By Irma Walter 2017

Photo showing Leschenault Estuary and Peninsula.

Courtesy of Leschenault Catchment Council Inc.

Introduction

The Leschenault Peninsula is a narrow low-lying strip of land 11 kms long, situated north of Bunbury on the Leschenault Estuary. The area was of significance to local Noongar people long before white settlement, when the land was taken up by Charles Robert Prinsep of Calcutta, for the purpose of breeding horses for the Indian trade, followed by a succession of owners for grazing stock in the winter when their inland properties were boggy. During that time it was used by well-known Fenian convict John Boyle O’Reilly as cover while waiting to escape on the Gazelle.

In modern times it was inhabited by alternative lifestylers, then used by a factory as a dumping ground for its effluent. Known as the Leschenault Peninsula Conservation Park since 1992, the area is popular as a recreational reserve, where visitors can learn about its chequered history while enjoying the natural surroundings and wildlife.

Early Settlement

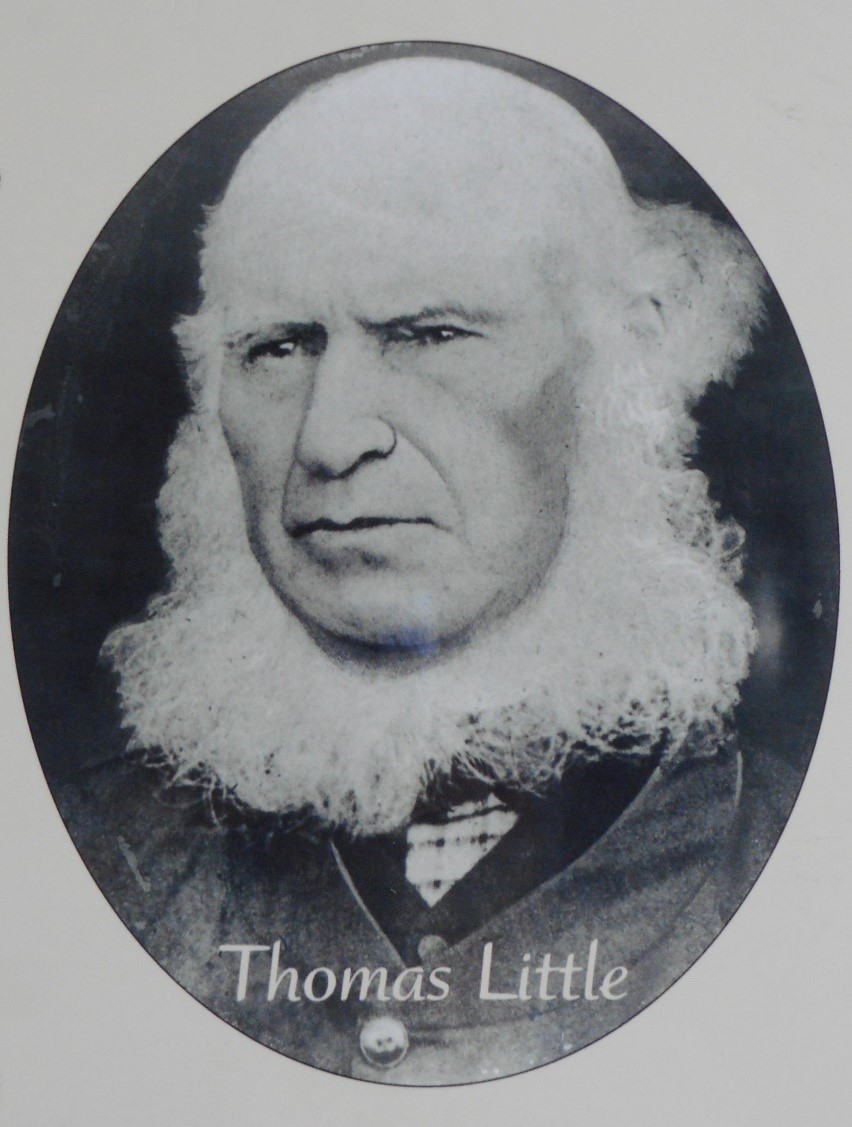

In February 1838 Thomas Little arrived at Fremantle on the Gaillardon, the first ship to be contracted by the Bengal Australian Association, a group formed in India with the aim of increasing interaction, both personal and commercial, between India and Australia. Thomas Little, an Irishman formerly in the employ of the East India Company, was sent from Calcutta to establish an estate in WA for Charles Robert Prinsep, Advocate-General of Bengal, for the purpose of rearing horses for the British Army in India.[1] Both Thomas Little and Charles Prinsep were listed as foundation members of the Bengal Association.[2]

After landing at Fremantle, Little proceeded to Bunbury, where he found temporary accommodation at a property named Moorlands. He had some difficulty finding suitable land, eventually purchasing on behalf of Prinsep Location 24, consisting of 1,832 acres on the Leschenault Peninsula, at a price of 5/- per acre.[3]

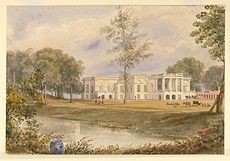

The Leschenault property faced the Indian Ocean and was comprised mostly of sand dunes, apart from some fertile flats along the estuary.[4] Little built a house on the northern end of the peninsula and named it ‘Belvidere’ in honour of the Prinsep family mansion in Calcutta.[5]

Illustration of Belvedere House, Calcutta, in 1838, by the Anglo-Indian merchant and artist William Prinsep. The estate belonged to the Prinsep family, who sold it to the East India Company in 1854.[6]

Illustration of Belvedere House, Calcutta, in 1838, by the Anglo-Indian merchant and artist William Prinsep. The estate belonged to the Prinsep family, who sold it to the East India Company in 1854.[6]

Agricultural Use

