[Story by Rosalie D Ali, with added information from Irma Walter & Heather Wade, 2021.]

Early Life

James Wynn’s parentage is not known. His convict records have him born in Surrey, England, in 1842. The birth of a James Wynne was recorded in the June Quarter of 1842 in the St George South District of Southwark.[1] The only evidence of a possible relative was a person who visited him later in Portland Prison, registered as his next-of-kin, under the name Elizabeth Shaw, of 15 Charlotte St, Blackfriars’ Road. [Other visitors on the page were described as ‘Father’, or ‘Mother’ etc., but no such relationship accompanies Elizabeth Shaw’s name.][2]

These days, thousands of tourists flock to this part of London because of its cultural attractions, which include the Globe Theatre and the Tate Gallery. However in the mid-nineteenth century it was said to be one of the most disreputable parts of the metropolis, the haunt of criminals and prostitutes.

Little is known about James’s early years. Records show that from September 1850 he lived for three years in the St George the Saviour District Workhouse on Mint Street, in the Parish of St George the Martyr, on the southern side of the Thames near London Bridge in Surrey. The admittance sheet shows that he was one of a group of eleven boys admitted from Lewisham (near Greenwich).[3] They were probably waifs with no visible means of support, picked up off the streets.

Life in the Workhouse

A brick workhouse was first built in Mint Street in 1729, for receiving and employing the poor of the Parish. According to a report dated 1731, at that time there were ‘68 Men, Women and Children, of which all that are able, spin Mop-yarn and Yarn for Stockings, all knit by the Women; and beside this work, 25 Children are taught to read and say their Catechisms.’ Inmates were reimbursed one penny for every shilling they earned.[4]

As the need for such institutions grew, more buildings were added to the Mint Street site. By the mid-nineteenth century most boroughs had their own workhouses or shared one in a union with neighbouring parishes. They were institutions where sick and destitute people were provided with the basics, funded by taxes raised from local taxpayers. Only the most desperate cases were admitted, with many turned away from the doors.

In 1865 a critical report into London workhouses was published over several editions in the Lancet Medical Journal. The St George the Saviour district at this time was a most unsavory place to live. It was described in the report as ‘a densely populated area, with a population of 55 000, surrounded by every kind of nuisance, physical and moral. Bone boilers, grease and cat-gut manufacturers represent some of them, and there is a nest of thieves which has existed ever since the days of Edward III.’[5]

The Lancet investigation into the St George the Saviour Workhouse, situated in the Parish of St George the Martyr, revealed gross deficiencies. It found that although the workhouse was built to accommodate 624 inmates, that even with 420 in residence at the time of the survey, it was obviously overcrowded. An average of four children slept in each bed. A ward of 30 men shared only one closet (toilet) with no water supply, and an overwhelming stench of ammonia pervaded the place. The so-called ‘tramp ward’ for women, with straw on the floor, was described as ‘a den of horrors and a perfect fever bed’, their only toilet facility being a large can in the middle of the room.

Fevers and plagues such as typhoid spread rapidly through the local population and into the workhouse, where medical care was mostly in the hands of pauper nurses, on low rates of pay and frequently drunk, with little understanding of the basic rules of hygiene. They admitted using chamber pots as utensils for washing patients.[6]

Life in a workhouse was not meant to be easy or enjoyable. The sooner an inmate was discharged, either back onto the street, or in a coffin to the graveyard, the sooner another needy individual could be accommodated. There was an average of 300 deaths per year in this institution.

Within the St George the Saviour Workhouse there were seven different sections, with boundaries strictly enforced. Each had their own ward, with a fenced-off yard. Men and women, young and old, were separated. Catering mainly for the sick and the elderly, the workhouse was not an ideal place for raising children. Those who arrived as a family unit were hardly allowed any shared time with their parents. Boys aged between seven and fifteen were in one section, while younger boys were in another. Some schooling was part of the day’s program. Those fit enough to work were expected to do so. Similar to the practice in prisons, the work was tedious and repetitive, such as crushing rocks, sorting wool or picking oakum, a task which involved untwisting old sections of rope, for use in plugging up gaps in the decks of naval ships. The food was limited in quantity and monotonous in variety.[7]

The novelist Charles Dickens, who had lived through some difficult years himself as a child when his family was incarcerated in a debtors’ prison, campaigned vigorously for children’s rights. At one stage his family lived quite close to a major London workhouse, so he would have been aware of the suffering taking place there.[8] The inspiration for his character Oliver Twist is said to have come from such a workhouse, which Dickens considered ‘an abode of enduring misery’. The phrase ‘Please, sir, I want some more,’ became synonymous with the plight of so many children of that era.

