By Anne Kirkman, 2024.

GIROLAMO GIOVINAZZO [also spelt Giovinazza, Giovinzzo, Giovanazzo]

BORN: 9 October 1892, Cittanova, Calabria, Italy.[1]

PARENTS: Giuseppe GIOVINAZZO, baker and Teresa SCARPO; both deceased by 1940.

SIBLINGS: Four sisters and two brothers. One brother immigrated to New York, USA the other was married and living in Italy as were his four sisters.

MARRIAGE: 21 December 1922, Italy.

WIFE: Anna Maria LANDO, born 2 March 1905 Varapodio, Calabria, Italy, died 25 March 1980, buried Cheltenham, South Australia.[2]

CHILDREN: Giuseppe (Joe), born 13 August 1923 Varapodia, Calabria, Italy, died 23 December 2000, Adelaide, South Australia, buried Cheltenham, South Australia; Francesco, born 14 April 1926 Varapodia, died 1988, Baccus Marsh, Victoria, Australia, buried Cheltenham, South Australia; Teresa, born 14 January 1939 Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, died 16 September 1939, Kalgoorlie; Maria Teresa, born 26 November 1940 Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, died 9 October 2022, Adelaide, South Australia, buried Cheltenham, South Australia.[3],[4]

MILITARY SERVICE: 1912-1919 Italian Army 82nd Infantry.

OCCUPATION: Miner, 1908-1912 and 1919-1927

DEATH: 7 March 1941, No. 11 Internment Camp, Harvey, Western Australia.[5]

BURIAL: Harvey Cemetery, Western Australia. Exhumed 21 Feb 1961 to the National Memorial Cemetery, Murchison, Victoria, Australia (Italian Ossario).[6]

Girolamo Giovinazzo’s grave at Harvey Old Cemetery.

EARLY YEARS

Girolamo grew up in Cittanova, Calabria, Southern Italy. When aged fifteen a large earthquake shook the Calabria region followed by a devasting tsunami. Amid the desolation thousands lost their lives. It was the most destructive earthquake to strike Europe. Cittanova was spared the devastation but no doubt the Giovinazza family felt the shock and witnessed the damage. In the same year, Girolamo started work as a miner. Four years later he joined the Italian Army, 82nd Infantry, where he served from 1912 to 1919 after which he continued work as a miner. In 1922 he married Anna Maria Lando; a son was born in 1923 and another in 1926. During the 1920s and 1930s strikes and riots were commonplace in Italy due to political unrest and the poor economic conditions. The working man could not see a stable future, therefore many of them migrated to either America or Australia, known as chain migration.

Seeking better circumstances, like many of his compatriots, Girolamo left behind his wife and two sons, who he would not see again for ten years, and sailed to South Australia aboard the Regina d’Italia, landing at Port Adelaide on the 15 September 1927. His landing papers reveal he had been sponsored by Bagnato Carmelo of 200 Hindley Street, Adelaide.[7] Bagnato was a relative; perhaps he operated one of the several boarding houses on Hindley Street where other Italians offered fellow migrants reasonable priced board and lodgings, but there is no evidence of this or of the man himself. Girolamo spent seven years in South Australia, employed firstly as a gardener; where the pioneer Veneto migrants were establishing market gardens, close to the River Torrens.[8] Over the next four years he was employed as a stone crusher.

In 1934 Girolamo moved to the prosperous goldfields of Kalgoorlie, Western Australia where he resided at 48 Hopkins Street, Boulder, a short distance from Kalgoorlie. The nearby Lake View and Star Mine was the largest employer of labour on the Golden Mile and Girolamo was now back in his field of work.[9] In the same year the notorious Kalgoorlie riots wreaked havoc in and around Kalgoorlie and Boulder. The riots were largely the result of bad feelings against the Italian community after the death of an Australian man who had had an altercation with an Italian barman at the foreign-owned Home from Home Hotel, one of the first places raided by the angry rioters.[10]

The remains of Gianatti’s Home from Home Family Hotel, 1934.[11]

Some months on, the destruction was still uncleared and it would seem Girolamo was fortunate in finding accommodation, as much of the housing in Boulder had been destroyed.[12]

In August, a letter Girolamo penned was published in a Sydney-based Italian newspaper:

From Kalgoorlie. A Meeting Club. We receive and publish:

Dear Editor, I have been at Kalgoorlie for three weeks and note it is a very large area which is rich with gold mines but, although everyone is working and earning, there was no place for leisure and meeting, something much desired, especially after an outbreak of hatred gave rise in we foreigners the need to be more united and in agreement through more frequent contact.

This gap has now been filled thanks to the goodwill off the Company and especially through the work initiated by fellow countryman Antonio Monteleone, who has been able to get a Meeting Room, to which has been added the name ‘Goldfield Club’, at 295 Hannan St.

As a result of being given some hours of honest and pleasant leisure among our best and good compatriots when we finish our daily work, one feels a strong nostalgia for our people and our beautiful language.