Prinsep had originally acquired property near Launceston in Tasmania (then known as Van Dieman’s Land) for the purpose of breeding horses for the British army in India, but decided to transfer his stock to the Bunbury area in WA, due to its closer proximity to the Indian market.

His overseer Thomas Little set out to develop the ‘Belvidere’ estate as a horse and cattle venture. He established two cattle herds, one of which was Bengali cattle or water-buffalo, which were kept at the Bengal Station at the northern end of the property and were used for ploughing and as beasts of burden. These animals were herded by Thomas Jackson.[7] (It was Jackson who later sheltered escaped convict John Boyle O’Reilly.) Over the years the buffalo at ‘Belvidere’ crossed with local cattle breeds and remained a feature of the area.[8]

Prinsep was convinced that Asian immigration was the answer to Australia’s labour problems. Angela Woollacott states in her book that a contingent of 37 Indian lascars, one Chinaman and 13 British workers accompanied Thomas Little’s family to WA.[9] At ‘Belvidere’ they were employed in erecting buildings and fences, clearing land, establishing gardens and caring for stock. Some of the Indian employees absconded, while others returned to India at the end of their term of indentured service. In 1852 it was reported that one of the ‘coolies’ had disappeared. Following a lengthy but unsuccessful search of the property, it was reported that another Indian servant named Nannaram was arrested some months later, suspected of involvement in the man’s disappearance:

A coolie of the name of Nannaram, was apprehended and sent to gaol on suspicion of his having murdered another coolie at Belvedere, about 8 or 10 months since. He was found secreted amongst some firewood in a small room occupied by his wife; close beside him was a large box, with a bed in it, where he had been at times secreted; a sword was also found, recently sharpened, and a heavy bludgeon thickly studded with shoe-nails. He will be detained in custody until particulars arrive from Australind respecting the missing man. His wife had taken her passage by the Eugene, and no doubt intended to convey her husband on board in the large box.[10]

In 1842 Thomas Little took his family back to Calcutta on a holiday and trading mission. They returned to WA the following year on the Hoogley, with 28 Arab mares and two stallions, as well as various goods for sale. They were accompanied by three invalid British Army officers who were seeking respite from the oppressive Indian heat.[11] Part of Prinsep’s long-standing vision for ‘Belvidere’ was that it would be used as a place of recuperation for British soldiers in our more salubrious climate.[12] While away, Denzil Onslow acted as manager at ‘Belvidere’.[13]