‘Please, sir, I want some more.’ (Etching by George Cruikshank)[9]

‘Please, sir, I want some more.’ (Etching by George Cruikshank)[9]

James Wynn was discharged from the workhouse at the age of eleven, in 1853. There was an outbreak of ‘Asiatic Cholera’ in the workhouse that year.[10] Alone on the streets of a sprawling metropolis like London James would have had a hand-to-mouth existence. He must have been resourceful, because he somehow survived, probably by committing petty crimes such as pick-pocketing. He also learnt a trade. A record shows that by the age of 17 James was a shoemaker, able to read and write imperfectly.[11]

A Foolish Crime

By then James had graduated to more serious crimes. Along with two brothers, Stanley (15), and William Selway (16), James Wynn, aged 17, was charged with robbery with violence from the shop of a picture frame dealer, Mr Dear, of 49 Essex Street, the Strand, London. The raid was obviously planned, with James leaving his lodging house with a chisel as a weapon, after arranging for William to meet him at Mr Dear’s premises.

It was a foolish scheme from the start. Stanley Selway was an employee of the shop’s owner, and had been told that his employment was to be terminated at the end of the week. On the day of the robbery Mr Dear, who had been paralysed for three years, was resting on a sofa, when Stanley Selway entered the room with James Wynn, saying that his friend would like to apply for the job. When asked about his qualifications, Wynn said that he had previously been employed in the book trade. [Mr Dear later described Wynn as ‘pale and cadaverous, and not respectably attired.’] While they were discussing the position, Stanley forced open a cupboard in the room and grabbed a cashbox and its contents, valued at £1/6/-. James Wynn was said to have struck the shop owner twice over the head with the chisel before running off. A crowd quickly gathered and it wasn’t long before the Selway brothers were located and arrested.

Instead of lying low, James Wynn went to the prison a few days later, intending to visit the two brothers. He was recognized by a policeman as a co-offender and was taken into custody.

Following his arrest James admitted his involvement in the crime, telling the police that he had only hit the old man once, and that William Selway had nothing to do with the robbery. When the three faced trial at the Central Criminal Court on 9 May 1859, James Wynn pleaded guilty to the charge of robbery with violence. A policeman gave evidence that James had previously been convicted at the Bow Street Police Court, on his own confession, of stealing £2/15/- from his mistress, and was confined for two months.[12] With this previous conviction taken into account, James was sentenced to ten years’ transportation.[13] William Selway was acquitted and his brother Stanley was sentenced to four years’ penal servitude.[14]

James served approximately two-and-a-half years in four different prisons, Pentonville, Millbank, Newgate and Portland. His conduct was noted as ‘Very Good’.[15] He was transported on the convict ship Palmerston to Western Australia, leaving Portland on 10 November 1860 and arriving at Fremantle on 11 February 1861. James was one of 296 convicts transported on that ship.[16]

On arrival James was described as aged 18, a shoemaker, single, Protestant, 5’2”, with light brown hair, light brown eyes, an oval face, fair complexion, and of stout build. He had a slight scar on the right side of his neck, otherwise no markings. His belongings brought with him from the ship were listed as letters, a photograph, tobacco, a knife and a leather belt.[17]

Life in WA

James was a good worker, determined to make the most of the opportunity of a fresh start in a new country. He mostly kept out of trouble, apart from a punishment of two days on bread & water while in prison and later a couple of charges of drunkenness in Bunbury. His record in WA reads as follows —

27/2/61 – Four months’ remission by His Excellency the Governor.

1/11/61 – Was at Guildford.[18]

4/7/62 – A further 15 months’ remission.[19]

11/9/62 – To Bunbury from CE. (Convict Establishment).[20]

11/9/62 – Received his Ticket of Leave.

11/7/65 – Convicted by George Eliot, RM Bunbury, of being drunk and resisting arrest – fined 10/-.

20/8/66 – Being drunk – 21 days in Depot. Assaulting police, etc., – one month’s hard labour.

10/11/66 – May apply (for his Ticket of Leave?) in August 1867 if no further reports.

17/1/67 – At Bunbury Depot. Losing his Ticket of Leave.[21]

15/2/67 – Ticket of Leave and Police Record sent to Bunbury.

