Written by Harry’s grandson Morgan Smith. Transcribed with extra material by Jeffrey Bentley-Johnston, 2018. Added to and edited by Heather Wade, 2022.

Henry Smith, otherwise known as ‘Harry Smith’ or ‘Big Smith’, was well-known in the timber industry as the Manager of Mornington Mills, the position he held from 1898 when it was built, to his death in 1937.

He was actually a Norwegian, born in Rygge, Ostfold, Norway on 25 August 1860 to Jorgen Jensen, a tenant farmer, and Kari Knudsdatter in the locality of Husbye.[1] On his christening record he is named Christian Jensen but in the 1875 Norwegian Census he is recorded as Kristian Jorgensen.[2] It is the same person. [Until the 1860s the Norwegians used the patronymic naming system, but for some reason the family used Jensen for births and christenings, the surname of their father.] Christian Jensen was a common name in Norway so when he came to Australia he changed his name to an equally common one – Henry Smith.

According to family history from relatives in Iowa, USA, Christian was apprenticed to a sea captain by his father, roaming the world in sailing ships and reputed to have been shipwrecked three times. Once was in the Gulf of Mexico on Key West when he saved the captain’s wife by wrapping her in his large overcoat after swimming ashore with her. He was suitably rewarded by the ship’s company and the local townspeople. [There is a relatively short period of time for all this to happen – in the 1875 Census of Norway conducted in December, Christian was still living with his parents and siblings at Rygge and was described as an agricultural worker. Jens, his brother, born 1852, was listed as a seaman. Harry’s obituary in the Harvey Murray Times, 9 April 1937, states that he ‘arrived in South Australia when 18 years of age’. Ed]

He was a giant of a man. It was recorded that Harry was known as ‘Big Harry’ or ‘Big Smith’ because of his size. He was 6’5” (196 cm) and weighed in later years 22 to 25 stone (139-158kgs).

As ‘Henry Smith’, Christian Jensen married Mathilda Hulda Mattner (known as Hulda) at the United Methodist Church in Adelaide on 6 August 1883 when he was 23. Hulda was born in 1863 at Harrogate, SA, to Carl Wilhelm Mattner, a wheelwright and Pauline Marks.

Harry and Hulda had the following children:

- Augusta Clara was born whilst they were in Naracoorte, 7 July 1884; she married John Cuthbert Teschemaker-Shute.

- Edith Hulda, born 11 August 1885, Adelaide; married Dr Llewellyn Bentley Lancaster [See ‘Yarloop Doctors’ on this website].

- Matilda Mary, born 3 October 1887, Albany; married Rev. Reginald Eugene Chapman.

- Emily Elizabeth, born 15 June 1889, Albany; died 16 June 1890, Denmark.

- Henry William, born 28 March 1893, Torbay; married Leila Clarice Ainsworth.

- George Charles, born 23 January 1895, Torbay; married Marguerita Elsie Ray.

- James Mattner, born 1 May 1897, Denmark; married Ada Isabella Janet Holtfreter.

- Grace May, born 12 November 1899, Mornington; married Ernest Thorley Loton (later Sir).

By June 1889 when Emily Elizabeth was born, the family was living in Albany. They had moved to a new house in Denmark where Emily died on 16 June 1890. We have not been able to find her grave in Albany. No burials occurred in Denmark at that time.

