By Irma Walter, 2020.

One of the more notorious convicts sent to Western Australia was John Goodenough, who first arrived here onboard the Clara in 1857 under the alias ‘John Williams’. Following his escape from the colony in 1862 on a whaling ship, he eventually found his way back to England, where he took up lodgings under the alias ‘Captain John Smith’ and carried out a series of daring robberies before being re-arrested in 1864. He was sent back to Western Australia onboard the Belgravia in 1866, under the name ‘John Smith’. Determined to escape once again in 1867 he was involved in a daring escape perpetrated by a group of prisoners from Fremantle Prison, before coming to an untimely end while attempting to avoid capture near Pinjarra.

Early Years

John Goodenough’s life began at Thorpe in Surrey in 1829. He was the son of a peddler also named John Goodenough and his wife Harriet, née Dry. His siblings were William, Harriet, Robert, Hannah and George.[1]

John’s life of crime began early. A John Goodenough, aged 16, was whipped and sentenced to two months’ gaol in 1841, for larceny from the person in Buckinghamshire.[2]

The 1851 census lists John Goodenough, aged 28, roadman, in Reading Gaol, along with his co-offender Hector Fenner, a gypsy, serving a term of one month for larceny.[3] [Reading Gaol had been re-built in the 1840s, designed to operate under the Separate System, whereby inmates were totally isolated from contact with others, apart from instruction in Bible reading, which was intended as a reformatory measure. The total lack of physical activity and outside contact resulted in increasing mental breakdowns among inmates. By 1855 hard labour was re-introduced.[4]]

Reading Gaol, 1844.[5]

Reading Gaol, 1844.[5]

His experience in gaol did not deter Goodenough from further crimes. In October 1851 he was tried at the Central Criminal Court for stealing a tobacco box and three sovereigns and was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment.[6] On 10 July 1854 he received a sentence of eight months for larceny at Abingdon in Berkshire.[7]

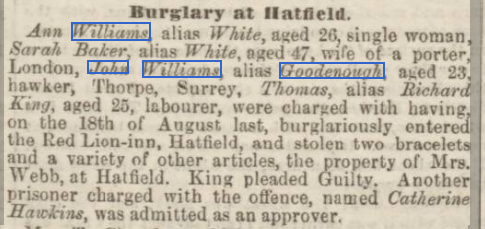

In those days previous convictions were taken into account during sentencing and as a consequence the use of aliases was a common practice among serial offenders. In 1855, together with his old associate-in-crime, Hector Fenner, Goodenough was arrested under the name ‘John Williams’ and was charged with burglary at Everleigh. By that time however he was well-known and his real name was recorded beside his adopted one. During the trial the two offenders put the blame for the crime on each other. Fenner, a ticket-of-leave man, was considered the prime offender and was sentenced in July that year to transportation for 20 years. For some reason John Williams/Goodenough was acquitted.[8] However he was back in Court a few months later on 3 December 1855 with several others, including two women, one said to be his wife Ann Williams (alias White), all charged with burglary at Hatfield:

Described by this stage as ‘perfectly incorrigible’,[9] he was convicted as ‘John Williams, alias Goodenough’ of burglary and due to former convictions of felony, was sentenced to 15 years’ transportation.[10] The others received sentences of six years. At the conclusion of the trial Williams/Goodenough thanked his lordship, but claimed that he was ‘a very ill-used, honest and persecuted man’, whose wife Ann Williams (alias White) had taken up with another man who was the real perpetrator of the crime.[11] [Whether the pair had ever married is not known. Ann was described as a single woman during the trial.[12]]

Goodenough’s desperation at being locked up was all too apparent when an attempt to escape from Hertford Gaol in January 1856 while awaiting transportation was foiled by a warder:

A PRISON BREAKER – John Williams, alias Goodenough, who was convicted at the recent winter assize of burglary at Hatfield, and sentenced to fifteen years’ transportation, has made a desperate attempt to escape from the gaol at Hertford. The warder, while on his rounds at night, heard a noise in one of the cells, and looking through the small inspecting glass in the door, observed him busily engaged at the window of his cell. He had already removed the sash, and was endeavouring to loosen the iron bars. Assistance having been procured, the cell door was opened, and the convict confronted. He stood like a bull at bay, desperate and dangerous. Having been ironed he became almost frantic, and threatened to destroy himself, and the means of self-destruction having been carefully put out of his reach, he resolutely refused food, having determined on starving himself. For sixty hours he persisted in this resolution, when an order came for his removal to Millbank. He then for the first time faltered, and accepted the food offered him. He was removed in irons. Goodenough once attempted to escape from Reading gaol, and on being discovered was ironed, as is usual in such cases. Subsequently appearing to be docile and well behaved, an offer was made to him to remove his fetters; but he declined it. This excited suspicion, and on his irons being examined, it was found he had chafed and rasped them to such a thinness in parts that he was able to free himself from them at any moment. He hoped that being in irons he would not be watched very closely, and intended, so soon as he had matured his plans, to shake them off and make his escape. Goodenough’s companion, King, who pleaded guilty at the last assizes, forms a high estimate of his ingenuity, for he says there is no building in England to keep him in, or keep him out.[13]

To Western Australia

On 3 July 1857 Goodenough, under the name ‘John Williams’ (Convict No. 4302), arrived at Fremantle onboard the Clara. He was described as aged 23, a carpenter, single, 5’4¼” tall, with brown hair, grey eyes, an oval face, a sallow complexion and middling stout, with a cut second knuckle on each hand.