26/2/67 – At CE. (Convict Establishment).[22]

7/12/67 – Conditional Pardon to Resident Magistrate, Bunbury.[23]

Employment in the Wellington District

After receiving his Ticket of Leave certificate, James was then free to seek employment in the fledgling settlements around Bunbury and Australind, where he was employed as a laborer and shoemaker by a variety of land and business owners in the district. Four of his employers were former convicts:

Date, Residence, Employer, Occupation, District

30 June 1863, Rosamel, Piggott, Labourer, Bunbury

31 December 1863, Rosamel, Piggott, Labourer, Wellington

30 June 1864, Rosamel, Piggott, Labourer, Wellington

31 December 1864, Rosamel, Piggott, Shoemaker, Wellington

1 April 1865, Picton, W Calfe, Shoemaker, Wellington[24]

30 June 1865, Bunbury, Piggott, Labourer, Wellington

3 December 1865, Bunbury, Jas. Piggott, Shoemaker, Bunbury

30 June 1866, Bunbury, EG Hester, Shoemaker, Bunbury

11 October 1866, Australind, Frank Travers, Bootmaker, Bunbury[25]

27 December 1866, Bunbury, William Weir, Shoemaker, Wellington[26]

31 December 1866, Bunbury, F Travers, Shoemaker, Wellington

31 January 1867, Bunbury, M Mackay, Shoemaker, Wellington[27]

30 June 1867, Bunbury, M MacKay, Shoemaker, Wellington

27 July 1867, Australind, Jas. Piggott, Shoemaker, Wellington[28]

Marriage and Family

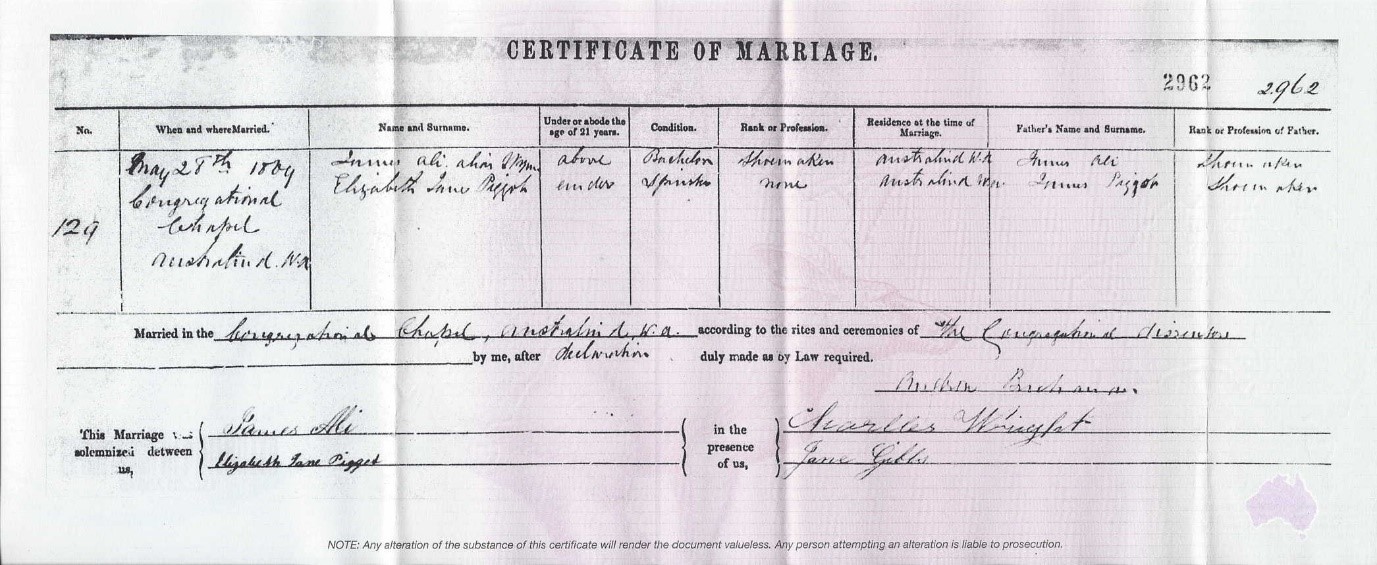

On 28 May 1869, James Wynn married Elizabeth Jane, the eldest daughter of James Piggott and Johanna Piggott (née Simmons), at the Congregational Chapel in Australind, near Bunbury. In the Congregational Church notes, the Rev. Andrew Buchanan recorded that Elizabeth was the daughter of James Piggott, shoemaker, of Ditchingham Cottage at Australind, so he may still have been James’s employer.