Other Australian colonies expressed interest in breeding horses for the trade, but WA was best placed geographically to access the Indian market. Although the trade lasted for a number of years, the success of the venture was mixed. Conditions on board ships were not ideal for the purpose, especially in rough conditions, and infections spread quickly in such close quarters. In 1850 it was reported that 16 out of the 20 breeding mares intended for Mr Prinsep’s establishment at ‘Belvidere’ had perished during a voyage on the Mahomet Shah from Van Diemen’s Land, and of the four surviving horses, one appeared to be ‘more dead than alive.’[14] In another incident, Mr N Shaw died after being kicked by a horse consigned to Thomas Little, during a voyage from India on board the Templar.[15]

Although it was made clear that the British Army was only interested in well-bred stock, there were reports that many of the animals selected did not reach the required standard. A report on the state of the WA livestock market in 1867 revealed that of 92 horses shipped from Bunbury to Calcutta that year, the highest price reached was £75, and several others sold for £50 to £60, but the remainder did not fetch prices sufficient to cover expenses. At the same time breeders were informed that another shipment would be sent as soon as a suitable ship could be procured.[16]

In 1850 it was announced that Prinsep’s WA land holdings were greatly increased with the purchase of James Henty’s grant of 20,000 acres on the south side of the Collie River, at the price of 2s.6d. per acre.[17] By 1852 Thomas Little acquired a property of his own in the area then known as ‘The Pools’ at Dardanup. He purchased the land from the Rev. John Wollaston, who had moved to Albany. This property was later called ‘Dardanup Park’.

After being replaced as overseer at ‘Belvidere’ in 1854, Little set about developing his Dardanup property, establishing an orchard and vineyard there. A staunch Catholic, he donated 50 acres of land and provided materials for the building of a substantial church there. Over the years, Little sponsored Irish Catholic settlement in Dardanup. Thomas Little passed away on 5 November 1877, and his funeral was said to be the largest ever held in the area, such was the high esteem in which he was held.[18]

From Department of Parks and Wildlife information boards on the peninsula.

He was replaced at ‘Belvidere’ by a new agent, Wallace Bickley, who held agencies for various insurance companies in the colony, and is said to have made frequent journeys to India as a horse trader in the 1850s.[19] Bickley appointed his son-in-law William Owen Mitchell as overseer of the ‘Belvidere’ Estate. Mitchell held the position until 1860.[20]

From 1861 to 1869 William Bedford Mitchell (not related to William Owen Mitchell) was employed as manager. The estate duties over this period included a continuation of the horse trade and the export of jarrah railway sleepers to India.[21] (WB Mitchell’s obituary in 1907 described him as a well-known horse-breeder and racer, stating that he carried on a most extensive business in shipping horses to India.[22]) Another newspaper article on the history of the pastoral industry in WA claimed that ‘Belvidere’s horse trade with India ceased around 1880.[23]

According to Thomas Hayward, there was a large dairy set up at ‘Belvidere’ during this period. The problem of retaining workers prepared to milk by hand was evident:

About 1860 a dairy with a fair number of good cows was established at Belvidere, on the Prinsep Estate. This was continued several years, and a considerable quantity of butter produced and sent to Perth and Fremantle. Eventually, through difficulty in finding milkers, and the business being unremunerative, it was given up, and soon after a bush fire made a clean sweep of the whole homestead.[24]

Charles Robert Prinsep died in 1864 in England as a result of a stroke suffered earlier in India. His son Henry Charles Prinsep was born in India in 1844, but had been sent to England at the age of nine, following the death of his mother. There he was educated, living with his uncle Henry Thoby and Aunt Sara Prinsep. Of artistic temperament, he showed promise when attending art lessons along with his cousin.