His propensity for escape came to the fore in 1862:

A few days since a ticket-of-leave man named Williams, who was in confinement for

robbery in the Lock-up at Busselton, a building finished a few months since at a cost of

£1400, made his escape by picking out the mortar and stones from the wall under the

window of his cell. Williams was closely searched before being locked up, and therefore we may suppose the only implements he could have made use of were his fingers, which tells a queer tale as to the materials employed in the building.[14]

Later that year a Vasse correspondent wrote, on 16th instant: — The escaped convict Williams is down here again. He has had several skirmishes with the police, and I really think he would have been caught, long ere this, if his seekers were of the bravest. He has stolen a great many things from Colonel Molloy, Mr. John Bussell, and Mrs. Chapman. We heard he had gone away in an American whaleship, and were much surprised to find him still at the Vasse. The captain of the whaler wished to take him, but the mate would not hear of it. Really he is a most disagreeable neighbour, going about from house to house, stealing his way through the district. He has a revolver, and ammunition he supplies at the expense of the settlers.[15]

[Note: By this time John Williams had already left the colony in a whale-boat.]

Back in England

By 1864 Goodenough had somehow made his way back to England, where he used the name ‘Captain John Smith’ and was able to set up a comfortable establishment in Portsmouth, living on the proceeds of at least nine robberies in various parts of the country, in the company of a young man named Charles Stewart. He set his sister Harriet up in lodgings at Mrs Stewart’s house and used her as a conduit to various dealers in order to dispose of their stolen loot. The names of the two men were posted in the Police Gazette as wanted, but it was only by accident that they were finally found. A young man was walking in Windsor Great Park when his dog drew his attention to a bundle containing a large quantity of watches, some jewellery and silver. A woman was able to describe two men who had been acting suspiciously in the area and they were identified as Smith and Stewart. Word spread of the find and the two were able to make a quick getaway, only to be discovered later at the Red Lion Inn in Thorpe, the home town of Smith/Goodenough. Smith engaged in a violent struggle with the police, during which time he was beaten over the head with a baton, but still managed to escape. He was later apprehended and the two thieves were placed in the lock-up at Chertsey. It was said that on arrival and departure from the Chertsey Station House, between two and three hundred people stood cheering the police, glad to be rid of the person who had terrorised the neighbourhood.[16]

During his trial, Smith denied being Goodenough or Williams, stating that he was not an Englishman and had never been in the country prior to the arrival of his ship in Portsmouth.[17] However Harriet Goodenough identified Smith as her brother John Goodenough, after being charged with receiving stolen goods from him.

A Second Term in WA

Goodenough arrived back in the colony of Western Australia as ‘John Smith’ (Reg. No. 8998), on 4 July 1866, onboard the Belgravia.[18] He was described as a labourer, aged 30, single, 5’3” tall, with brown hair, grey eyes, a round face, sallow complexion, middling stout in build, and a scar on the bridge of his broken nose.[19]

Defiant till the end, John Goodenough, alias John Smith, was one of a group of nine convicts who broke out of Fremantle Prison in August 1867. Their escape was well-planned, with one of them dressed in a warder’s uniform, marching the others out through the inner gates as though on work duty. Smith/Williams/Goodenough was said to have been one of the ring-leaders:

DARING AND CLEVER ESCAPE OF NINE MEN FROM FREMANTLE PRISON.

WE have read in novels and romances strange accounts of improbable escapes from dungeons and other places of confinement, but fact is ever stronger than fiction, and the most improbable escape ever invented by novelist falls into the shade when compared with the actual occurrence that took place in this town the evening of Thursday the 8th inst. The coolness and self-possession of the contriver and carryer-out of the escape is astonishing, while the wrath and consternation among the officials when they discovered how successfully they had been done, may be better conceived than described. The particulars are as follows: Somewhere about ½ past 5 in the evening, after the prisoners had come in from the works, and the sentries had left the platforms on the prison walls, a person dressed in the uniform of a Warder passed out of the division in charge of eight men, deliberately unlocks the gates of the inner yard and passes through. He halts his men, and commands them, in the authoritative tones of an officer ‘not to be in such a hurry’.