Their marriage certificate shows his name as ‘James Ali, alias Wynn.’ The witnesses were Charles Wright and Jane Gibbs.[29] [The tiny church still exists and is now known as the Church of St. Nicholas.]

Marriage Certificate of James Ali and Elizabeth Piggott.

[It is of note that at the time of his marriage James Wynn was using the name ‘James Ali’, so his wife Elizabeth was always known as ‘Mrs. Ali’. No-one knows the reason for the name change. It may have been an attempt to distance himself from his convict past. His descendants have kept the name ‘Ali’, pronounced as ‘Ay-ligh’.]

James established a shoemaking and tanning business of his own in Bunbury and Australind. By 1874 ‘Ali & Co.’ was advertising in the Herald Almanack as tanners in Bunbury, and in the same year in the W.A. Almanack as shoemakers and tanners in Bunbury and Australind.[30] He employed twelve men between 1868 and 1873 – 7 T/L shoemakers and 5 T/L labourers and servants.[31]

By 1877 James was listed variously as a farmer, shoemaker and tanner of Bunbury, or of ‘Bunbury and Suburbs’.[32] James wasn’t the only ex-convict shoemaker in the area. William Calfe (Reg. No. 2710), also in the tanning business, Frank Travers (Reg. No. 3920), Michael Mackey (Reg. No. 2322), Charles Wright (Reg. No. 6762) and William Weir (Reg. No. 5934) were also former convicts in the trade.

Just where James Ali’s tannery premises were situated is not known. However, due to the large quantity of water needed in the tanning process, it was probably situated near the Bunbury Estuary. His house was probably next to his workplace. The smell from the skins would have made life difficult for the family and neighbours.

[Note: James Lambe, a former tanner operating in Bunbury in the 1880s, returned there in 1893, announcing that he intended to re-establish his business on ‘the premises formerly occupied by James Wynn’.[33]]

A newspaper article in January 1878 described James’s part in the rescue of a party of about sixteen people who were in one of three boats in the estuary near Bunbury, returning from a picnic. One of the boats capsized and James is said to have rushed from his house and ‘rendered material and praiseworthy assistance’ after hearing cries for help. Apparently, it was not the first occasion on which he has done so.[34] However, a later article corrected the story, saying that Mr James Ali was in a nearby boat ‘some distance off’. At least five men were recognized for their action in saving lives that day.[35]

In 1882 J Ali was listed as a member of Bunbury Temperance Society, ’Light of the South Lodge No. 16’.[36] Membership of a temperance society was popular at that time, when excessive drinking was a regular pastime of working men and was seen as a blight on the community.

To South Australia

Many ex-convicts were desperate to leave Western Australia, which was still struggling economically when compared with the Eastern colonies. Some succeeded in leaving WA before their term had expired, assuming a new identity and taking up a life of crime. Authorities in the East were increasingly alarmed at the arrival of undesirable characters on their shores. A permit system was devised, whereby an individual was obliged to carry a certificate indicating that he was free to leave Western Australia.

James Ali, well aware of the ‘convict stain’ which hung over his family, and eager to seek new opportunities for his children, made the decision to take them to the free colony of South Australia. By this time James and Elizabeth had quite a large family:

Elizabeth, possibly born on 29 May 1869. (She died in 1952).

Minnie, 1871–1952

Johanna, 1873–1943

Robert Leonard, 1875–1925

Joseph, 1877–1920

Charles, 1880–1962

James Edgar, 1882–1884, died of measles

William, 1885–1947

George Wilfred 1888–1888

Albert Ernest, 1890–1964, the only child born in South Australia.

In 1888 James advertised his Bunbury property for sale:

FOR SALE.

(OWNER LEAVING COLONY.)

ELIGIBLE FREEHOLD

PROPERTY

fronting Stirling Street, Bunbury, consisting of a Dwelling House, letting for £10 per annum; two roomed weather-board Cottage, galvanized roof, now used as a Workshop ; the House occupied by the undersigned with good brick oven and kitchen garden ¼ acre, well fenced and slabbed; Tan Shed 34 feet long by 14 feet wide ; four Tan pits under a “Lean-to” against the Shed; Lime Pit, with necessary tools; Stable, Trap House, Pig Sties, and a Pump and good supply of soft water, the whole situate on about 2½ acres of ground, well fenced;

This affords an excellent opportunity for any one desirous of possessing a

GOOD TANNERY,

as the premises are in a commanding position, being within easy distance of Harvey, Benger, Collie, Brunswick and Coast Road. Price £300.