Henry Charles Prinsep came out to WA to inspect his late father’s property in 1866. Soon after meeting Josephine Bussell of the Vasse, they were married in 1868 and Henry decided to stay in WA, taking control of the ‘Belvidere’ estate from around 1869, under the guidance of WB Mitchell as his studmaster. [25]

As a supplement to the horse trade, Henry took advantage of the boom in railway construction in India, commissioning vessels to carry jarrah sleepers there. However, following the loss of the Hiemdahl in 1870 at the mouth of the Hoogly River in India, he found that his cargo of horses and timber was uninsured. Back in Western Australia Prinsep struggled financially for another three years, but falling prices defeated him and the estate was sold in 1874 by his creditors to Henry Whittall Venn.[26]

In Perth, Henry Prinsep moved in artistic and literary circles. Following the failure of his shipping enterprise, he was employed for a time as drawing master at the Perth High School, under Headmaster R. Davies.[27] He later joined the WA Civil Service where he served as Chief Clerk in the Lands Department before becoming under-secretary in the new Department of Mines. At the time of his retirement Henry held the role of Chief Protector of Aborigines.[28]

At the time when Venn acquired the Prinsep property, he also purchased the properties of Thomas Little. The Venns chose to reside at Little’s former residence at ‘Dardanup Park’, using ‘Belvidere’ for grazing purposes, rotating the stock between Dardanup and the coast. The ‘Belvidere’ homestead was used as a seasonal base for stock work and as a summer holiday retreat by the family. After HW Venn’s death, ‘Belvidere’, along with his Dardanup properties, were passed on to his nephew, Frank Evans Venn, who managed ‘Belvidere’ in much the same way, with seasonal grazing and as a summer retreat. [29]

In 1898 the ‘Belvidere’ property was being leased to James Milligan, Jnr.[30] He was still there in 1903.[31] The original ‘Belvidere’ homestead is believed to have burnt down prior to 1900. The homestead subsequently built for the Venns was also destroyed by fire. The exact year is unclear but is thought to be around 1936. The jetty built by Frank Venn was destroyed by the same fire. Remains of the jetty are still present.[32]

In November 1920 the Venns sold the ‘Belvidere’ Estate to Lewis McDaniel, a farmer from Dardanup. McDaniel used ‘Belvidere’ as an extension of his Dardanup properties, and, like his neighbours on the peninsula, he seasonally grazed stock. In 1924 it was reported that the separate kitchen building at ‘Belvidere’, a thatched roofed structure, was burnt to the ground, despite the efforts of Mrs McDaniel (Jnr) and her family. Luckily a southerly breeze prevented the fire from spreading to the main house.[33]

Ownership of ‘Belvidere’ was transferred in 1954 to D.M. McDaniel.[34]

The ‘Commune’ Era

In March 1967 ‘Belvidere’ changed hands again when the property was bought by Albert Thomas Bastow, but in November of the same year, was passed on to Wallace (Wally) Greenham and Shirley Rodda. They were the last private owners of ‘Belvidere’. For a large part of their ownership, ‘Belvidere’ was used as a site to foster alternative lifestyles. A small commune developed and by the late 1970s its membership had grown sufficiently to warrant the employment of its own teacher. At its peak, occupancy of the commune comprised 14 houses.[35]

Commune Era housing[36]

After nearly twenty years’ occupation by a succession of alternative life-stylers, the Harvey Shire Council made the controversial decision in July 1984 to serve the landowners with a notice to demolish the commune shacks -which did not comply with building regulations – within 56 days.[37] By March 1985, after months of protests, the shacks were finally demolished by the landowners, who lived at Denmark.[38] Some supporters compared the low environmental impact of the occupiers with the pollution resulting from effluent being dumped on the southern tip of the peninsula by the Laporte titanium dioxide plant at Australind.[39]

Pollution on the Peninsula

Thomas William (Bill) Harris had owned the southern section of the Leschenault Peninsula since 1886. Throughout the period of his ownership and later, when the property was passed onto his sons in 1929, it was used for stock grazing. Like the ‘Belvidere’ owners, the Harrises also grazed the coastal properties as alternative pasture to the wetter lands of Waterloo and Dardanup.[40]