Before, we were lost and lonely like the hermits of the Madonna of Polsi Convent in the Valley of Aspromonte in our bountiful and strong Calabria.

From all your compatriots at Kalgoorlie, greetings to the Giornale dei Italiani (Italians’ Newspaper).

Giralomo Giovanazzo, Kalgoorlie, 8 August.[13]

The shocking riots that had occurred earlier in the year were forgotten for one day in October, when the Duke of Gloucester visited the goldfields. Large crowds gathered on the streets, including school children who were given the day off, all hoping to catch a glimpse of the royal visitor. Included in the day’s busy itinerary was a trip to the largest mine on the goldfields, Lake View and Star, Girolamo’s place of work, so it is possible that he caught a glimpse of the Royal visitor. It was not planned for the Duke to go underground but he donned overalls and inspected the workings. After watching a gold pour, management presented him with a miniature gold brick. At day’s end, the Royal train departed for Port Augusta, South Australia.[14]

Four years on, Girolamo’s wife and children landed at Fremantle port, Western Australia, aboard the Remo from Genoa. The children, a boy aged fourteen years and another aged eleven possibly felt apprehensive about meeting their father who they hardly remembered. A year later Teresa was born – sadly, she died at 8 months. Another child was born in 1940, named Maria, who likely would never meet her father.[15] Difficult times were ahead for their mother, Maria.

INTERNMENT

When Italy entered the Second World War with Germany on 10 June 1940, Italians were deemed a threat to Australia’s security and were rounded up and placed in internment camps.[16] The Remo docked at Fremantle on 10 June 1940 and was seized the following day.[17] Officers were transferred to Fremantle Prison while the crew were transferred to an internment camp on Rottnest Island. On 24 and 25th September 1940, officers and crew were transferred to Harvey Internment Camp. [‘The seized ship, Remo was renamed Reynella and was used to transport food-stuff and war materials from Australia to Britain. By 1949 Reynella was no longer suitable for Australian service and was sold to an Italian shipping company where it returned to its original name.’[18]]

Likewise, Italian men were being rounded up in Kalgoorlie, Boulder and surrounding districts. For the many Italians who lived and worked there this must have been unwelcome news, but the men were compliant, with many offering themselves up to police. They were kept under military guard whilst awaiting their transfer to Perth.[19] On the transfer to Perth the body of an internee was found in the lavatory of the train. His death was self-inflicted, not only was this tragic but distressing for all.[20] ‘Those who faced immediate internment included not only those who were suspected of espionage or of belonging to Communist or Fascist organisations, but also those whose occupations were thought to offer any opportunity whatsoever for espionage or sabotage’.[21]

Included in the round up were Girolamo and his son Giuseppe. On 6 July 1940, Girolamo expressed his concern of the internment of his 16-year-old son by writing to the authorities requesting his release. Future correspondence had no mention of Giuseppe therefore it can be assumed he was released.[22]

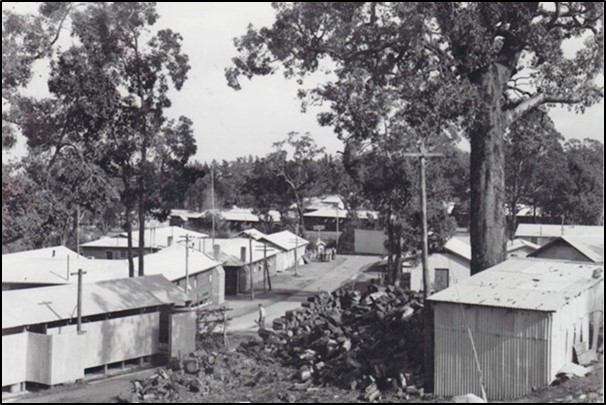

View of the 3rd Australian Corps Training School taken October 1942, formerly the Harvey Internment Camp. Australian War Museum, accession number 027160

Approximately four months was spent on Rottnest Island before the internees were conveyed to the Harvey encampment located outside the Harvey township on approximately 65 acres of land,[23] of which a portion had been the Harvey Golf Club.[24] The Harvey Camp operated from September 1940 until April 1942, after which the internees were relocated to Loveday Camp in South Australia. Thereafter the Harvey Camp was used as an Army Training School and at war’s end became a Rural Training Centre for ex-serviceman.[25] In 1953 the Agricultural Wing of the Harvey Junior High School was opened on the site.[26]

On the 27 November, 1940 the Minister for the Army, Sir Percy Spender, notified all states of Australia that applications would be made available for all those persons interned to appeal and that tribunals would be set up to consider applications.[27]