For full particulars, apply to this office or to James Ali.[37]

Another notice was posted a week later:

NOTICE

AS I shall very shortly be leaving this Colony, I take this opportunity of thanking my Customers for their liberal patronage during the past 20 years, and shall be glad to receive all outstanding Accounts on or before the end of November, certain.

JAMES ALI.

Bunbury, October 23rd, 1888.

On 4 January 1889 James took his wife and the seven surviving children on the SS South Australian, to Adelaide and resettled there. James’s convict number (5838) and original name were handwritten on the passenger list.[38] It was not easy to leave a convict past behind, as although having a Conditional Pardon, he would have needed to carry a permit to enter South Australia.

Once in Adelaide, it is not known whether he initially took up his trade. He eventually became a house and commission agent in Grote Street, Adelaide. Originally living at Parkside and Unley, the family later moved to the Adelaide suburb of Hyde Park. [He owned two houses in King William Road.[39]]

In 1902 and 1903 James and several of his sons are listed in the Australia, City Directories, 1845–1948:

Jas. Ali, Leicester Street

Jos. (Joseph) Ali, Charles Street, Unley-North Unley,

Robert Ali, bootmaker

James Ali, commission agent, Arthur Street, Unley, SA/Unley Road, Unley Park, SA.

Joseph Ali, painter, George Street, Parkside, SA

James Ali, Coms. Agent, Leicester Street, Parkside, SA.

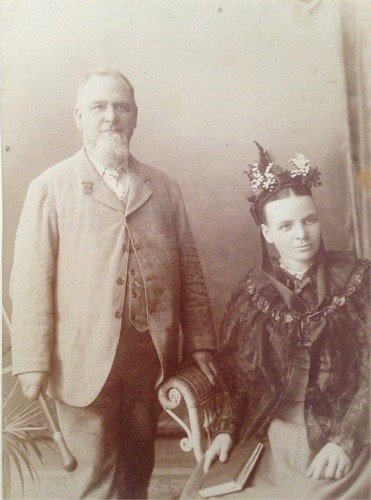

James and Elizabeth Ali, Stump & Co Studio, Adelaide. At the top of the cane that James is holding are his embossed initials – see photo below.

James and Elizabeth Ali, Stump & Co Studio, Adelaide. At the top of the cane that James is holding are his embossed initials – see photo below.

James’s wife, Elizabeth Jane Ali, passed away on 3 May 1912. The fifty-nine-year-old collapsed while serving tea at home:

FATALITIES AND ACCIDENTS.

DIED AT THE TEA-TABLE.

The police have received a report that on Friday evening, while Mrs. Elizabeth J. Ali, aged 59 years, wife of Mr. James Ali, agent, of Leicester-street, Parkside, was standing at the table serving the tea, she suddenly fell forward and lapsed into unconsciousness. Her son went to her assistance. Dr. Carr was called in, but he found that death had ensued from heart failure.[40]

Elizabeth Ali was buried in the West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide.[41]

The loss of their wife and mother at a relatively early age must have hit James and his family hard. She had been a loyal and supportive partner, but as with a lot of settlers’ daughters, life was physically hard, childbearing was constant, and household drudgery never ending.

As a house and commission agent, James Ali sometimes became embroiled in unsavory situations. In 1912, in an article entitled ‘Deserted Wives: Allegation of Misconduct Proved’, James was witness to the fact a man named O’Loughlin and Annie Norgen were living together in a home in George Street, Parkside, from 26 October 1911, to 26 February 1912. This was part of a divorce case where the wife cited desertion and adultery. The house was one that James visited in order to collect rent. Mrs O’Loughlin was living elsewhere.[42]

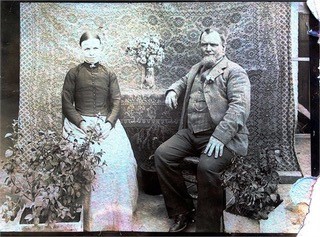

Elizabeth and James Ali.

At the end of an eventful life, James Wynn (alias Ali), died on 3 December 1915 at his home at Hyde Park in Adelaide, aged 72. He would have been proud that from poor beginnings he had established a successful business and provided well for his wife and large family. A brief family notice reads as follows:

DEATHS.

