads on the clay country. They taught the new settlers their method of dealing with the soil deficiency by sending their cattle periodically to the coast, which thus retained a certain amount of importance as the out-station country. After the opening of the railway to Bunbury in 1893, no new settlers selected along the Coast Road because it was too far from this new method of transport.

The introduction of superphosphate after World War I finally killed the coast settlement. The application of superphosphate produced such good pastures on the clay country that it was no longer necessary to keep coast land as a change for the cattle. Nobody wanted the coast.

Even the sowing of superphosphate would not remedy the deficiencies of its soil. The Coast Road became the Ghost Road wandering through a ghost settlement.

West Australian scientists have lately discovered that the application of copper and potash with superphosphate will do for the limestone country what superphosphate alone did for the clay land. The new strains of clover will provide a pasture for a new settlement. Experiments are already being carried out by progressive farmers with the aid of the Department of Agriculture. The first step will be to establish new pastures for cattle and sheep grown for their meat. Dairying might follow later. The resettlement of the coast district may take many years, but new knowledge suggests bright possibilities. In the meantime, the rebuilding of the Old Coast Road would prove a boon to holiday-makers and tourists as well as to the pioneers of the new settlement.

0-0-0-0-0-0-0

Some sections of the Old Coast Road were incorporated into the Forrest Highway. An excellent article on the Forrest Highway can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forrest_Highway

[1] Marion Lofthouse, Kerry Davis, Shire of Harvey, Proud To Be 100, Centennial Book, Noble Publishing, Shire of Harvey, 1995, p. 87.

[2] The insert shows names of purchasers; note that Elizabeth Fry didn’t come to Australia and others, like George Leake and George Fletcher Moore, purchased land but did not settle in the area.