Dredging claims for the extraction of mineral sands at Koombana Bay were registered in 1947.[41] Shortly after WW2, Bunbury was one of the Australian locations being considered by the British company La Porte Industries for the establishment of a titanium extraction plant. However it was not until 1960 that an agreement was signed by the Chairman of Laporte Industries Ltd and Premier David Brand for construction of a factory at Australind.[42] Under the agreement, the WA State Government accepted responsibility for the disposal of all effluent from the works up until 2011.[43] Sixty hectares of land situated behind the golf course at Clifton Park was purchased by the company, and construction of the pigment factory commenced in 1961.[44] The plant produced titanium dioxide, a material used in products such as printing inks, paper, cosmetics and ceramics.

In 1965 the Harris property was bought to facilitate the disposal of acid effluent from Laporte’s titanium dioxide plant, which later became Millennium Inorganic Chemicals Limited’s Finishing Plant at Australind.[45]

With increasing demands for suitable effluent disposal sites, the Western Australian Government indicated its wish to buy ‘Belvidere’. The commune occupants were subsequently moved from the area and in 1984 the Government negotiated to purchase the land to facilitate effluent disposal.

From 1964 to 1990 acid was deposited on the Leschenault Peninsula as a bi-product from the Laporte titanium sulphate processing plant at Australind

Each year the plant produced approximately 36,000 tonnes of titanium dioxide pigment and 2,400 million litres of acidic waste effluent. Initially the acid was deposited directly into the ocean beach, resulting in large iron stains in the water and on the sand. This led to public outcry and the practice ceased in 1968. After this, the effluent was deposited into cleared depressions in the dunes, where it percolated through the alkaline sand, neutralising most of the acid. In 1989 a chloride process pigment plant in Kemerton replaced the existing plant and the acid disposal ceased the next year.[46]

Rehabilitating the Area

After decades of effluent disposal, land managers were then faced with the enormous task of rehabilitating 18 acid ponds and eroded dunes covering nearly 100 ha, around 10% of the Peninsula. Between 1986 and 1992 four government departments and contractors worked intensively to rehabilitate the degenerated landscape. Acid ponds were filled in, dunes rebuilt and tree loppings or ‘brush’ was laid to minimise erosion. Thousands of seedlings were planted and seeds sown to stabilise the area. In 1992 the new recreational area was declared an A Class Conservation Park, to be known as the Leschenault Peninsula Conservation Park.[47]

John Boyle O’Reilly, Convict.

Leschenault Peninsula Conservation Park is now open to the public, with Buffalo and ‘Belvidere’ beaches easily accessed by car. Facilities for visitors include walk circuits, picnic and camping areas, with information boards telling its history.

One of these panels tells us the story of a colourful character who had a brief association with the area. His name was John Boyle O’Reilly, born in Ireland in1844. He was one of the 62 Irish political prisoners among the 279 convicts who arrived at Fremantle on 9 January 1868, onboard the Hougoumont. O’Reilly was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, known as the Fenian Movement, a secret society of rebels dedicated to an armed uprising against British rule. As a member of the 10th Hussars in Dublin, O’Reilly turned his energies to recruiting more Fenians within his regiment, bringing in up to 80 new members. When caught, he was tried and sentenced to death on 9 July 1866 for treason.[48]

In the same year as his arrival in Fremantle, O’Reilly was transferred to the Bunbury Convict Depot to work as a member of a road crew. They were strictly disciplined but not closely guarded, as it was believed that there was nowhere for prisoners to go.