ALI – On the 3rd December, at King William road, Hyde Park, James Ali, beloved husband

of the late Elizabeth Jane Ali, aged 72 years and 10 months. At rest. W.A. papers please copy.[43]

James was buried at the West Terrace Cemetery, alongside his beloved wife.

Elizabeth and James Ali’s grave, West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide.[44]

The following announcement indicates that James Ali was a relatively prosperous businessman:

LEFT MONEY.

The current issue of the Weekly Gazette of the Mercantile Trade Protection Association records the following wills: Probates. — James Ali, Hyde Park, £1,700.[45]

Addendum from his g-grand-daughter Rosalie Ali in 2021 —

The workshop and house on one block and the adjoining house were both passed on to the Ali family, probably Charles, and provided homes for family members until the 1950s. Charles, still working as a carpenter, had his name and occupation displayed on the windows of a workshop at 168 King William Road, Hyde Park. Our family owned the properties until about the early 1960s. Widower Charles Ali, died in 1962, having lost his wife, Edith May (‘Maisie’) in 1953.

As we know, James’s sons, Joseph and Albert (‘Ernie’), were painters, and Robert a bootmaker. Albert served in the AIF in WW1, enlisting at the age of twenty-eight and serving from 1916-1920.

The Ali name lives on. We are not a huge family but it’s still growing, and the Ali males are carrying on the name.

……………………………………………..

[1] UK Births, Deaths & Marriages, Vol.4, Page 430, https://www.freebmd.org.uk

[2] UK Prison Commission Records, Registers of Prisoners. Millbank and Portland Prisons.

[3] Christchurch Workhouse Register, Southwark, 1849-50, https://www.ancestry.com.au

[4] The Workhouse – The story of an institution ….,http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Southwark/

[5] The Lancet Reports on Workhouse Infirmaries 1865-7, http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Lancet/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ruth Richardson, Oliver Twist and The Workhouse, 2014 at https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/oliver-twist-and-the-workhouse

[9] https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/illustrations-web/Oliver-Twist/Oliver-Twist-02.jpg

[10] Freeman’s Journal, 15 September 1853.

[11] Central Criminal Court After-trial Calendar of Prisoners.

[12] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, May 1859, trial of STANLEY CHARLES SELWAY (15) SAMUEL WILLIAM SELWAY (16) JAMES WYNNE (17) (t18590509-514).

[13]Ibid.

[14] Globe, 14 May 1859.

[15] UK, Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951.

[16] Convict Records, https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/palmerston/1860

[17] Convict Departments Estimates & Convict Lists, (128/1-32)

[18] Convict Department Registers, Probation Register (R7)

[19] Convict Department Registers, Probation Register (R7)

[20] Convict Department Registers, Probation Register (R7)

[21] Convict Department, General Register (R3-R4)

[22] Convict Department Registers, Probation Register (R7)

[23] Convict Department, General Register (R3-R4)

[24] Convict shoe-maker William Calfe. Currier at Bunbury in 1869. (Reg. No. 2710)

[25] Convict shoe-maker Frank Travers (Reg. No. 3920)

[26] Convict shoe-maker William Weir (Reg. No. 5934)

[27] Convict shoe-maker Michael Mackey (Reg. No. 2322)

[28] Convict Department Registers, General Register (R3-R4)

[29] WA Department of Justice, Marriage Reg. No. 2962, https://bdm.justice.wa.gov.au

[30] Carnamah Historical Society and Museum, https://www.carnamah.com.au/

[31] Brian Rose’s Index Card. This varies from the Bicentennial Dictionary by Rica Erickson, p.3405 which states that Ali employed a T/L labourer at Australind in 1870.

[32] Carnamah Historical Society and Museum, https://www.carnamah.com.au/

[33] Bunbury Herald, 7 June 1893.

[34] Herald, (Fremantle), 12 January 1878.

[35] Herald, 2 February 1878.

[36] Christian Herald, 24 August 1882.

[37] Southern Times (Bunbury, WA), 16 October 1888.

[38] SRO of Western Australia; Albany Inwards from Freemantle 1873-1929; Accession:108; Item:7; Roll:85,

https://www.ancestry.com.au/

[39] Note: His great-grand-daughter Rosalie Ali remembers staying there with her maternal grandmother who lived there for several years.

[40] The Advertiser, 6 May 1912.

[41] https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2232060/west-terrace-cemetery

[42] The Advertiser, Wednesday 4 September, 1912.

[43] The Register, 4 December 1915.

[44] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/150018661/james-ali

[45] The Register, 25 December 1915.