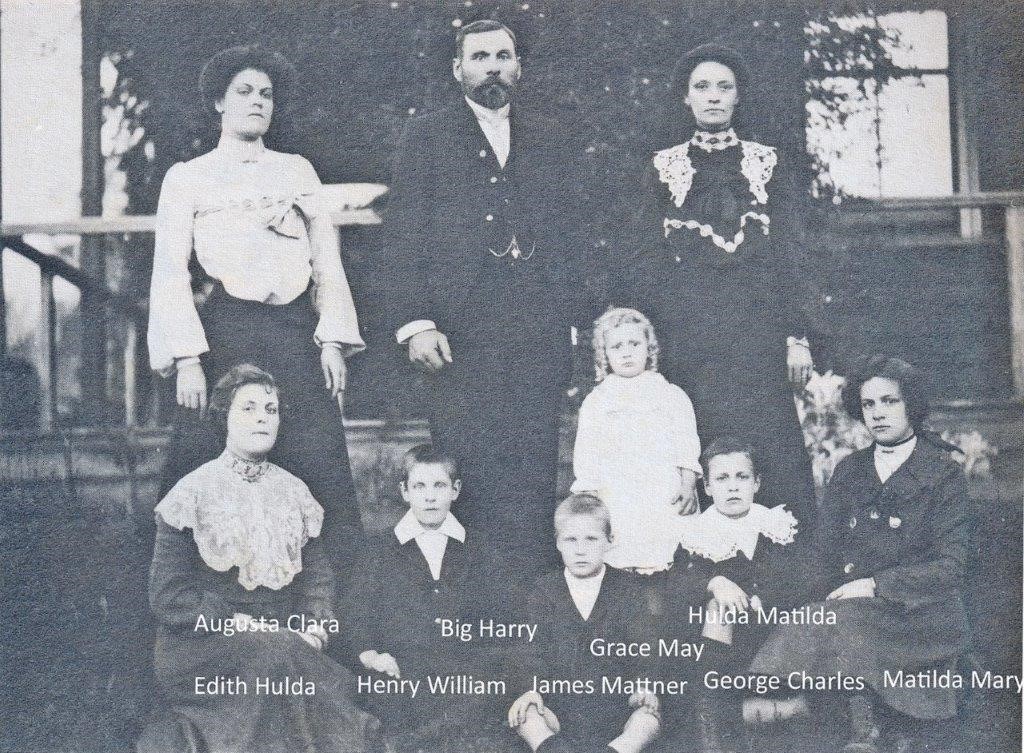

The Smith family c1902

Harry Smith’s Career

Harry Smith obtained work on a timber mill in the Balhannah Forest, only a couple of miles from Oakbank in the Adelaide Hills where the Mattners had a blacksmith and wheelwright business. The forest was cut out and no longer exists. Nothing more is known about his movements until he was head-hunted by the Millar Bros. on the advice of a Mr Munro, who saw him working as a big benchman in a mill somewhere, believed to be Naracoorte, SA.

Millar Bros. obtained the contract from the W.A. Government to supply the sleepers and bridge material for the completion of the railway line from Beverley (130 kms east of Perth) to Albany (380 kms south of Beverley). They were harbour contractors in Melbourne. They moved to Albany, bringing 200 men including Harry Smith and began building two mills at Torbay (half-way between Albany and Denmark) in 1884. These operated for approximately two years, by which time the railway line was complete. They dismantled the mills and stored the machinery at Albany.

In 1889 timber was again required to fill a contract with the Melbourne Harbour Trust Commission for wharf construction and Millars and a whole crew again came to Torbay and built two more mills, further west from the first two. These mills were both built by Big Smith. When the district timber was ‘cut out’ they moved to the Denmark River further west and established four more mills. That site became a town and is now a very popular tourist town. Big Harry constructed these mills and worked his way up to the position of manager.

When the area was nearing its ‘cut out’ stage, Millars asked Big Harry to travel up to jarrah country. The trees they had handled at Torbay and Denmark were mostly karri and a few jarrah.

He was impressed by what he saw and Millars decided to build the Waigerup Mill (the original name for Yarloop). Big Harry built that mill in 1895 and later another mill known as Waterous, up in the Darling Range east of Yarloop.[3] Another mill known as the Klondyke was also erected nearby but we have no record of him as the builder.[4] All these mills included railway tracks in the bush as well as into the main Government lines.

At this stage, Millars decided to erect a large mill and townsite up in the hills south of Yarloop. The site chosen became known as Mornington. Thus in 1898 Harry began building the first of two mills, one behind the other, which became the largest timber mill station of its day. It was certainly Millars’ biggest mill and they became the biggest saw millers in the world, operating as Millars’ Timber and Trading Co Ltd. They also owned the biggest privately owned railway system in the world.

After Harry’s death, Hulda moved from Mornington Mills and lived with her son Jim and his wife Isobelle at Wokalup, not far from the hills where she had lived so long. Hulda died there on 23 September 1937.

Some later reflections on Big Harry at Mornington

Big Harry was his own boss. He expected everyone to do a good day’s work, and soon sacked anyone who didn’t meet his high standards. No grog was allowed on Millars’ mill sites. If Harry heard on the grapevine that one of the workers was spending his wages on grog or horses and neglecting his family, he called him into the office and made it quite clear that this had to stop or he would be fired. It was said that a second offence resulted in a punch in the jaw and on the third offence the worker was fired. The man’s wife and family were allowed to stay on in the mill and have food, etc., supplied to her until the husband obtained a new job and collected her and family.