The Warder coolly turns round, locks the gates, gives the word of command to his men and marches them into the workshop yard. A sentry notices them, but the uniform deceives him and they pass unchallenged. Once in the yard, they strongly barricade the gates, get out two ladders that had been carefully concealed in one of the shops, rear them against the wall; a rope is attached to the top rung of the ladder and let fall on the other side. The party mount the ladder one by one, and with the assistance of the rope drop outside and are off; while getting over the wall a Warder’s wife living near observes them and gives the alarm; her husband who happens to be in, discharges a pistol at them but without effect; they get clear off and up to this time nothing has been heard of them. The pretended Warder was the notorious convict John Smith, alias Williams, who escaped some years ago from the colony, went to England and receiving another sentence came back in the Corona [sic, Belgravia], was identified as an escaped prisoner and received an additional sentence.

The names of the men who accompanied him are: — James Billings, Edward Onions, Roderick O’Lacklon, William Stewart, Bernard Wootton, Walter Walker, William Watkins, James Sline [sic, Slim]. They have made tracks Southward and the police are upon their heels. Unless they have the good fortune of Moondyne Joe, Graham & his companion will soon be captured. There can be no doubt that the successful evasion of the police by these men tends to encourage escapes. It certainly does not give us a high opinion of the efficiency of the police for these men, unarmed and half-starved perhaps, to remain so long at large. The supposition that they are harbored by companions does not in any way account satisfactorily for their non-capture. Let us hope that by the speedy capture of these nine runaways the police will endeavour to restore confidence in their activity and intelligence, which we can assure them is becoming somewhat shaken.[20]

The following articles give further details of the events which followed the escape:

The Escape of Prisoners at Fremantle. — An official inquiry into the circumstances attending the late escape of Williams and eight other convicts has led to the dismissal of Mr. Assistant Superintendent Cook, to whose dereliction of duty the unfortunate escapade has been attributed. Five of the nine convicts who lately escaped front the prison at Fremantle were captured last week near Dundalup [sic], and, by last advices from Pinjarrah, Captain Fawcett and a party of the Pinjarrah Cavalry Volunteers were in pursuit of the others, who, judging from the direction of their tracks, were making for the hills.[21]

James Slim, one of the nine men who recently made their escape from the Fremantle Prison, has been captured at Mr. Prinsep’s establishment near Dardanup. When brought before the Resident Magistrate, he reported that his mate, the noted Williams, had been accidentally drowned while attempting to swim the Murray River. Such an accident is of course possible, but the source of information must be more authentic before it will be considered even probable. The police keep well on the move, evidently under the impression that their best chance is on terra firma.[22]

Intelligence has also reached Perth of the capture, on the Blackwood, of the convict Scott, who escaped with Graham. The body of Williams, the escaped convict, has been discovered in the Murray River. It was observed floating in the stream by a native, and afterwards identified by a gold ring on the small finger of the left hand. Williams is said to have been a good swimmer, and, no doubt, would have succeeded in crossing the river but for the encumbrance of his clothes, which were found strapped on his head.[23]

So ended the life of John Goodenough, at one stage likened to the legendary Jack Sheppard, an 18th century young thief and escape artist in England, much admired by the working class and whose exploits were later featured in poems, books and plays. It is not known where John Goodenough’s body was buried.

…………………………………………..

[1] Church of England Births & Baptisms 1813-1917, Bishop’s Transcripts.

[2] England & Wales Criminal Registers, Buckinghamshire, 1841, https://www.ancestry.co.uk

[3] Note: See Hector Fenner’s story on this website.

[4] Rosalind Crone, The Great Reading Experiment: An Examination of the Role of Education in the Nineteenth Century Gaols, Vol.16, No.1. 2012, Open Edition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/chs/1322

[5] Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HM_Prison Reading

[6] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 06 October 2020), October 1851, trial of JOHN GOODENOUGH (t18511027-1840).

[7] England & Wales Criminal Registers, Berkshire, 1854, https://www.ancestry.co.uk

[8] Wiltshire Independent, 19 July 1855.

[9] Hertford Mercury & Reformer, 8 December 1855.

[10] England & Wales Criminal Registers, Hertfordshire, 3 December 1855.

[11] Herts Guardian, Agricultural Journal & Advertiser, 8 December 1855.

[12] Ibid.

[13] West Middlesex Herald, 12 January 1856.

[14] Perth Gazette, 8 August 1862.

[15] Inquirer, 24 December 1862.

[16] Windsor & Eton Express, 16 April 1864.

[17] Salisbury & Winchester Journal, 28 May 1864.

[18] Western Australian Convicts, http://members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/con-wa39.html

[19] Ibid.

[20] Herald, 24 August 1867.

[21] Inquirer, 21 August 1867.

[22] Inquirer, 4 September 1867.

[23] Inquirer, 25 September 1867.