Antonio Dorazio wrote to officials on behalf of Maria, asking that consideration be given to the release of Girolamo from the internment camp. Antonio stated that he would employ Girolamo on his mixed farm (poultry, pigs, etc.) at Maddington and would provide accommodation for the family. This was followed up by Maria’s hand-written letter dated 30 October 1940, also requesting the release of her husband. She stated that she was due to have a baby, had no means of income, was not receiving any government aid and was certain her husband would have work if he was released. In the reply four months later, 24 February 1941, the Tribunal declined his release on the grounds that he was a security risk and had not yet applied for citizenship, having lived in Australia for 13 years.[28] Perhaps the authorities were justified in their hesitancy; on a concrete block as part of his grave, the words ‘INTERNMENT CAMP, HARVEY. 7-3-41. A. XIX’ are engraved. [A. XIX is the Era Fascista for 1941.[29]]

An appeal was put forward and on 17 March, Antonio received mail stating that Girolamo would be granted release by the Tribunal, subject to suitable employment being arranged. An application was included for Antonio to confirm and sign. Regrettably this never happened, as ten days earlier on 7 March, Girolamo had died suddenly at the Internment Camp.[30] There were no suspicious circumstances as his death was due to natural causes.[31]

Girolamo was buried at the Old Harvey Cemetery. On 21 February 1961 his remains were exhumed and conveyed to the National Memorial Cemetery, Murchison, Victoria, Australia.[32] It is the only Australian war cemetery dedicated to Italian civilian internees and Prisoners of War (POWs) who died in Australia.[33]

MARIA

A notification in the Kalgoorlie Miner, December 1948, reported Maria Giovinazzo’s application for naturalisation.[34] Additional information states citizenship was granted and she was living at 37 King Street, Boulder, with her two adult children and her youngest child, Maria.[35] When Girolamo’s wife left Boulder is unknown, but her grave is located at Cheltenham Cemetery, South Australia. Her headstone names her three children, their wives and husband. The other names engraved are probably her grandchildren.[36]

Maria Giovinazzo’s grave, Cheltenham Cemetery, Adelaide

In contrast, the untended grave at Harvey of her husband Girolamo has a headstone that reveals little of the man who was buried there. This is his story.

………………………………………………………..

[1] NAA: D4880, Italian/Giovinazzo.

[2] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ryerson Index at https://www.ryersonindex.org

[5] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[6] Harvey History Online at https://www.harveyhistoryonline.com

[7] NAA: D4880, Italian/Giovinazzo.

[8] Venetimarketgardeners1927.net

[9] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[10] Mercury, 7 February 1934, p. 11

[11] Wine Saloon, Home from Home Hotel and All Nations Hotel all within a stone;s throw of one another looted and destroyed by fire. The photo shows the remains of (Gianetti’s) Home From Home Hotel, Kalgoorlie [picture] Published/produced 1934, 001505D, State Library of Western Australia.

[12] The Weekly Gazette February 9 1934, p.5

[13] Il Giornale Italiano (Sydney, NSW : 1932 – 1940), ‘Da Kalgoorlie Un Club Di Riuione’, 15 August 1934, p.2, transcribed by Janice Calcei.

[14] Singleton Argus, 10 October, 1934 p.1

[15] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[16] Kalgoorlie Miner, 12 June 1940, p.4

[17] West Australian, 12 June 1940, p.11.

[18] https://italianprisonersofwar.com/tag/italian-motorship-remo accessed 31 January 2024

[19] Kalgoorlie Miner, 12 June 1940, p.4

[20] West Australian, 15 June, 1940 p.16

[21] Extract Hansard Assembly, 20 June 2012, p.100a-4117a

[22] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[23] Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 26 June 1941, [Issue No.124], p.1367

[24] Harvey Times, 28 February 1946, p.6

[25] Reflections Within the Harvey Shire, researched and compiled by Kerry Davis… [et al.] Harvey Visitor Centre and Harvey History Online, Harvey, WA.

[26] Harvey Murray Times, 31 December 1953, p. 1.

[27] West Australian, 28 November 1940, p.8

[28] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Era_Fascista, accessed 27 November 2023. The Era Fascista (“Fascist Era”) was a calendar era (year numbering) used in Fascist Italy. The March on Rome, or more precisely the accession of Mussolini as prime minister on 29 October 1922, is day 1 of Anno I of the Era Fascista. The calendar was introduced in 1926 and became official in Anno V (1927).[1] Each year of the Era Fascista was an Anno Fascista, abbreviated A.F. The Era Fascista year was sometimes written as “Anno XIX“, “A. XIX“, or marked “E.F.” The calendar was abandoned in most of Italy with the fall of the Fascist regime in 1943 (Anno XXI), but continued to be used in the rump Republic of Salò until the death of Mussolini in April 1945 (Anno XXIII).Many monuments in Italy still bear Era Fascista dates.

[30] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[31] South Western Times, 14 March 1941, p.1

[32] Harvey History Online at https://www.harveyhistoryonline.com/

[33] https://sheppandgv.com.au/listing/italian-ossario-1131

[34] Kalgoorlie Miner, 29 December 1948, p.3

[35] NAA: PP302/1, WA28427, Giovinazzo, Anna Maria.

[36] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/100575729/anna-maria-giovinazzo