Harry was aware that some of the men travelled to Wokalup on the evening timber train and that they returned with bottles of alcohol, so he occasionally met the train on its return and collected the bottles and broke them on the railway track in front of the owners.

He was the first mill manager to supply running water for the mill houses and at a later date he provided electricity to the houses once the mill was connected.[5]

Harry Smith was instrumental in having a school at Mornington – (See ‘Mornington Mill State School’ on this website.)

When the Mornington Hall was asked for, he had it built and included a specially sprung floor for dancing –

He built a hospital, one of the first mills to have one, and the staff were on the mill pay sheets. [Other mills had hospitals built earlier in their history than Mornington, see ‘Mornington District Hospital 1909 – 1953’ on this website. Ed.]

In some of the reunion days that have occurred, many old people have told me that whenever he was travelling to Harvey or Bunbury in the early days, he would allow several of the young girls to go with him shopping in his horse and sulky, and in later days in his car, which was nearly always a Studebaker.

Harry had no mechanical training, but there were many machines that he designed and had built in the mill workshops. Nor did he have any training in surveying, but he carried out all the surveys for the rail tramways through the bush. This meant having the correct grades and curves, and he was able to do this in spite of no training.

Even though he was a hard man to work for, he was fair and just, according to the old people I have since met who worked at Mornington.

A final comment by Charles Craig, Millars’ Superintendent, who told my father in later years that he always dreaded his quarterly visits to Mornington, being too frightened to give Big Harry instructions on any change he might like implemented, because Big Harry always did it his way and that was that.

Overseas Travel and the Greek Timber Mill at Naoussa (now Naousa)

During the First World War the British Government didn’t use up their own forests to supply the necessary timber for the war effort, but imported timber from other countries. One of those countries was Greece and because their methods there were obsolete, the British Government wrote to Millars’ in Perth, asking if they could supply a man skilled in the timber industry who could go to Greece and smarten up their industry. After the exchange of several letters, Big Harry was selected for the job. The British Government paid his fare and wages to spend two years in Greece, mainly in Salonika, to modernise the industry. We have some photos of some of these activities in the snow. He rebuilt their mill in Naousa about 100 kms west of Salonica and put a tiled roof on it. It appears tiles were more readily available than iron in Greece.[6]

Harry Smith is in the centre.

Harry Smith is in the centre.

When he left Greece, Harry asked the British Government to arrange for my father, George Charles Smith, who was a soldier in France, to be given leave to meet him in Paris. This was agreed. However my father George was wounded several days before and couldn’t keep the appointment. Father and son did however meet in the hospital in Stourbridge near Birmingham.

Big Harry was asked by Millars’, whose head office then was in London, to continue his trip to the U.S.A., Canada and the Philippines, to look at their timber industries. Before leaving Chicago he met his sister, Augusta, who had been living in San Francisco for some years. She journeyed by train and they began their return trip and stopped off at Postville in Iowa where they met his brother and all the other members of his family who had migrated to USA from Norway. Harry arrived there in May 1918 and had a good family reunion. Since then three of them have been to visit us and spent a week with us and we have visited them. Family members are spread over a fair bit of Iowa but Elgin is the central town. We met many family members and saw many cemeteries where members of the older generation are buried. This is how we have been able to acquire the Norwegian family tree and they were thrilled to fill in the blank space that existed in the Australian part of the tree. Incidentally, his sister from San Francisco came to stay with the Smiths in Mornington, sometime between the 1920s and ‘30s.

At a later stage Millars’ again sent him around the world to look at machines, saws, etc., to obtain new ideas. We believe that this time his trip included Japan.

I should have mentioned that one of the conditions necessary for his trip to Greece was that the person chosen had to have knowledge of European languages. He obviously knew the Scandinavian language. Grandma Smith was German and his seafaring days must have given him some knowledge of some of the others.

Morgan Smith, grandson.

…………………………………………….

Harry Smith on the right, outside the office at Naoussa.

The following letter was published in 1917 in the South Western Times:

Letters from the Front.

The following is a copy of a letter Mr. W. Balston has received from Mr. Harry Smith, who, as our readers will recollect, was formerly manager for Millars’ Timber and Trading Co., Ltd., at Mornington: —

Naoussa Mills,

via Salonica,

Macedonia,

March 5th, 1917.