As part of a well-prepared escape plan, and assisted by local Catholics, O’Reilly made his way to the Leschenault Peninsula, from which he planned to row out to sea and board the American whaling ship Vigilant, but the Captain of the US ship reneged on the deal. While waiting for another escape vessel, O’Reilly sheltered, with the assistance of the Jackson family, in the dense peppermint woodlands in the vicinity of Buffalo Homestead (Buffalo Hut). He finally made his escape aboard the American whaler Gazelle on 3 March 1869, eventually settling in Boston, USA, where he established himself as a humanitarian, newspaper editor, writer, poet and orator. He arranged for the purchase and fitting out of the Catalpa which, on 17 April 1876, was involved in the rescue of six of the remaining 10 Fenians held in Fremantle Prison.[49]

O’Reilly died in Boston on 10 August 1890. A monument erected to the memory of John Boyle O’Reilly stands at the northern entry to Leschenault Peninsula, within 200 metres of the site of the Jackson family’s hut. In recent times his exploits have been celebrated annually at the site by the John Boyle O’Reilly Association of Bunbury, WA.

Buffalo Hut, the home of the Jackson family. Courtesy of Bunbury Historical Society.

………………………………………………………………….

Further Resources:

‘Back to Belvidere’ an oral history, is available through Harvey History Online.

PT O’Shaughnessy, Laporte, a history of the Australind titanium dioxide project, 2011.

Malcolm Allbrook, Henry Prinsep’s Empire: Framing a distant colony, ANU Press, 2014.

Lost Belvidere at https://www.facebook.com/LostBelvidereWA/

[1] West Australian, 7 December 1946.

[2] Hobart Town Courier, 10 November 1837.

[3] AC Staples, They Made Their Destiny – History of Settlement of the Shire of Harvey 1829-1929, Shire of Harvey, 1979, pp.55-57

[4] Ibid.

[5]Note: Prinsep chose to use a variation of the spelling of the name Belvedere, to highlight the difference between the two properties.

[6] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belvedere_Estate

[7] Heritage Council of WA, inherit, state heritage.wa.gov.au

[8] West Australian, 7 December 1946.

[9] Angela Woollacott, Settler Society in the Australian Colonies – Self-Government and Imperial Culture, Oxford University Press, 2015, p.57.

[10] Inquirer 8 September 1852.

[11] Inquirer, 1 March 1843.

[12] Perth Gazette, 4 March 1843.

[13] Bunbury Herald, 1 February 1919.

[14] Inquirer, 5 March 1850

[15] Perth Gazette, 30 April 1862.

[16] Inquirer, 11 December 1867.

[17]Perth Gazette, 31 May 1850.

[18] Inquirer, 21 November 1877.

[19] Brian Rose, unpublished.

[20] Ibid.

[21] William Bedford Mitchell was the father of Sir James Mitchell, later Premier of WA.

[22] Western Mail, 6 April 1907.

[23] Western Mail, 21 December 1917.

[24] Bunbury Herald, 30 August 1913.

[25] Morgan Smith, unpublished paper on Henry Charles Prinsep, c1990s.

[26] AC Staples, Prinsep, Henry Charles (Harry), (1844-1922), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Melbourne University Press, 1988.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Department of Conservation and Land Management, Leschenault Peninsula Management Plan 1998 – 2008.

[30] Bunbury Herald, 27 January 1898.

[31] Bunbury Herald, 20 July 1903.

[32] Fletcher, unpublished, in Department of Conservation and Land Management, Leschenault Peninsula Management Plan 1998 – 2008.

[33] South Western Times, 15 April 1924.

[34] Department of Conservation and Land Management, Leschenault Peninsula Management Plan 1998 – 2008.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Department of Parks and Wildlife information boards on the peninsula.

[37] South Western Times, 12 July 1984.

[38] South Western Times, 14 March 1985.

[39] South Western Times, 24 July 1984.

[40] Fletcher, in Department of Conservation and Land Management, Leschenault Peninsula Management Plan 1998 – 2008.

[41] Daily News, 12 March 1947.

[42] PT O’Shaughnessy, Laporte – A History of the Australind Titanium Dioxide Project, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, WA, 2011, p.31.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid, pp.31-32.

[45] In 2017 the business is owned by Crystal Global.

[46] Department of Parks and Wildlife information boards on the peninsula.

[47] Department of Parks and Wildlife information boards on the peninsula.

[48] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Boyle_O’Reilly.

[49] Wendy Birman, Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/oreilly-john-boyle-4338.