Your letter of the 22nd December reached me on the 25th February, so you will see that it takes a long time to reach one in this part of the world. It was very good of you to write and let me know how things are in W.A., and to wonder if I reached Salonica safely.

The “Morea” is a very good boat to travel by, and we had very fine weather right through, though a bit warm at Colombo and Aden. We heard at Aden of the “Arabia” disaster in the Mediterranean, which made us rather anxious for the rest of the voyage, and after leaving Port Said we had to have life belts at our side all the time until we got to Marseilles. I left the boat there and got the train to Boulogne, arriving in London on the 20th November.

I had five weeks in London, during which time our London office was trying to secure for me a passage to Salonica by transport of mail boat from Marseilles, but could do neither. I did not worry very much, as I thought there were plenty of worse places than London to spend Christmas in, despite the fact that it was in darkness at night, and sometimes all day as well, from the continuous fogs and smoke, which made it so dark that traffic had to be stopped for a day or two at a time. I think I saw London at the worst time of the year. The directors were very nice, and did all they could to give me a good time of it whilst in London, so I had a fairly good time, but as I had the worst part of the journey before me, I did not feel much inclined to go out.

Ultimately I left London on the 27th December, in company with a Mr. Campbell, who is the company’s agent in Salonica. We went to Paris in the hope of getting a French mail boat from Marseilles, but this could not be done; so we took the train for Rome and Naples, where we got an Italian steamer for Salonica. This was a very interesting trip through beautiful scenery, but it is no fun travelling in Europe at the present time, as one has to get their passports examined and filled in at every town one goes through. Luckily, Mr. Campbell could speak all the languages required as we went along, which was a great help. The Italian steamer was a small boat of about 1,000 tons, and it took six days from Naples to Salonica. We had three distinct warnings of submarines on the way, but luckily did not see any, and were glad when we got to Salonica, where we arrived on the 8th January.

The mills are 50 miles by rail and 12 miles by road from Salonica towards Monastir, and we reached them on the 13th.They are situated on the side of a great mountain, which overlooks the plains of the Vardar, and there is a great view. The forest is in the mountains back from the mills, and they are very steep, being as much as 9,000 to 10,000 feet high. They have been and still are the homes of the brigands. We have to keep five men with rifles guarding the mill night and day, these men being paid by the company. Some of these men have been brigands, but are now alright. There are also six Government police stationed at the mill. Most of the men working here live in the villages back from the mills, and when they go home once a month they have to have a police escort to their homes, as they have been frequently robbed, so you will see that this is not the best place in the world to live in.

The timber here is beech, and the trees are very small, the principal cutting being sleepers. Some of the logs are so small that they only make one sleeper. The logs are brought to the line by manual labor, there being no horses or bullocks for log hauling. The sawn timber is carried to the main line by an overhead ropeway on trestles, which works by gravitation. The timber is carried on small hangers taking four sleepers each, the load going down on one side and the empties returning on the other. As the mill is 4,500 feet above the railway, this works fairly well. We can hear the guns night and day, but must not refer to military matters. (South Western Times, 8 May 1917, p. 3)

………………………………………………………

[1] Norway Church Records 1812-1938, Birth, Baptism and Christening, per Ancestry.

[2] Norway, Select Census 1875, FHL Film No. 255578, per Ancestry.

[3] Waterous Mill was opened in 1897. Adrian Gunzburg and Jeff Austin, Rails Through The Bush, Rail Heritage WA, Bassendean WA, 2008, p. 51.

[4] Klondyke operated between 1899 and early 1900. Rails Through The Bush, p. 51.

[5] Mornington Mills, Murdoch University Studies in Industrial Archaeology 1. A record of an industrial Archaeological ‘dig’ at Mornington Mills May 1980, undertaken by the Murdoch University Programme. Edited by Margaret Hamilton, Series Editor Dr R Pascoe, p. 21.

1904 – more homes built, no piped water.

1920 pan system, one cold tap to some houses. Wood stoves, no bathrooms.

1938-39 – some outside wash houses built for coppers.

1940s still only one cold water tap to some, not all, houses and galvanised baths. Some kerosene refrigerators. Kerosene lamps.

1958/9 electricity to town, only to a few homes.

[6] Naoussa Mills, via Salonica, Macedonia, – see South Western Times, 8 May 1917, p. 3, below.